Last summer, a new drug and mental health treatment center set up shop in Northeast Portland. The for-profit company, named Wevolve, offered what’s known as intensive outpatient treatment, which can involve up to 20 hours a week of therapy and other services.

It couldn’t have come at a better time. State officials say Oregon, which has one of the highest rates of substance use disorder and mental illness in the country, has only half the treatment programs it needs.

But last week, the clinic was nearly run out of town by Multnomah County officials.

The dispute began sometime earlier this month when another treatment center, the Native American Rehabilitation Association of the Northwest, learned that one of its clients had been recruited away from NARA by “African missionaries who he met outside the Rescue Mission,” according to a description of his claims later distributed by Multnomah County officials.

The story passed from the client through NARA to the county: After Wevolve staff offered him free housing and clothing, he was sent to a Gresham house, supposedly controlled by Wevolve, with “six people sharing the living room to sleep,” the county said.

After NARA began asking questions, and reported the situation to police, the house was emptied, according to the county alert. But Gresham police weren’t convinced any crime had occurred. Neither, in fact, was the county, which would later determine NARA’s claims didn’t amount to abuse.

Still, on May 20, the Multnomah County Health Department’s top compliance officer drafted a “fraud alert” that was subsequently sent to a pair of local email listservs warning that the county had received word that Wevolve “may be preying on people in our community.” The email was sent to more than 500 addresses.

After WW asked about it the next day, the county backpedaled within hours and retracted its claims.

The reason: The county hadn’t bothered to confirm any of the allegations.

County officials now say it was an innocent mistake. Wevolve contends it’s the victim of a racist harassment campaign by NARA, a rival for the same clients. Wevolve is Muslim-run, and its spokesperson says it’s been singled out for scrutiny due to its employees’ accents.

It’s still unclear whether Wevolve was unfairly targeted by overeager officials attempting to protect vulnerable patients, or if this was the latest example of opportunists capitalizing on Portland’s desperate need for places where people can get clean and sober. The Oregon Health Authority has opened an investigation into Wevolve but won’t discuss what it’s probing.

Still, the saga demonstrates how a flood of public dollars has attracted new players, testing the limits of often uncoordinated and unwieldy government regulatory agencies. Oregon delegates many of its behavioral health programs to its counties, but the incident shows blind spots in their coordination. Multnomah County officials didn’t appear initially aware, for example, that Wevolve was in fact in good standing with its state licensor.

Addiction treatment clinics are licensed by the state. But Oregon doesn’t mandate certification for recovery homes. As a result, it’s hard to know who controls the alleged Gresham flop house—Wevolve denies it does.

Tony Vezina, who runs a Portland youth recovery nonprofit, says he hadn’t heard of Wevolve and doesn’t know if the county’s allegations had merit. He hasn’t heard of organized rehab fraud reaching Oregon— yet.

But, he says, the deluge of money being given out to house Portlanders in recovery creates opportunities for bad actors. “There’s so much money because there’s a crisis,” he says. “There’s real opportunity for people to take advantage.”

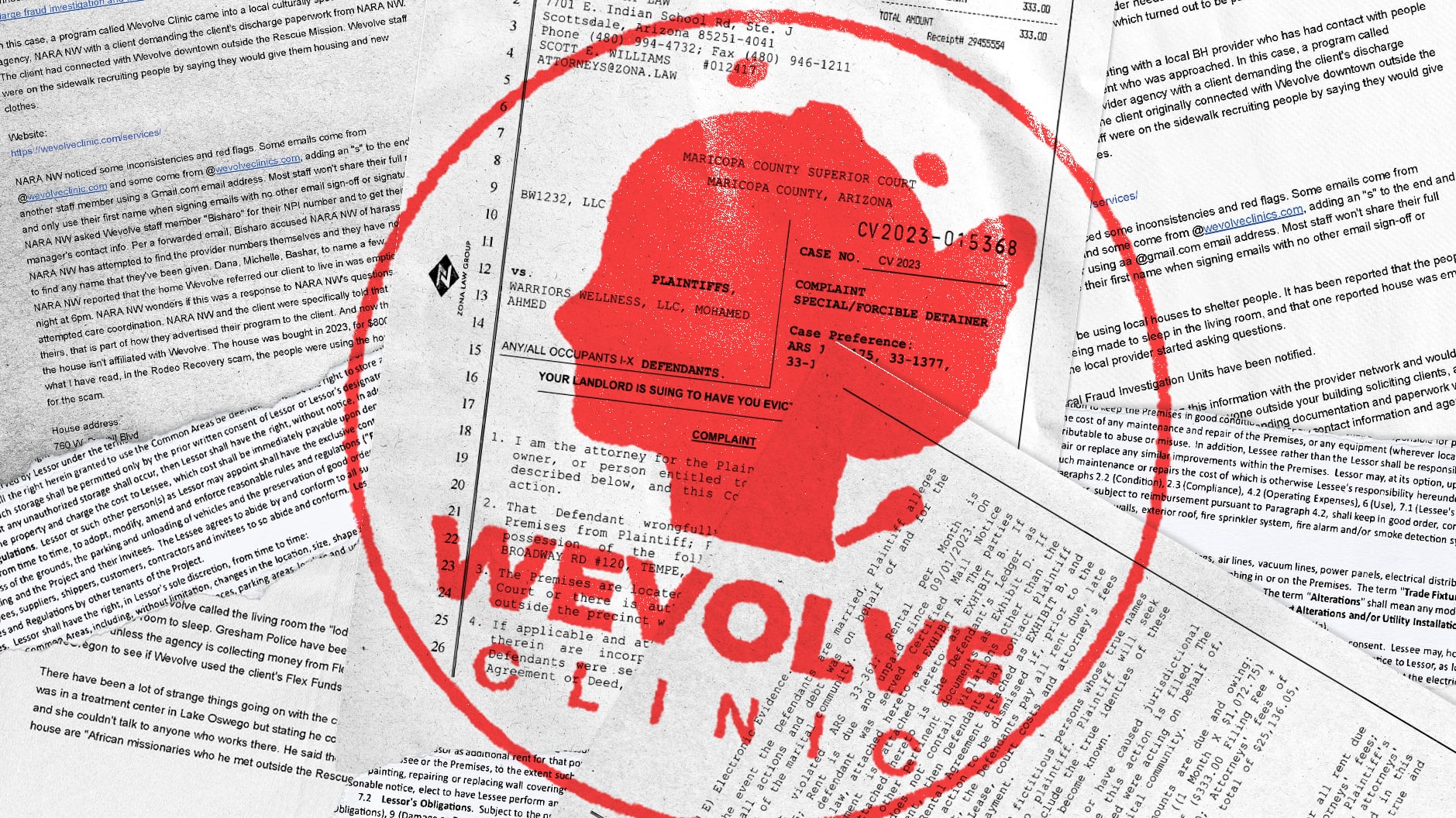

The apparent owner of Wevolve is Muhamad Ahmed, who registered the business with the state last August and whose personal cellphone is used by clinic staff. Someone with the same name tried to start up a similar operation, using the same phone number, in Arizona last year—and, court records show, was evicted after failing to pay rent.

When WW showed up at the Portland clinic’s location, the third floor of a Kerns office building, no one answered the door. The clinic administrator who returned WW’s call said her name was “Lucky” and refused to answer any questions about the clinic’s past. Ahmed, she said, declined to comment.

Still, the organization insists it’s aboveboard. “Everything that has been said about us has been a lie,” Lucky says.

The clinic’s administrator, named in business registration filings and county emails obtained by WW, is Fartun Ali. In these emails, Ali claims her clinic was targeted because her employees speak with an accent. “This is an obvious example of racism and bigotry,” she wrote May 22.

NARA and its CEO, Jackie Mercer, have not responded to WW’s requests for comment.

The county has been on high alert for rehab scams since last summer. In August, local shelters complained to the Joint Office of Homeless Services about an apparent scam involving a California company called “Rodeo Recovery.”

Outreach workers purportedly representing the rehab visited Portland shelters and food pantries, handed out glossy flyers with pictures of palm trees, and promised free airfare to Rodeo’s Beverly Hills facility.

But the website provided by the workers appeared, to a shelter employee, to be fake. And when the employee called the phone number, “the person was unable to provide further information and hung up.”

Jen Gulzow, the county health department’s chief compliance officer, was concerned about the “potential scam” and reported it to law enforcement. (DOJ confirmed it’s not investigating Rodeo, but declined to say anything about Wevolve.)

Her concerns, at least according to government officials, appeared to have some merit. The facility was not what it seemed. The city of Beverly Hills sued Rodeo in 2020, accusing it of luring in out-of-state patients with “the promise of a high-end, ‘easy living’ experience” and then, when they arrived, cramming them into garages and other “dilapidated structures.”

Last November, the insurer Aetna sued Rodeo too, claiming its owners were involved in a racketeering scheme to exploit patients and defraud insurers. Scams of this sort have been uncovered across the country, from California to Florida to Arizona, where the state’s Medicaid program announced last year it was suspending nearly 400 “fraudulent” treatment providers targeting Native Americans.

The upshot is that such scams were on Gulzow’s mind when she received the Wevolve complaint on May 17. “It sounds similar to the situation I connected with you regarding Rodeo Recovery,” she told providers in the fraud alert sent out three days later with a link to media coverage of Aetna’s lawsuit against Rodeo.

She came, quickly, to regret it. The next day, two hours after WW asked about it, Gulzow sent out an apology and acknowledged the county hadn’t yet investigated, let alone confirmed, the allegations against Wevolve. “Staff were operating solely out of concern for the safety of the people being served,” a spokesperson tells WW.

Gulzow herself would later say the document was a draft, sent out accidentally “prior to the report being fully investigated.”

In fact, the county would never do so. According to county spokeswoman Sarah Dean, NARA’s claims didn’t even rise to the level of being worthy of investigation for “abuse,” so no investigation was ever opened.

But the county isn’t the only government agency overseeing behavioral health treatment clinics. So does the Oregon Health Authority, which certifies them. According to Gulzow, OHA didn’t share the county’s concerns. On May 21, in her email retracting her prior allegations against Wevolve and encouraging county contractors to work with the company, she wrote, “OHA has NO concerns with Wevolve.”

But two days later, an OHA spokesman confirmed to WW that it was, in fact, investigating Wevolve. The spokesman, Timothy Heider, would not say when the investigation was opened or why.

As insurance fraud has proliferated, other states have found different ways to crack down on fraudulent sober living homes. Florida created a task force to regulate them. Arizona and a few other states have required they be licensed.

Vezina, the drug policy commission chair, says Oregon should do that, too. He’s pushing lawmakers to introduce a bill mandating licensing next year.

That would let clients—and county officials—look up online whether a facility is reputable. “We saw the money coming in, and we wanted to protect the model,” he says. “It’s kind of a no-brainer.”