Reed College occupies a lofty position in private higher education in Oregon.

It is by far the most selective four-year school in the state. It’s also the wealthiest. Records show that Reed boasts a greater endowment per student than University of Portland, Lewis & Clark College, Linfield University, Pacific University and Willamette University combined.

Notable Reedies include late Apple Computer co-founder Steve Jobs, musician Ry Cooder, Nickel and Dimed author Barbara Ehrenreich, a prodigious list of eminent scientists and academics, and 32 Rhodes scholars.

For all the accomplishments of its students and faculty, however, Reed has largely remained an island unto itself in Portland. Its verdant 103-acre campus in Eastmoreland might as well have a 10-foot wall around it, as separate as it is from the city.

A new novel, Need Blind Ambition, written by a former longtime Reed staffer, offers a rare look from inside Reed’s cloistered community.

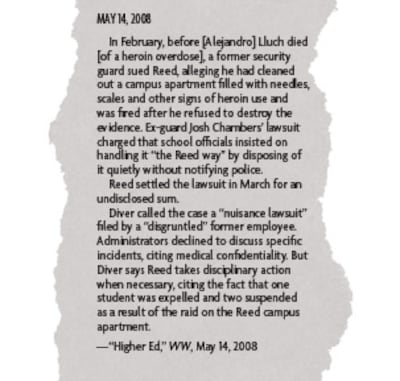

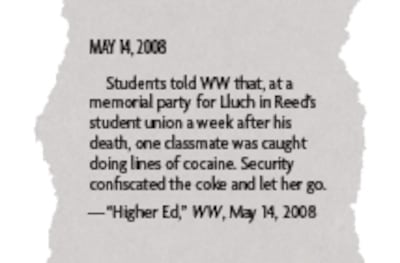

Small, elite and inward-looking, Reed rarely makes the news. But when the college endured sustained scrutiny from WW 15 years ago (“Higher Ed,” May 14, 2008), the topic—and the timing—could not have been worse. What started with reporter James Pitkin’s inquiry into a seemingly routine employment lawsuit turned into a firestorm that eventually led to the hiring of a lawman as Reed’s new president, not to mention years of animosity between Reedies and this newspaper.

The issues: the use of hard drugs on campus, the college’s culture of tolerance of the practice, and the fatal heroin overdoses of two students within less than two years.

The headlines coincided with the 100th anniversary of Reed’s founding in 1908 and fell in the midst of the college’s largest-ever capital campaign, a $200 million fundraising effort.

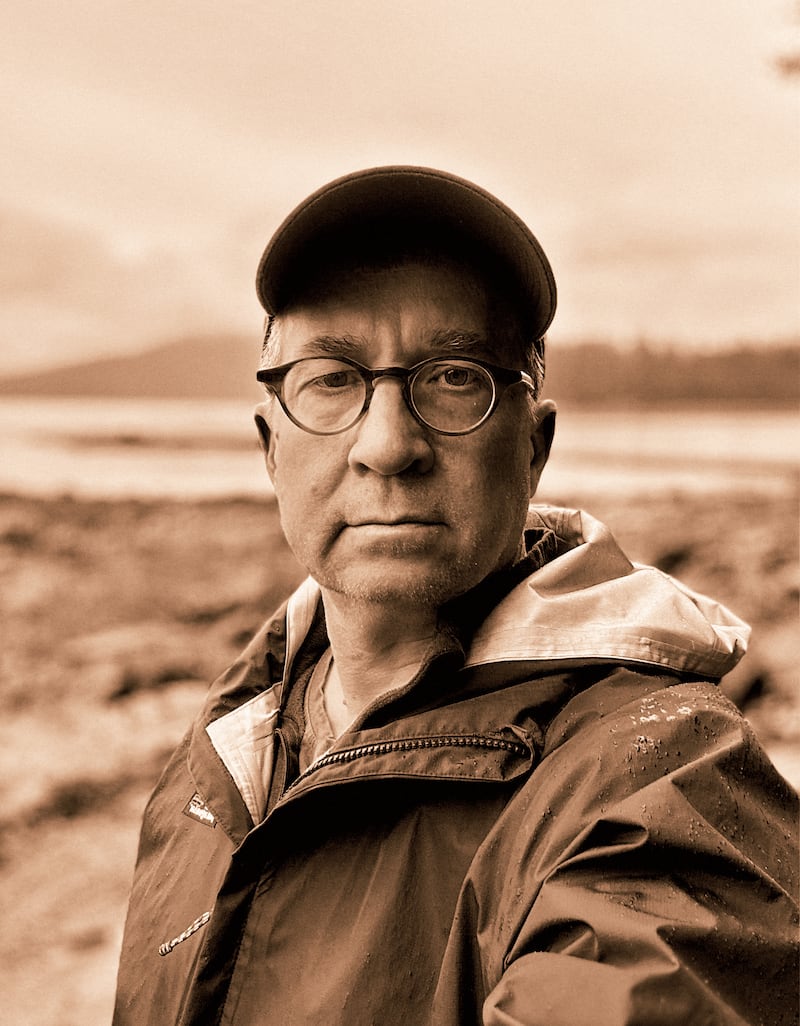

Author Kevin T. Myers, then Reed’s communications director, led the college’s damage control team during the years the fatal heroin overdoses occurred. With Need Blind Ambition, Myers brings that fraught period back to life from the perspective of a man who, in his day job, had told WW there was nothing to write about.

“When you’re the spokesperson—I don’t care if it’s for Reed College or Pepsi—every time you open your mouth, you feel like it could be your last day on the job,” Myers says now. “You always feel like you’re one stupid sentence away from the door.”

Myers, 56, left Reed in 2022 after 15 years there. He writes with the keen eye of a journalist, which he once was, and the sharp sense of humor of a standup comic, which he also used to be. The novel contains all the legal disclosures establishing that it’s fiction: “Any resemblance to actual persons living or dead…is entirely coincidental.”

But there sure are a lot of coincidences.

Like Myers, the novel’s main character, Peter Cook, arrives at an elite liberal arts institution in Portland from Alaska in 2007. (It’s called Parker College in the novel.) He works for a towering figure who, like then-Reed president Colin Diver, cut his teeth in Boston politics. Also like Diver, the fictional president pushes his college toward a “need-blind admissions” policy that would greatly expand its applicant pool. The book’s hard-charging prosecutor maps to then-Multnomah County drug chief Mark McDonnell. And the protagonist’s life is endlessly complicated by a dogged reporter from a scrappy newspaper called Stumptown Weekly. In one close echo of what really happened, Parker College officials encourage the parents of a student who fatally overdosed to revise and resubmit a letter to make it less critical of the college.

Need Blind Ambition is fiction, yes, but parts of it read like the truth shrouded in a veil thinner than a butterfly’s wing.

Justin Hocking, a writer who teaches creative nonfiction at Portland State University, says Need Blind Ambition fits into the literary tradition of the campus novel and perhaps even the subgenre “dark academia.” Hocking, who lived in Portland when Reed went through its challenging years, hasn’t read Myers’ book but says there are a variety of reasons authors might choose to fictionalize their experiences.

“Sometimes it’s settling a score or avoiding self-incrimination or possible legal action from an institution,” Hocking says. “In some cases, it’s a lot safer, and it’s a completely valid choice.”

Because Myers’ book adheres so closely to the story as it unfolded from 2008 through 2010, an attentive reader can’t help but notice when Cook, Parker College’s spokesman, discovers two troubling realities: that a shift to a “need-blind” admissions policy is actually a shrewd tactic that reduces the number of troubled rich kids Parker College admits; and that the college is shielding students whose drug habits break the law by hiding them behind federal medical privacy protections.

The first is an arguably harmless hypocrisy: dressing up a self-interested practice in the rhetoric of equity. The second, however, is a ruthless effort to hide criminal acts from law enforcement and the public.

Sheena McFarland, a Reed spokeswoman, declined to address Myers’ book. “Our understanding is that this is a work of fiction, and we will not comment on fictionalized policies or their imagined intent,” McFarland says.

Related: Read an interview with Kevin T. Myers.

Excerpts from the book, interspersed with passages from WW’s reporting at the time, appear below.

We also spoke to Myers, who insisted that he created the novel from his imagination, informed by his contemporaneous journals, his knowledge of Reed’s administrative machinery, and a dash of headlines from other colleges.

You be the judge.

Excerpted from Need Blind Ambition. Copyright © 2023 by Kevin T. Myers. Excerpted by permission of Beaufort Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Like author Kevin Myers, the novel’s protagonist, Peter Cook, grew up in humble circumstances near Boston. He reveres the president of Parker College, Charles Loch, a lawyer and former politician from Boston.

Loch remained an outspoken champion of equitable causes through his transition into higher education. His first act as Parker College President was to launch a $250-million fundraising campaign to support need-blind admissions. In a mostly eloquent editorial published in the New York Times, Loch identified need-blind admission as a social imperative for the nation’s top schools. Evoking the egalitarian spirit of Parker’s founders, who imposed no restrictions on admission based on religion, race, or gender, Loch vowed to remove all restrictions to admission, including a student’s ability to pay. He argued it was vital to the survival of American democracy to abolish all hurdles to higher education for those who exhibit dedication to scholarship, discovery, and independence of thought but lacked the wherewithal to attend the country’s great institutions.

In true Loch form, the last third of his piece descended from eloquence into a barroom brawl. He took a few well-deserved jabs at elite schools who fudged their financial aid data to call themselves need-blind as a marketing ploy to attract more applicants. He went on to characterize many state colleges as minor league sports complexes with second-rate academic programs, referring to one of Oregon’s most beloved public institutions as “a football team with an educational annex.”

Peter arrives on campus in the midst of a public relations crisis: The college faces a lawsuit from a security officer alleging he was fired for refusing to cover up a student’s drug dealing.

“The college is being sued.” Loch dove right in. “A former security guard is saying we covered up a drug operation in the dorms and is accusing us of forcing him out for not colluding in our coverup. Peter, what questions do you have?” Loch waited.

Loch’s directness could make people feel uneasy. It made Peter trust him. “Is there any truth to the allegations?” Peter’s nerves caused his intensity to be a bit high and put too fine a point on his question.

“That is the obvious question, isn’t it? Funny you’re the first to ask,” Loch nodded his approval to Peter. “No. The whole thing is manufactured. He wasn’t even fired. The allegations are outrageous, drugs and copious paraphernalia, blood and gore. I can’t imagine the absurdity of the claims is going to matter much, however, to certain press outlets.”

Loch asked, “How will this be covered by the press?”

“They’ll report on the allegations, just as his lawyer assumes they will,” said Peter. “They’ll be careful not to call them facts, but they’ll also be careful to choose the most eye-popping charges.”

“Which is why the suit reads like a ‘50s crime novel.” Loch continued, picking up the complaint and reading aloud. “’He told me to clean the blood from the walls and kitchen floor. I asked him if we were going to call the cops. He turned to me slowly and said, and I’m reading verbatim now, ‘around here, we take care of things ourselves. That’s the Parker College way.’ So, Peter, did you know you were coming to work in a Mickey Spillane novel?”

Beset by panic attacks and thrust into office politics, Peter makes a drinks date in the Pearl District with a predecessor, Rhea Smith—who was fired when she refused to take part in a coverup. There, he learns there is another reason for the college president’s emphasis on need-blind admissions.

Rhea was sipping her drink and had to catch herself from spitting it out. She wiped her mouth and chuckled. “Yeah, I forgot you had a crush on Doc Loch.”

“He was the last of the liberal lions of Boston politics!” Peter laughed at his defense of Loch. “The guy’s a legend.”

“Sorry to kill your fantasy, my dear, but he’s an also-ran… for the fucking mayor of Boston. He’s irrelevant. The man is the answer to a trivia question that nobody’s asking,” said Rhea with a chuckle, “and you’re the only one who’d know the answer anyway.”

“You’re brutal,” Peter joked. “The Need-Blind op-ed was a gamechanger.”

She smiled at his naïveté and took a deep breath before jabbing another pin in Peter’s Loch bubble. She gave him the inside scoop as to why need-blind admissions became a top priority for the college. The Board of Regents hired Loch with the directive of moving the college’s reputation from a drug-friendly safe haven where rich kids came to cosplay at counterculture shenanigans, to something near the mainstream. Loch had the institutional research department see which students were committing the acts that were deemed reputational threats. The study found that over 90 percent of the disciplinary actions, medical leaves, and suspensions came from rich kids who had been accepted off the waitlist. It was determined they needed to broaden the applicant pool—need-blind admissions and eliminating the application fee were the ways to do that. Since Peter was in his first job in higher ed, she gave him an overview of the admission process.

Super-simplified college admissions: to enroll a class of 300 freshmen, the college needs to accept 1,500 applicants, knowing that roughly 1,200 of those students will enroll at other colleges. That’s the easy math. There is not enough financial aid for all 300 students. Some get a free ride, and everyone else pays somewhere between a little bit and full price. This is where the calculus gets more complex, but it’s easy to see how the process favors the rich. The kids who can pay full price, have good grades, and have clean records all get in—all of them. A dozen or so of the poorest kids with perfect GPAs, no blips or blemishes on their records, and outstanding extracurriculars also get in—and everybody feels good about that. The poor kids with hiccups on their records, like a B-plus in calculus, get put on the waitlist with all the dumb, rich troublemakers. At the end of the process, when all the financial aid has been distributed but there are still seats to fill, the college starts choosing students off the waitlist, based almost solely on their ability to pay full tuition. For those last ten-to-fifteen spots, money trumps piss-poor GPAs, trumps lethargy in extracurricular life, and, for a few very wealthy applicants—money even trumps criminal behavior or failed attempts at rehab, or both.

“That last cohort of kids makes up about five percent of the entire student body, but it comprises over ninety percent of disciplinary actions, medical leaves, and suspensions,” Rhea explained. “From a marketing standpoint, schools with need-blind admissions attract a lot more applicants. Bigger pools mean more choice of students across the socioeconomic spectrum, which means you can stretch your financial aid further, which means having to admit fewer rich delinquents. Loch saw need-blind admissions as the best way to eradicate the troublemaker waitlist, full-pay students who were causing all the reputational issues. In Parker College admission jargon, they’re WFPs, Waitlist Full-Pays, or as some call them WTFPs—What the Fuck, Parker?”

“You said medical leaves? I assume that’s code for rehab?” asked Peter.

“What’s the Stumptown angle?” she asked, ignoring Peter’s question.

“He seems to be talking to an assistant DA who doesn’t think we call the police when we should,” said Peter.

“You should start looking for another job, now. Seriously,” said Rhea as she took a long pull from her gin. “I’m not sure how much more I should say.”

“Just tell me about medical leave,” said Peter.

“You heard none of this from me. Right?” Peter nodded.

“Okay, so you know about HIPAA [the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act], right? It’s intended to prevent the sharing, or selling, of medical information for its use against patients, blah, blah, blah. It makes it illegal for an institution to talk about people’s medical issues. So, the richest, most well-connected kids who are, let’s say, selling drugs on campus, mysteriously take ill and go on medical leave. Sometimes it’s forced by the administration, and sometimes it happens after a talk with Mommy and Daddy or their lawyer.”

“But always before the police are called.” A light came on that dimmed Peter’s idealism.

“No comment,” said Rhea.

“So, a disciplinary issue, or, as they call them in some circles, a felony, becomes a confidential medical issue, and then the student transfers to Hampshire College?” intuited Peter.

“It all depends on how well connected or rich Mommy and Daddy are,” said Rhea.

“I thought FERPA [the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act] protected all that information, anyway.”

“It does, and it doesn’t,” explained Rhea. “FERPA allows Rosen, or Rosen’s successor, to tell an employer, or another college, anything they deem important for them to know; under HIPAA, nothing can be legally disclosed, ever, by anyone.”

Soon, matters get worse. A student suffers a fatal overdose, and Parker College’s senior administration discusses damage control. College officials—President Loch, Vice President of Student Affairs Matthew Rosen, and VP of Advancement Alistair Goodwin—try to decide whether to shoulder some responsibility or blame the student.

The parents knew about Josh’s drug problem. His father said he went to bed every night fearing, dreading, anticipating the night when the police would come knocking with tragic news. After the parents learned of the uptick in overdoses near campus, they agreed to share the cause of death to spare another family from going through the same pain. They were unwilling, however, to publicly share Josh’s history of use. Not disclosing that Josh died while relapsing, they understood, would make everyone assume his heroin habit was acquired at Parker. Putting on his clinician’s hat, Rosen shared that Josh’s parents believed he had been clean, which fits with the profile. Overdoses are common during relapse. Addicts default to their previous dose, but their tolerance is diminished. Rosen looked like he was trying to read the room. “I think that could also be a lifesaving message that would be very useful to share.”

There was an awkward balance while walking the tightrope between the institution’s reputation and the legacy of a nineteen-year-old. The knee-jerk impulse of the top brass was always to protect the college—to defend the status quo. At the most basic level, the group was about to choose between acting in accordance with the credo professed in their founding documents or acting to protect their brand and their position in the college-ranking magazines. During times of crisis, people show their true nature, Peter believed, and he yearned for Loch to make the right choice. It felt like watching the wheel of fate.

“I don’t see why we can’t just share whatever we think is in the best interest of the college,” said Goodwin. There was a weighty pause.

Loch pondered aloud if HIPPA and FERPA were still enforceable after a student dies, before suggesting it was probably in the college’s best interest to observe the parents’ wishes.

Peter agreed it was wise to follow the parents’ desire. He didn’t care how they got to the right decision, he just wanted to be on the right path. To reinforce Loch’s direction, Peter moved the conversation to the next decision.

“My experience as a reporter, when covering untimely deaths… Well, let me just say, there is a marked difference before and after family members see the deceased. First comes denial and then comes anger and bargaining. It would be good if the parents spoke with reporters before they got to Portland, or at least before they got to the morgue, if possible.”

GO: Kevin T. Myers reads from Need Blind Ambition at Annie Bloom’s Books, 7834 SW Capitol Highway, 503-246-0053, annieblooms.com. 7 pm Thursday, Feb. 22. Free.