In Oregon’s cannabis industry, nearly every day brings a new lawsuit for unpaid bills, a new lien for unpaid taxes, and another company thinking about giving up.

At the root of the industry’s problems: oversupply. Too much weed sold by too many retailers means lower prices, which means producers, processors and even middlemen lose money.

State economists track the industry closely, in part because quarterly cannabis tax payments fund the drug treatment services created by Measure 110.

For most of 2023, a downward trend in production promised an easing of the industry’s woes.

But state economists Mark McMullen and Josh Lehner’s most recent forecast, released Nov. 20, contained crushing news for the industry.

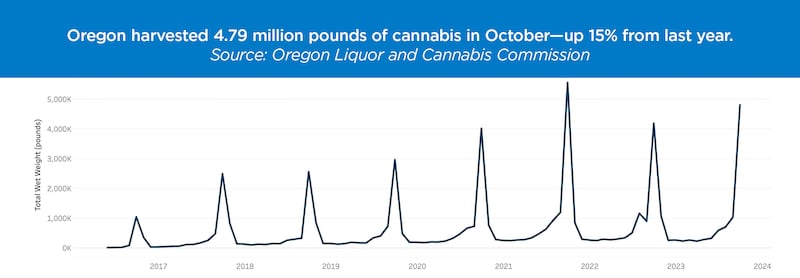

“Through the first nine months of the year, the marijuana harvest was nine percent lower than a year ago, and 15 percent lower than the record crop back in 2021,” the economists wrote. “As the market appeared to be adjusting, prices were stabilizing. That changed with the large October outdoor harvest which is 15 percent larger than last October.”

Beau Whitney, an independent Portland economist who tracks cannabis markets in Oregon and across the country, says the October supply spike “couldn’t have come at a worse time.”

In response to an industry survey Whitney is currently conducting, more than a third of respondents said they are struggling to pay taxes and even more said they are struggling to pay their debts. In many cases, retailers aren’t paying wholesalers who aren’t paying producers.

“People are walking away from cannabis licenses or selling them for pennies on the dollar,” Whitney says.

Across Oregon, cannabis tax delinquencies are up, and tax collections have fallen short of estimates in four of the past five quarters.

Those soft tax revenues are the reason weed struggles reverberate beyond the industry. Measure 110, Oregon’s drug-decriminalization experiment, hinges on about two-thirds of cannabis taxes (which produce a net of $150 million a year) going to addiction treatment services. So low prices and high delinquencies threaten Measure 110′s shaky underpinnings.

Whitney says if the state wanted to buoy prices, it could move to reduce the number of licensees or their capacity, as Colorado has done. But Mark Pettinger, a spokesman for the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission, says current conditions are the result of intentional policy decisions—and the federal government’s intransigence.

“The state and the industry and elected officials envisioned Oregon becoming a net exporter under federal legalization,” Pettinger says. “The oversupply we’re seeing underscores the dilemma in all states where marijuana is legal—it’s the equivalent of an Iowa corn farmer only being able to sell his crop within Iowa.”