If you’re looking for a nursing home in Oregon, a good place to start might be the website of the state agency that regulates them, the Department of Human Services. It has a nifty map of long-term care facilities and, crucially, a red box denoting whether each one is facing formal regulatory sanctions—a sign, perhaps, to look elsewhere.

But, in some cases involving serious sanctions, that red box isn’t there. That’s because the agency quietly signed a “letter of agreement” outlining its demands of the facility. These letters can be used in lieu of a “condition” being placed on its license, the regulatory black mark that triggers the red box.

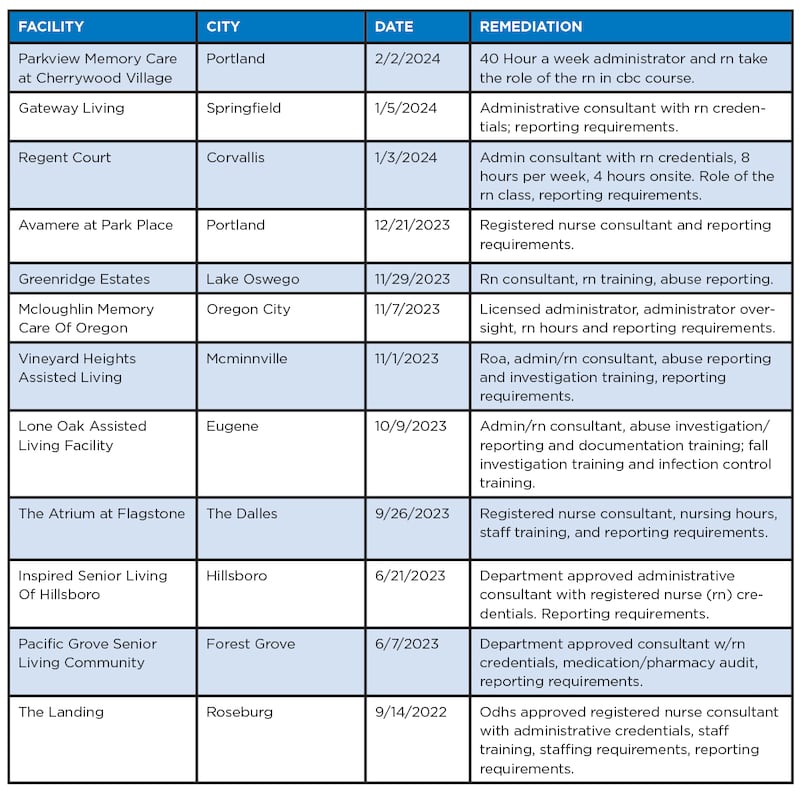

The result is that the public has been largely left unaware of when and where the agency chooses to use these agreements, of which there are currently around a dozen. The requirements outlined in the agreements reviewed by WW range from halting new admissions to hiring a professional consultant to review operations.

“It’s unacceptable,” says the state’s long-term care ombudsman, Fred Steele. “There’s concerns by the regulatory agency, and the public isn’t aware.”

Steele has been a thorn in DHS’s side lately. Earlier this month, his office issued a blistering report demanding an independent audit of the agency following what it says was the preventable death of an 83-year-old resident of a Sandy memory care facility, Mt. Hood Senior Living.

But his concerns about the regulatory agency’s transparency, or lack thereof, go back much further. In 2022, he brought up the agency’s use of letters of agreement at a legislative committee hearing, saying lawmakers should take a look at the fact they’re “kept secret from the public.”

The agency’s director in charge of the program responded with a memo noting that the agreements were generally used when a facility “has provided assurance of safety, a willingness to work expeditiously to resolve any and all identified issues.”

That’s still the agency’s position. “Letters of agreement are a tool in incentivizing licensed facilities to address problems proactively,” DHS spokeswoman Elisa Williams told WW in a statement this week. “ODHS may accept a letter of agreement, but it does not prevent ODHS from taking regulatory action to address the compliance issue if that is ultimately determined to be warranted.”

That’s cold comfort to Steele, who argues that letters of agreement are fundamentally the same as “conditions” and are simply a way for senior care homes to avoid a stain on their record after inspectors uncover serious problems.

The letters don’t explain exactly what inspectors found, but do include dates of the failed inspections. WW reviewed the inspection reports and found serious infractions, including a resident being denied medication for a month at Gateway Living in Springfield in October as the facility “was awaiting delivery of supplies.” (A spokesperson declined to comment on inspectors’ findings or the subsequent agreement with the state.) Some of the agreements have remained in effect for years.

“The use of these letters of agreement is a representation of a regulatory system—intended to be consumer protection oriented—that tends to be supportive of private business first,” Steele tells WW. He pointed to Mt. Hood Senior Living as an example of the consequences.

Even the Oregon Health Care Association, the long-term care facilities’ trade association, is on board with more transparency, to a point.

“OHCA supports having the state include a designation that a letter of agreement is currently in place for a provider on its website,” spokeswoman Rosie Ward said in a statement. But, she later clarified, the association’s support hinges on the designation not explaining the content of the agreement.

Still, it’s a public record—if you know to ask. Here’s a list of agreements currently in effect, as of February. (DHS didn’t provide WW with a current list as of press deadline, so we’re using one provided to the ombudsman in February.)