Paul Watts parked his Ford F-250 along Southeast Stark Street beside Interstate 5 and looked at an alphabet soup of graffiti signatures on the concrete walls and Jersey barriers.

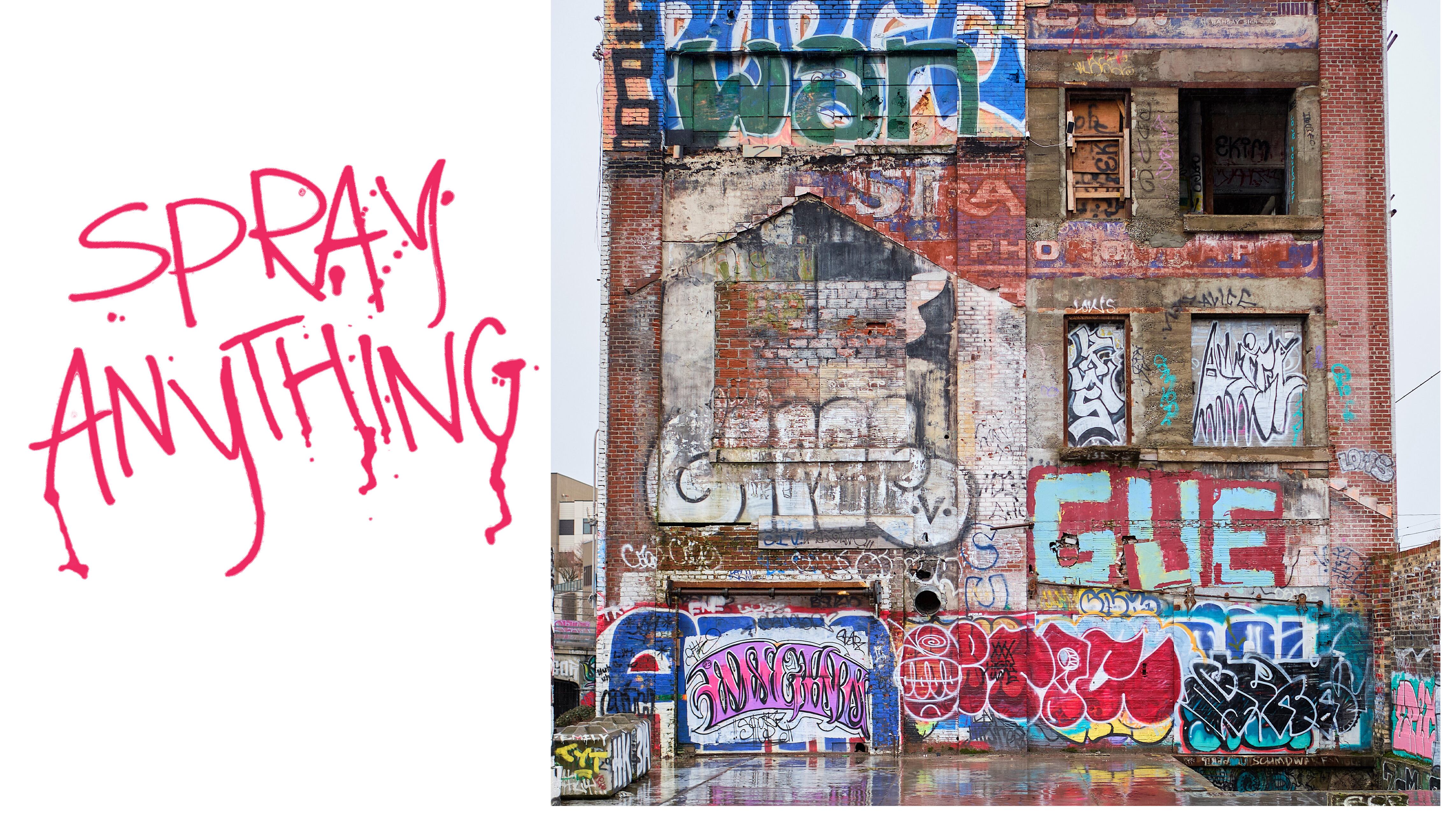

There were large “throw-ups”—words painted in bubble letters: SYLSNM. OMEGA. BAMBI. DRAIZ. There were many more quick tags: SARSEX. TERP. HOBOS. CESAR.

Watts, 55, an imposing man who looks like Bruce Willis in his prime, runs Graffiti Removal Services, a 25-employee company that’s been in business for 20 years.

He recognized some of the tags—spray-painted nicknames that let the world know someone braved the traffic and the cops to make a mark. Not many, though, because so few are done by locals. Most are probably done by taggers who drive up and down I-5 between Los Angeles and Seattle, Watts says, couch surfing with friends and writing on any surface they can find.

No matter the source, Watts says he could spray over the graffiti on the Jersey barrier in about 15 minutes. The other stuff, between the lanes on I-5, would take a little longer.

He said the same thing over and over on a 90-minute drive around town, eyeing low-hanging (and out-of-reach) graffiti on buildings, sidewalks, construction sites, parking meters and mailboxes.

There was a whopper on the Morrison Bridge flyover at 2nd Avenue: huge, sloppy red figures along the top floor of a building. This was a “fire extinguisher tag,” Watts explained. Taggers drain the retardant out of a fire extinguisher, fill it with diluted paint, pump it up with air at a gas station, and wield it like a paint flamethrower.

Removing or covering graffiti quickly and consistently is the only thing that deters taggers, Watts says. “Once you take your foot off the gas, you’re screwed.”

To be sure, it behooves Watts to argue for more graffiti cleanup money because he gets paid to remove the stuff. But he has plenty of private clients and isn’t hurting for work. And experts agree that removing graffiti, or painting over it quickly, deters taggers from coming back.

So why aren’t the city and the state doing more of that?

The answer is a laundry list of the gremlins that have bedeviled local elected officials for the whole of this decade: a short attention span, a form of city government that balkanizes responsibility for removal, and a leadership vacuum as deep as Sullivan’s Gulch. And that was before inflation and a shrinking gas tax hit the Oregon Department of Transportation, which bears responsibility for detagging hundreds of miles of roads. Portland’s Bureau of Transportation ran out of money, too.

The result is a city now covered in spray paint, indelible marker, and “mops”—squeezable cylinders full of ink. (“The perfect marker you can always keep in your pocket, handy, easy to conceal,” according to online store Bombing Science.)

So how did we get here, and what can be done? We jotted down those questions, and a few others, then took to the streets and the phone to answer them.

Is graffiti in Portland worse now that it ever has been?

Probably. The city’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability says it received 5,260 complaints about graffiti in 2022, more than double the 2,117 the city got in 2021 and almost six times 2020′s 897. Through May 2023, the latest month for which there is data (because of a software switch), the city got 2,192 complaints.

Ted Miller, head of maintenance for the Oregon Department of Transportation’s Region 1 (most of the tri-county region and Hood River County), says tagging is through the roof since COVID.

“We’ve always painted out graffiti, but we’ve always been able to do it with a crew of two people in a truck,” Miller says. “Once COVID hit, a switch turned on, and it just exploded.”

Watts agrees. Worse yet, graffiti ethics are breaking down. Before the pandemic, taggers rarely defaced street art murals, which offered a defense.

“There’s no code anymore,” Watts says. “They are tagging murals like crazy.”

Who’s doing the tagging?

The consensus among people WW asked was that they are young white guys. A fact sheet from the city of Houston says “suburban males, pre-teen to early 20s, commit approximately 50% of graffiti vandalism” seeking “fame, rebellion, self-expression and power.”

One former Portland tagger, who declined to be named, said he started painting walls in high school for some of the same reasons kids pick up many hobbies.

“It provides the same thing as sports or music,” he says. “There is team spirit and ways to excel.” And it felt exclusive because “most people can’t even read it.”

Taggers are also thrill seekers, Watts the graffiti remover, says. He can tell from where he’s had to work: on the sides of buildings that can only be reached with ropes, on the undersides of bridges, and in the narrow medians of interstate highways.

A rare, high-profile arrest in Portland supports Houston’s demographic claims and the thrill seeking.

Emile Laurent, 22 at the time, turned himself in in August 2022 after Portland police issued a warrant for his arrest, alleging he caused $10,000 in damage by writing his tag, TENDO, on at least 14 buildings. Mug shots of Laurent match the Emile in a YouTube video who launches himself out of a tree on a skateboard (and sticks the landing!).

Police called Laurent a “prolific graffiti vandal.”

It hasn’t hurt his skate career. He still appears on the website for Swedish apparel firm Polar Skate Co., and, in March, he made the cover of Thrasher magazine.

Is graffiti a crime?

Yes. Laurent was charged with felony criminal mischief after police arrested him fleeing the Oregon Leather Company in Old Town, which he had just tagged.

Prosecutors stacked up more charges against him, making the penalties more severe, by laboriously identifying his tag all over town. In the end, Laurent pleaded guilty to one felony count and three misdemeanors. He was sentenced to three years’ probation, 100 hours of community service, and $6,815 in restitution to his victims.

The problem is that few taggers are ever caught in Portland. Until 2015, the Portland Police Bureau had a unit that focused on graffiti, Watts says. He remembers painting a wall for the cops, who would rig it with motion-sensing cameras and wait. When a tagger showed up, they’d make an arrest.

“Due to staffing issues, the bureau was forced to reduce its Graffiti Unit from two officers down to one and eventually eliminate the entire unit in December 2015,” the Police Bureau said in its 2015-16 annual report. “Prior to the elimination, the unit was able to arrest many prolific graffiti artists.”

Leaving graffiti on your building for more than 10 days is also a violation of city code. If forced to remove it, the city may charge the property owner for the service, plus an overhead fee of 25% and a civil penalty of $250 for each abatement.

But, clearly, the code isn’t being enforced. Graffiti stays on buildings for months. Need proof? Drive by the old Gordon’s Fireplace building on Northeast Broadway.

Sale of spray paint is also restricted by city code. Cans must be kept in locked cabinets or in storerooms, and records of sales must be kept for two years. Businesses that violate the code can be fined up to $5,000.

But there are plenty of places to buy spray paint, markers and mops online, including Bombing Science (“bombing” means hitting as many surfaces as possible in a given area). WW bought a Clockwork Orange (the color) graffiti mop for $6.95, no questions asked (we were tempted by Death Black).

“These restrictions only created inconvenience for the homeowner,” Watts says. “The taggers aren’t buying spray cans. They’re stealing them or finding ways to get them online.”

Who’s in charge of removing graffiti?

It depends on where the graffiti is.

Property owners are responsible for their own buildings. ODOT is responsible for state and federal highways. The Portland Bureau of Transportation cleans local streets. Multnomah County owns the bridges. The city handles city property, and the railroads (rich targets) handle theirs.

The various jurisdictions form a patchwork that can be difficult to navigate. Watts, for one, would like to tackle whole blocks at a time, removing and painting over graffiti on any surface he can. But even during a big cleanup in 2022, he couldn’t tackle parking meters or city road signs because city code requires union employees of PBOT to do that work.

The bureau says it uses in-house employees because, if cleaned improperly, signs lose their reflectivity, becoming unreadable at night.

Similarly, Miller at ODOT is working to clean up I-84 in Sullivan’s Gulch, where graffiti mars bridges, road signs, and just about any flat surface. The artery, one of the first things visitors see driving in from the airport, is a tangle of jurisdictions, including Union Pacific Railroad, a property owner that acts like a government unto itself.

So who dropped the ball?

In terms of city work, graffiti removal used to reside with the Office of Community & Civic Life, run by former City Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty. Civic Life took a softer approach to the problem. In an April 2021 press release, then-program coordinator Juliette Muracchioli said she was pleased to preserve Black Lives Matter tags and murals as Civic Life removed others.

“I am proud of the graffiti program’s work this past year,” Muracchioli said. “Not only have we proactively responded to graffiti complaints, but we have also been sensitive to the historic moment we are living in. During the height of the Black Lives Matter movement, the city permitted BLM-related messages and street art to remain on city assets.”

Hardesty didn’t return an email seeking comment.

Mayor Ted Wheeler tapped senior adviser Sam Adams to lead the anti-graffiti efforts. Before Adams was mayor, he worked for Vera Katz, who hated the stuff.

“Vera infected me with OCD about graffiti and utility pole posters,” Adams tells WW. “That infection has only grown over the years.”

Adams clashed with Hardesty over graffiti strategy. Adams wanted tougher penalties for defacing traffic safety signs, but Hardesty disagreed, Adams said. In October 2022, the mayor moved the graffiti program to the Bureau of Planning and Sustainability.

Months earlier, Wheeler had declared an emergency to create the Public Environment Management Office, or PEMO, and vested it with the authority to erase graffiti in the Central Business District. Staff at BPS collects complaints and does cleanup, but Wheeler’s PEMO acts as a sort of SEAL team, swooping in on trash and graffiti when conditions get really bad.

As part of the push, Adams engaged Watts, who says he went to work without a contract because time was of the essence. Watts and his team cataloged all the graffiti downtown and identified 23,345 tags.

Watts’ firm spent five months pressure washing, scrubbing and painting, and got that number down to 7,189.

And it would have stayed that way if the city had kept its foot on the gas. But shortly after the holidays, Portland downshifted, Watts says. Part of the problem: Wheeler and Adams parted ways in January 2023 amid complaints that Adams belittled staff, including graffiti leaders.

“After Sam left, we had no advocate,” Watts says.

Wheeler’s office says the mayor is still very much in the fight against taggers. Since July, BPS has spent $525,800 to remove 190,600 square feet of tags reported by Portlanders. It does so free of charge to small businesses, homeowners and nonprofits. And since PEMO’s inception, it and BPS have sponsored the removal of more than 300,000 square feet of graffiti.

“Mayor Wheeler takes the issue of graffiti in our community seriously and has spearheaded a number of initiatives meant to improve livability,” his office says.

But last year, the Oregon Department of Transportation ran out of money just when it needed it most. Pandemic-related inflation drove up the cost of road maintenance, leaving little for graffiti. As of now, ODOT’s Region 1 has just $210,000 for the two-year period that started July 1, 2023, down from $1 million the prior biennium (Oregon budgets run two years). ODOT is backing a bill in the Legislature that would allocate it another $4 million.

Worse yet, the Portland Bureau of Transportation in November exhausted $750,000 from the American Rescue Plan that it used to fund a four-member team that removed graffiti from 10,000 signs, 3,200 posts, 1,400 bike racks and 12 planter boxes. Since then, it has been doing only smaller projects with city funds, a spokeswoman says.

What can be done to deter graffiti?

This is a tough one. Taggers are determined and, often, ingenious.

A few made their way to the top of Jackson Tower on the south side of Pioneer Place and painted high-profile, bubble-lettered throw-ups there, likely by tossing a grappling hook and pulling down the ladder on the fire escape, Watts says. He and his team had to hire professional climbers to help them remove those tags (brick by brick because Jackson Tower is a historic landmark).

Filling blank spaces with murals used to work, but, as Watts says, they’re fair game now. And ODOT can’t put razor wire at the base of highway signs because it could injure someone.

Some cities have set up “free walls,” where taggers can tag to their heart’s content, legally. Watts says that’s a loser, too, because taggers often tag their way to and from the wall on surrounding structures, often trashing public transit.

Boston ivy can work as a deterrent, especially on highway sound walls, where ODOT lets it grow. The use of English ivy is off-limits because it’s an invasive species that takes over forests.

The best graffiti protection is public activity, like food carts, and better lighting, Adams says. Taggers want to put their work in high-traffic places where the greatest number of people will see it. To do that, they operate at night. During the pandemic, downtown buildings were sitting ducks because so few people were present, day or night, Adams says.

The unanimous consensus among experts is that fast, consistent removal is the best deterrent. Taggers move on if their work doesn’t endure, they say.

So, how do you clean off graffiti?

It depends on the surface.

Most paint-removal products contain acetone, alcohol or lacquer thinner. The problem is that Portland city code prohibits letting that cocktail of chemicals reach drains and the river. Water from pressure washers used to remove paint and cleaning solution must be collected. Watts, for one, carries expensive water collection systems on his trucks.

The other option is painting over tags. ODOT doesn’t do removal. It just covers tags and graffiti with “ODOT Gray” paint from Metro’s recycled paint program.

What about the graffiti on huge highway signs?

If you’re a taxpayer and you’re not pissed off yet, prepare to be.

During the pandemic, big, green federal highway signs became tagger trophies. Drive along Interstate 405 right now and you’ll see that someone has whited-out sections of signs directing drivers to Highway 26 and other exits. Other signs sport large tags.

The problem here is that these signs can’t be cleaned. Chemicals that remove paint also remove the coating that makes the signs reflective and visible at night.

That means they must be replaced. ODOT’s sign shop in Salem has to make a brand-new sign. When it’s ready, ODOT calls shipping companies and tells them that the road in question will be closed for a few hours in a month, because truckers use the roads at night. Crews go out with the sign and a big crane, close the highway or a couple of lanes at around 4 am, pull down the old sign, and put up the new one. They replaced a huge one over I-84 early on Jan. 28.

The price for all of this: as much as $8,000 per sign.

And there’s no guarantee taggers won’t hit it again. “We’ve found that they get around almost anything we do,” ODOT’s Miller says.

The highway department has begun putting a film on signs, like muralists do with wax on their work. The film works because it can be sprayed off, along with tags. But the treatment only works a couple of times, Miller says. Then it’s time for a new sign.

Isn’t Gov. Tina Kotek on the case here?

Yes. Kotek convened her Portland Central City Task Force last year to come up with solutions to the city’s blight, including graffiti. The PCCTF made recommendations in December, and Kotek said she would ask the Legislature for $20 million in ODOT funding for trash and graffiti.

The good news is, if it comes through, all the money would go to ODOT Region 1 (Portland and its environs). Miller says ODOT will use $4 million of the money for graffiti and $4 million for trash. For better or worse, he’s banking on it. He has fill-in-the-blank templates written and plans to put contracts out to bid as soon as Kotek signs the bill.

“We’re in the starting blocks,” Miller says. “We’re not waiting until the money comes.”

What about private money?

Tim Boyle, chief executive of Columbia Sportswear, is taking matters into his own hands. He’s donating $150,000 to clean up one of the worst stretches in Portland: I-405, from the Fremont Bridge to the east end of the tunnel on Highway 26.

Like many people in Portland, Boyle blames lax law enforcement for the graffiti problem.

“The cost of cleaning up graffiti that some of these people generate could be $100,000,” Boyle tells WW. “A graffiti-ist who’s doing that much damage should be put in jail.”

Eager to see taggers in orange jumpsuits, Boyle is among the biggest donors to criminal prosecutor Nathan Vasquez, who’s running against Mike Schmidt for Multnomah County district attorney. Boyle says cops told him Schmidt won’t throw the book at graffiti offenders.

Schmidt’s office says that’s not true. He studied graffiti cases from January through September and found that Portland police referred 17 of them to his office. Schmidt issued charges in 15 of those, or 88%.

“DA Schmidt knows that graffiti is a significant community concern,” spokeswoman Elizabeth Merah says. “Our office takes a hard stance on graffiti cases, and we pursue these cases aggressively.”

It’s not impossible to imagine that a CEO’s frustration with graffiti will indirectly lead to a new top prosecutor in Multnomah County. But Miller at ODOT hopes for another outcome: that the Boyle project will lead to others under the rubric “Sponsor a Highway.” It would be like “Adopt a Highway,” but instead of rallying volunteers to don orange vests and wield trash pickers, it would seek cash donations to clean up garbage and graffiti.

Washington state has a similar program that has shown results, Miller says. He hopes to get a pilot started with Boyle in March, when the rains stop and it’s easier to clean up graffiti (the rain complicates chemical removal and water capture).

By then, Miller hopes the Legislature will also have showered ODOT with millions in new funding. A guitarist and rabid Tom Petty fan (he has strings from Petty’s guitars in rings on his fingers), Miller, like his hero, won’t back down.

“With those dollar amounts, I see crews working seven days a week from 6 to 6,” Miller says. “I think we can make an improvement.”