At first glance, Dr. Frank Li’s history suggests he’s the last person who should be allowed to open a psilocybin service center, where people go to take the legal psychedelic mushroom trips that became available in Oregon last summer.

Li ran a chain of pain clinics in the state of Washington until 2016, when state regulators suspended his medical license, alleging that use of drugs his clinics prescribed had contributed to the deaths of 18 people who were his patients at the time, or had been in the recent past.

The U.S. Department of Justice came after him, too, alleging that he billed Medicare and Medicaid for thousands of unnecessary urine tests at a lab that he owned. He agreed to pay $2.85 million to settle those charges, on top of a lifetime ban from treating chronic pain.

Despite all that, the Oregon Health Authority granted Li permission last November to operate a psilocybin service center. He opened Immersive Therapies on Northwest Quimby Street in January.

Oregon Psilocybin Services, the branch of OHA that administers the mushroom program passed by voters in 2020, says it received a complaint about Li during the application process and halted it to investigate. “Upon completion of the investigation, OPS determined the facts did not support a denial, the applicant passed the background check, and the applicant met all requirements under Oregon law to be licensed,” the agency said.

That may sound like a misstep by OHA. But to hear Li and his defenders tell it, the mistake was by Washington state regulators, who banished a doctor who was trying to ease thousands of addicts off pain meds slowly and safely so they wouldn’t turn to scourges like fentanyl in search of relief.

Li says his former company, Seattle Pain Center, treated 33,000 people over eight years. Almost all arrived dependent on high-dose opioids, and he got 22,000 of them clean, he claims.

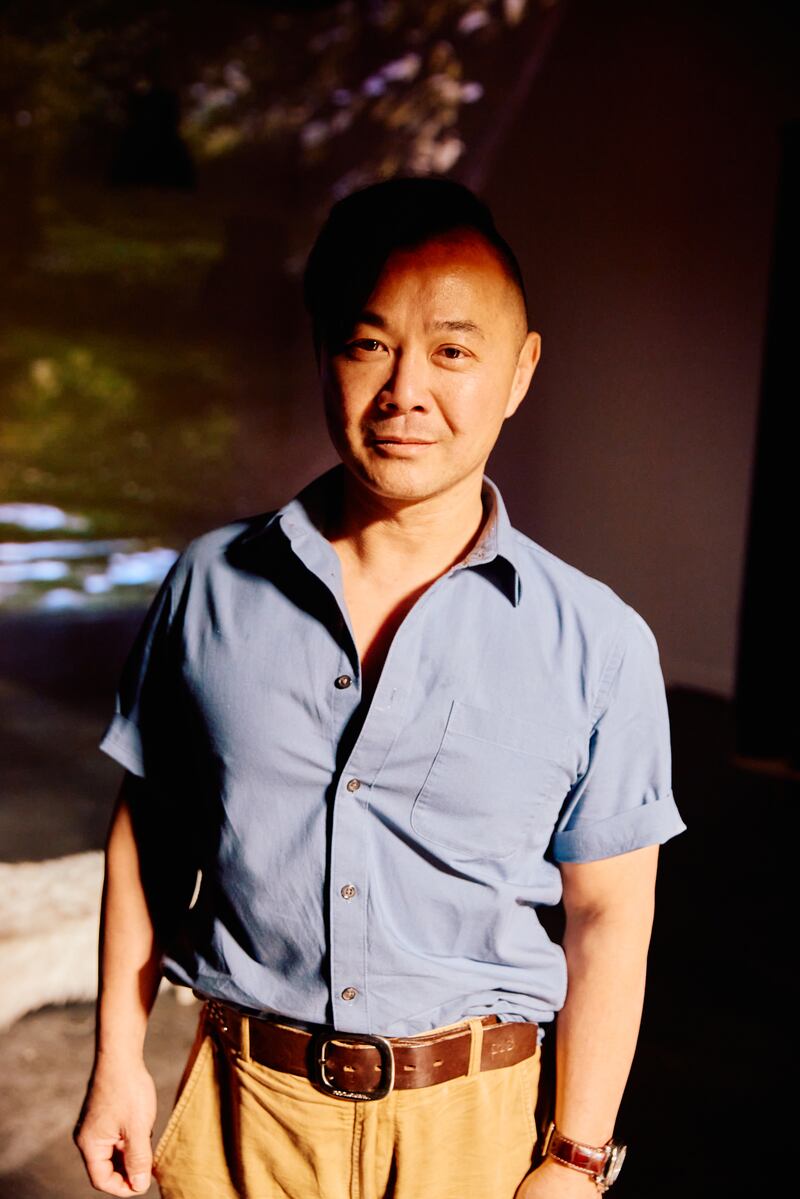

“Our goal was to soft-land them,” Li, 56, told WW during six hours of interviews. “Taking people off drugs too fast exposes a hole that’s not filled. They go to the streets, and that’s not a win.”

The world has started coming around to Li’s way of thinking. In September 2019, the Washington Department of Health sent a letter to doctors clarifying its opioid prescribing rules because it had received reports of patients being taken off too quickly and others who couldn’t find providers willing to take care of them.

“Abruptly tapering or discontinuing opioids in a patient who is physically dependent may cause serious patient harms, including severe withdrawal symptoms, uncontrolled pain, psychological distress and, in rare instances, suicide,” the Washington Health Department said.

In January, Oregon updated its guidance for doctors prescribing opioids, too.

The reversals illustrate the shifting ground below Li’s career reinvention. From one perspective, Oregon’s psilocybin program is the last refuge of a scoundrel, providing him with clients in an environment largely free from regulatory meddling. From another, it provides a haven where Frank Li can use different tools to tackle some of the toughest problems in public health.

Some studies show that psychedelics like psilocybin can curb addiction to alcohol, tobacco and even opioids. It has shown promise as a treatment for depression, too. And researchers at the University of Michigan are studying psilocybin for pain relief, Li’s specialty.

Those prospects, Li says, are his motivation.

Frank “Danger” Li grew up in Atlanta, the son of Taiwanese immigrants. His father was a nuclear engineer whose career was sidelined by the Three Mile Island disaster. Even so, Li followed his father’s lead and studied engineering—electrical and biomedical—at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Attending medical school at the University of North Carolina, he got a new driver’s license, and when asked for his middle name, he jokingly quoted Austin Powers: “Danger is my middle name.” It went on his license, and stuck.

Li did his residency in anesthesiology at the University of California, Irvine, then post-doctoral work in pain management at UCLA. It was the 1990s, and medicine had declared a war on pain. Doctors were reprimanded by hospitals if patients felt any. Many doctors considered opioids a wonder drug back then because they didn’t harm the stomach the way other painkillers do.

Out of school, Li worked in Beverly Hills for seven years, specializing in implanting pain pumps—which send meds straight to the fluid surrounding the spinal cord.

Li moved to Washington and opened the Seattle Pain Center in 2008. Two years later, he says, Washington’s Agency Medical Directors’ Group, a coalition of health regulators, invited him to help develop guidelines for treating pain that’s not related to cancer. Soon after, he opened his practice to Medicaid patients, who are often the most difficult to treat because of adverse life events.

“We were overwhelmed by primary care doctors sending us patients,” Li says.

Li opened one new clinic a year to meet demand. Many Medicaid patients lost access to their medications when clinics swore off prescribing opioids—by now deemed dangerous—leaving Seattle Pain Center to pick up the slack. Soon, it had eight clinics, four other fellowship-trained doctors, and 140 employees. Li says almost all of the center’s Medicaid patients arrived with some sort of drug dependency.

“We were the safety net for the community,” says Phil Rosewater, a health care administrator who became employee No. 25. They very rarely put people on opioids, he says, but, rather, did everything to get them off. “We would titrate people down. Every visit was a trench war.”

State and federal regulators saw it differently.

Records from the Washington Medical Quality Assurance Commission show that a 35-year-old woman, called “Patient B,” died from “acute methadone intoxication” on Jan. 25, 2010, three days after Seattle Pain Center prescribed her methadone and Norco (a combination of hydrocodone and acetaminophen). She had a history of “cocaine overdose” and mental health issues.

Five more patients died in 2011, followed by two in 2012, four in 2013, and one each in 2014 and 2015, according to state records. The dates of four other deaths aren’t specified.

One of the patients had been discharged by Li months before. In many cases, drugs appeared to be a contributor, at most. One patient had a heart attack. Another had a history of hospitalization for respiratory failure. Yet another had abscesses in his lungs and emphysema.

One patient, a 58-year-old man, died when his vehicle veered across a highway median and collided with a logging truck. He had a can of malt liquor wedged between his leg and the gearshift. A toxicology report revealed oxycodone in his blood. He had filled a prescription at Seattle Pain Center 19 days before the crash.

“If people had opioids on board, coroners would put that as a cause of death,” Li says.

The hammer came down on July 14, 2016, when the Washington Medical Commission suspended his medical license.

Li wasn’t charged with a crime, and his clinics were allowed to stay open, but insurers stopped paying claims at his clinics. He stayed open for two months, spending $750,000 out of his retirement savings on staff salaries and rent, he says, as he tried to find other clinics to take 8,000 patients. “A lot of patients suffered when his clinic shut down,” says a former patient, speaking on condition of anonymity.

In September 2017, the city of Seattle sued him alongside opioid manufacturer Purdue Pharma, calling Seattle Pain Center the “primary illicit source” of opioids in the city. “SPC, in short, was a pill mill,” attorneys for Seattle said in a court filing.

“SPC practitioners were encouraged to work fast and cut corners,” the city’s filing continued. “Patients typically would be seen for less than five minutes, or just about the time it took to write an opioid prescription.”

The case is ongoing, Li says.

Li fought the state’s charges initially, hiring a lawyer and filing an 18-page rebuttal in October 2016 in which he took each case of the 18 deceased patients in turn. Eventually, he gave up. His parents were distraught. He drank heavily. His engagement to be married was collapsing under the strain.

“I didn’t have the psychological fortitude that I thought I had,” Li says.

After two years of fighting, he signed a stipulation of facts in March 2018, agreeing to a laundry list of sanctions, including a three-year suspension of his medical license (with credit for two years already served) and 10 years of probation. Once reinstated as a doctor, he would never be allowed to prescribe more than seven days of opioids at one time. Li is still awaiting word from Washington on whether his license will be restored because the ethics courses they required him to take were delayed by the pandemic.

Li considered returning to California to practice general medicine. A number of physicians wrote letters of support, saying Li was “unfairly targeted” by Washington “for political reasons, in order to satisfy the public that officials were taking action to curb opioid abuse, and not because his care was truly substandard.” But California revoked his license in October 2018.

In May 2020, Li agreed to pay $2.85 million to settle federal charges that he had billed Medicaid and other federal insurers for unnecessary urine tests at Northwest Analytics, the lab he owned. He’s still making payments, Li says.

Li was near his nadir, he says, when he heard promising things about ketamine, a powerful anesthetic that’s used to treat depression. He read up on it and gave it a try in 2020 under the supervision of Dr. Phil Wolfson, a California-based ketamine pioneer.

It was a big leap. “As a pain doctor, you don’t ever take any substances,” Li says.

Ketamine was a revelation. “I melded into a greater consciousness where there was simultaneous joy and suffering,” Li says. “Having a glimpse of how it all balanced out gave me some peace.”

As it does for many people, ketamine led Li to psilocybin. He tried it at a resort in Jamaica, where it’s legal. The program was a little haphazard, he says, but he had a positive experience. He pored over the shroom literature and saw great promise.

“I like the way that psilocybin approaches a problem,” Li says. “It’s not masking things. A lot of health care deals with symptoms rather than the root causes.”

Keen to work with mushrooms, Li moved to Oregon and, in March 2023, leased some industrial space on Northwest Quimby Street.

He partnered with Tony Peniche, an entrepreneur (whiskey, exotic bacon) who walked his own hellish path to psilocybin. On Jan. 1, 2020, just before the pandemic, Peniche’s wife left him. Soon, he tells WW, he was drinking a half gallon of Fireball whiskey every day or so. Fed up, Peniche rented an Airbnb in Santa Cruz, Calif., for a month in the summer of 2022, left the booze behind, worked, worked out—and microdosed psilocybin every day.

“When the anxiety of ‘I need to drink, I need to drink’ came up, I would just microdose mushrooms,” Peniche says. “And that feeling just went away.”

No one lends money to service centers because psilocybin is illegal under federal law, so Li and Peniche are footing the bill themselves.

“This is my life savings,” Li says, sipping tea in a pair of black Carhartt overalls.

Although it’s possible he’s a terrific con man, Li doesn’t appear a pill-mill refugee looking to make a fast buck with another controlled substance. He’s done most of the work on his service center by himself, painting door frames, building furniture, and curating the psilocybin-chic décor (polished concrete, vibrant shag carpet, a psychedelic deer sculpture).

Nor are legal shrooms likely to make him rich. The startup costs run in the thousands of dollars. Trained facilitators, the people who sit with trippers, often operate out of their homes or in Airbnbs, depriving service centers of revenue. Right now, only one or two sessions a day happen at Immersive, led by a contracted facilitator. (Li himself doesn’t have that license, so he must pay someone who does.)

Li hopes to get to four sessions a day, and to host group sessions. He charges between $299 and $399 to use a room in his center (depending on size). Psilocybin is $5 per milligram. His facilitators charge between $600 and $1,500 for prep sessions, a trip session, and integration meetings afterward. Group sessions start at $699, including room and facilitator fees.

Like many people, Li could have turned to black-market trip-sitting (“The Mushroom Underground,” WW, April 26, 2023). It’s cheaper, and customers are willing to do it. But as a medical professional, Li says he respects regulation and regulators, even if they shut him down once.

“All this work was done below ground, but now that it’s coming above ground, we’re going to be more aware of complications,” Li says. “We are going to report adverse events. That’s one of the rules. Nothing is gained by putting our heads in the sand.”

Some have taken notice of his troubled history. Recently, according to a redacted record, someone complained to OHA about his “past professional history, including medical board disciplinary action and federal legal action,” according to the agency.

The complaint made news in the shroom world. A writer named Jules Evans publicized the complaint on his Substack. Despite the bad publicity, Li says he’s committed to operating in the sunshine.

“With what I went through, I can add value in making sure that we follow all regulations and that we get beyond this honeymoon period where we think, ‘My God, psilocybin can help anything and everything. You just take it, and all your problems go away,’” Li says.

Li has seen where that kind of magical thinking ends.