The Oregon State Police investigation into Multnomah County jailers Mirzet Sacirovic, Jorge Troudt and Gustavo Valdovinos began in 2022, following a series of startling claims by former inmates.

Two years later, the results of that investigation are now public. But despite the evidence showing what the OSP investigator called a “pattern of misconduct,” prosecutors at the Multnomah County District Attorney’s Office declined to press charges. Here’s how the investigation came together—and why charges were ultimately dropped.

In 2022, as federal prosecutors prepared to take a racketeering case against a number of Hoover gang members in Portland, some of the Hoovers awaiting trial in the Multnomah County jail ratted out their guards. They alleged to FBI agents that deputies would do favors for them, including helping them attack their rivals, and suggested this had been going on for years.

Then-Multnomah County Sheriff Mike Reese says he first learned of the allegations in April after being notified by the FBI. His office launched an investigation. Six months later. he handed it over to the Oregon State Police and put Sacirovic, Troudt and Valdovinos on administrative leave.

The state police assigned a detective on its major crimes unit in Portland, Nicole Watson, to look into matters. Watson was a former corrections officer herself, having worked at the state women’s prison until being hired by the Oregon State Police in 2015.

During her six-month investigation, Watson learned how bad the conditions in the fifth-floor dorms had gotten.

She had some credible sources: deputies working on the units. One unidentified deputy said she witnessed an assault by a guard. Two deputies admitted to popping cell doors so inmates could fight.

One, Deputy Nathanael Lightner, told investigators that on Dec. 14, 2018, he popped open a cell door to facilitate a fight, calling it a momentary “lapse in judgment.” One of the Hoovers told investigators it was done at his request. (Lightner has since been removed from contact with inmates.)

Another deputy, now working in Utah, conceded that he’d done it once, in July 2019, and had “heard stories” about Valdovinos and Sacirovic doing it too.

On the other hand, the three deputies officially under investigation all denied misconduct. (Troudt and Sacirovic did so in interviews with investigators. Valdovinos requested a lawyer and didn’t speak.)

Other deputies said they didn’t see anything, or declined to speak altogether. In October 2022, shortly after OSP took over the investigation, the president of the deputies’ union, Matt Ingram, sent out a memo telling his colleagues not to speak to detectives. After Ingram retired in early 2023, his successor Nicole Buscher took to barging in on investigators’ interviews uninvited.

The investigation hit other snags. OSP investigators couldn’t locate many of the witnesses. Others’ testimony was problematic or inconsistent.

And the Hoovers who had ratted out their jail guards certainly had reason to lie. After all, they were offering information in hopes of receiving lighter sentences.

Watson completed her investigation last April and forwarded her report to the Multnomah County District Attorney’s Office, which assigned it to senior deputy district attorney JR Ujifusa.

Despite working closely with the sheriff’s office, county prosecutors declined to hand off the case to prosecutors at another agency. “The prudent thing to do would have been to avoid any potential conflict, and even the appearance of conflict, by having another agency take care of it,” says Sandy Chung, executive director of the ACLU of Oregon. An agency spokesperson said it wasn’t necessary because “the work of deputies in the Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office’s jail division is insulated from the work of attorneys in our office.”

Still, Ujifusa was no stranger to complicated cases. He’d developed a specialty prosecuting human trafficking cases during his nearly two decades at the DA’s office.

He was handed the Oregon State Police’s investigation and, for months, spent time every day reviewing documents. “These are very serious allegations,” he told WW.

However, Ujifusa admitted, he lacked much in the way of physical proof. No camera footage showed the assaults. There was no electronic record of when cell doors were opened and by whom. The injuries to inmates could be written off as attempts at self-harm. (A homeless man, for instance, identified two Hoovers who assaulted him, leaving a bloody gash on his face, but later changed his story to say he’d fallen from his bed.)

As for the incriminating jailhouse phone calls in which Hoovers described their collusion with deputies and their beatings of rivals? Too “insufficiently detailed,” Ujifusa wrote in a November memo.

Ultimately, the deputy DA decided he didn’t have enough evidence to prove the case against the three deputies “beyond a reasonable doubt” and declined to press charges. Without hard evidence, such as video footage or electronic door records, he tells WW, “we didn’t feel we had enough.”

Still, his two-page memo raised questions about a lack of oversight at the jail. “There were a lot of concerning things going on in that dorm,” he tells WW. For example: Why were Valdovinos and Sacirovic so apparently eager to work a dorm that other deputies avoided?

He recommended the investigation be handed over to internal affairs, which requires a lower threshold of proof to impose disciplinary action. On Feb. 20, Sheriff Nicole Morrisey O’Donnell announced she was appointing an “independent investigator.”

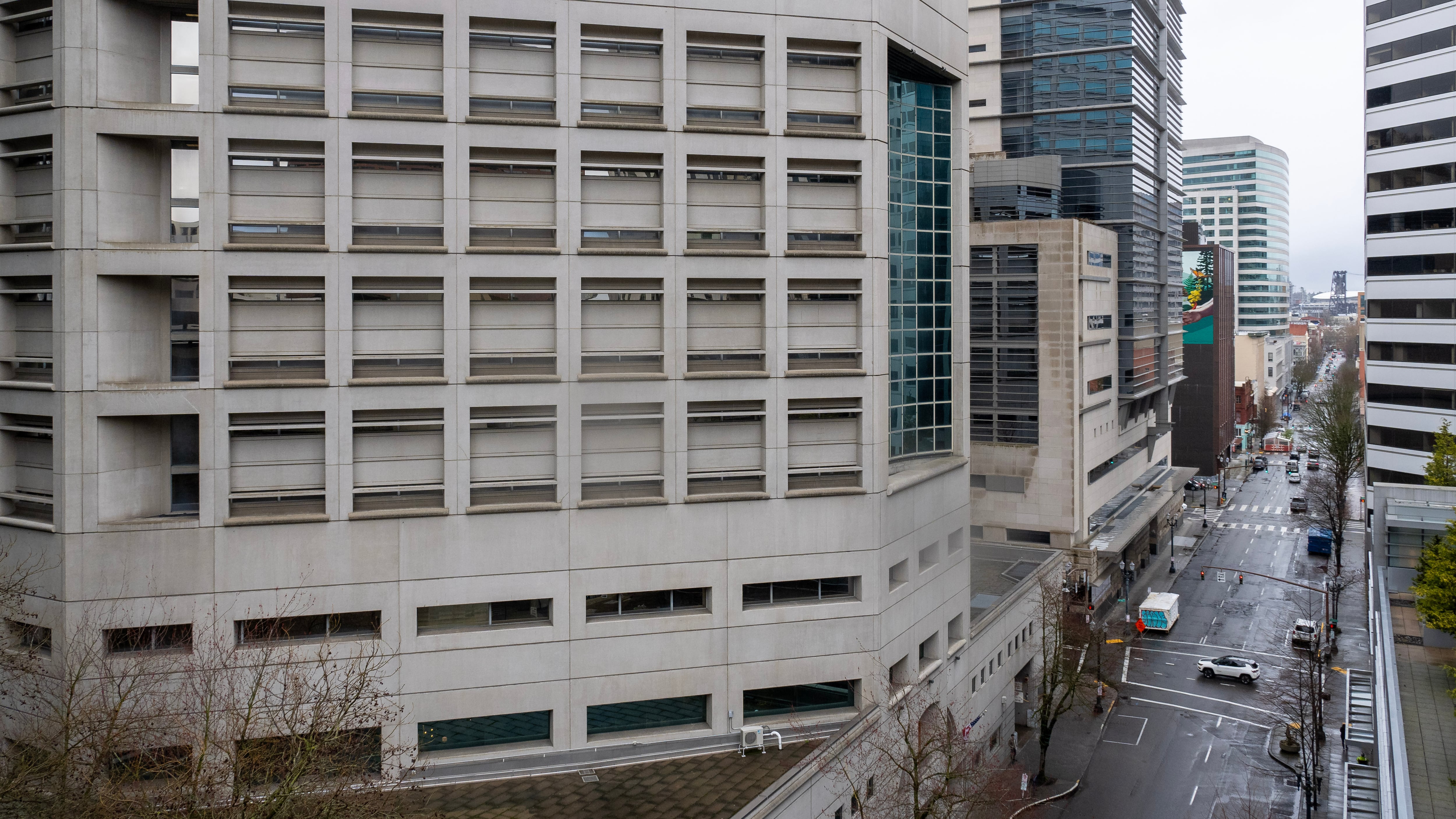

The investigatory process has now taken over a year, during which conditions inside the jails have only deteriorated, but for different reasons. The jails are short-staffed and struggling to provide basic health care. Since the beginning of 2023, seven inmates have died from causes that have included suicide and fentanyl overdoses.

Read our cover story: What Happened in Hoover Jail.