The Oregon Public Employee Retirement System issued its annual report this week, a holiday gift for people who like numbers and want to understand an arcane but important component of the state’s finances.

PERS now includes a record 405,373 members, a number equivalent to nearly 1 in 10 Oregonians. Of PERS members, slightly fewer than half are still actively employed in Oregon government jobs. The rest are either retired or inactive, meaning they are neither retired nor working for an Oregon government employer.

Although the gold-plated pensions paid to former Oregon Ducks football coach Mike Bellotti and a slew of high flyers from Oregon Health & Science University have regularly captured headlines, the median annual payout for PERS retirees in 2022 was $27,156.

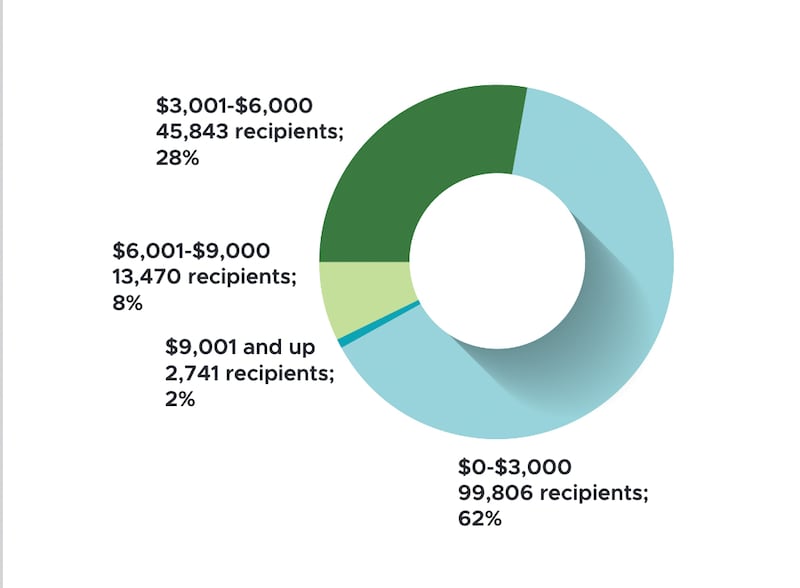

Here’s the distribution of monthly payouts for the 161,860 members who received a PERS pension in 2022:

The PERS system has been a political lightning rod for years for at least three related reasons:

1. Lawmakers made overly generous benefit decisions in the 1980s and ’90s.

2. That generosity led to a large unfunded liability—i.e., the system owed more to future retirees than it could pay.

3. The unfunded liability meant that employers had to contribute ever-larger portions of their operating budgets to retirement benefits, which had the effect of reducing current services.

The new report sheds some light on all of those issues.

First, controversial legislation that reduced benefits for workers hired after 2003 changed the system significantly. As the older workers, called “Tier 1″ employees, age out of the system and die, the financial picture for the state improves. One example in the report: In 2002, at the height of the impact of generous benefits lawmakers approved, 17.4 % of retirees got an annual pension that exceeded their highest annual salary while working. In 2022, that percentage shrank to 0.7%.

Most of the PERS payouts come from a large pool of investments that fluctuate with the stock market. In 2022, stocks had a bad year, so the investment portfolio declined, which in turn increased the unfunded liability. (Good news: The stock market roared back in 2023, which will reduce the liability.)

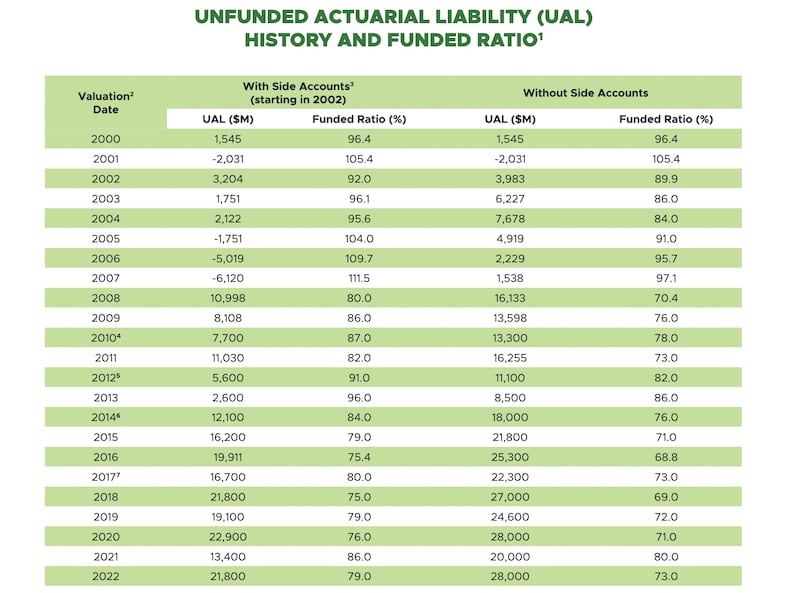

Here’s how the unfunded liability, which stood at $28 billion at the end of 2022, has changed over time (that liability, including supplemental “side account” investments, is now less, $21.8 billion):

This chart shows how employer contributions (as a percentage of payroll) have risen over time. (There are two different rates: one for employers who set money aside in “side accounts” to increase investment earnings, and another rate for employers who did not.)

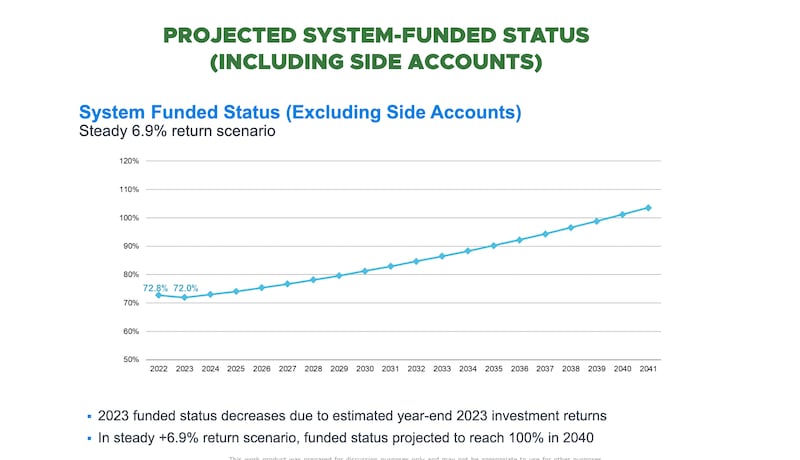

The report also includes a projection of when the unfunded liability will disappear—if the PERS investment portfolio earns steady returns of 6.9%. Here’s what that scenario looks like:

In a preface to this year’s report, PERS director Kevin Olineck noted that benefit reductions for new public employees that then-Gov. Ted Kulongoski pushed 20 years ago put the system on a sustainable path.

Those choices angered public employee unions and effectively ended the careers of at least two Democratic lawmakers, former state Rep. Greg Macpherson (D-Lake Oswego) and state Sen. Tony Corcoran (D-Cottage Grove), but saved the state from fiscal ruin.

“The pension reforms initiated in 2003 are paying off over the long run,” Olineck wrote.