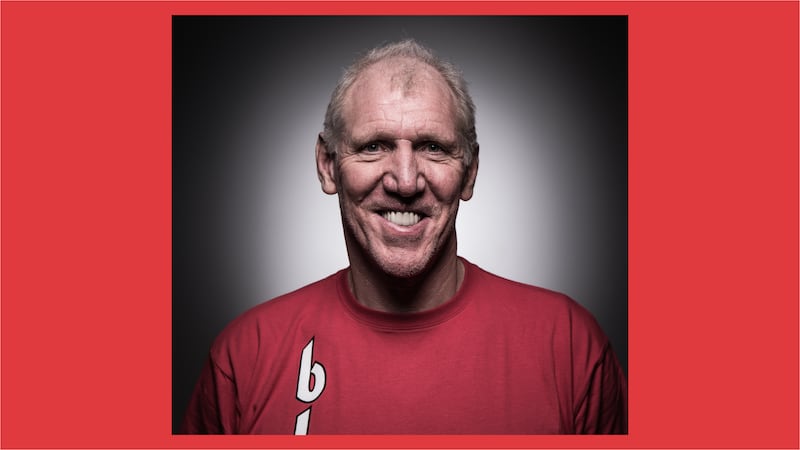

Bill Walton’s death last week, at 71 from cancer, seemed somehow unreal. His place in Portland felt both distant (he hadn’t lived here since 1978) and comfortingly permanent, a fact of geography, like Mount Hood reappearing every morning at sunrise. (That is, if the mountain appeared during cable broadcasts of Ducks games spewing superlatives.) Thanks to his role as the nucleus of the Trail Blazers’ only NBA championship team, Walton had what writers like to describe as immortality. Except it wasn’t true. For the past week, Blazermaniacs looked for some way to restore Walton—perhaps a statue outside Moda Center, as U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) suggested—but it didn’t change the fact that a colossus who once grinned his way across Oregon had vanished.

Larry Colton can’t bring Walton back. But he got closer to the big redhead than most. At least for a few minutes, until Walton started pedaling.

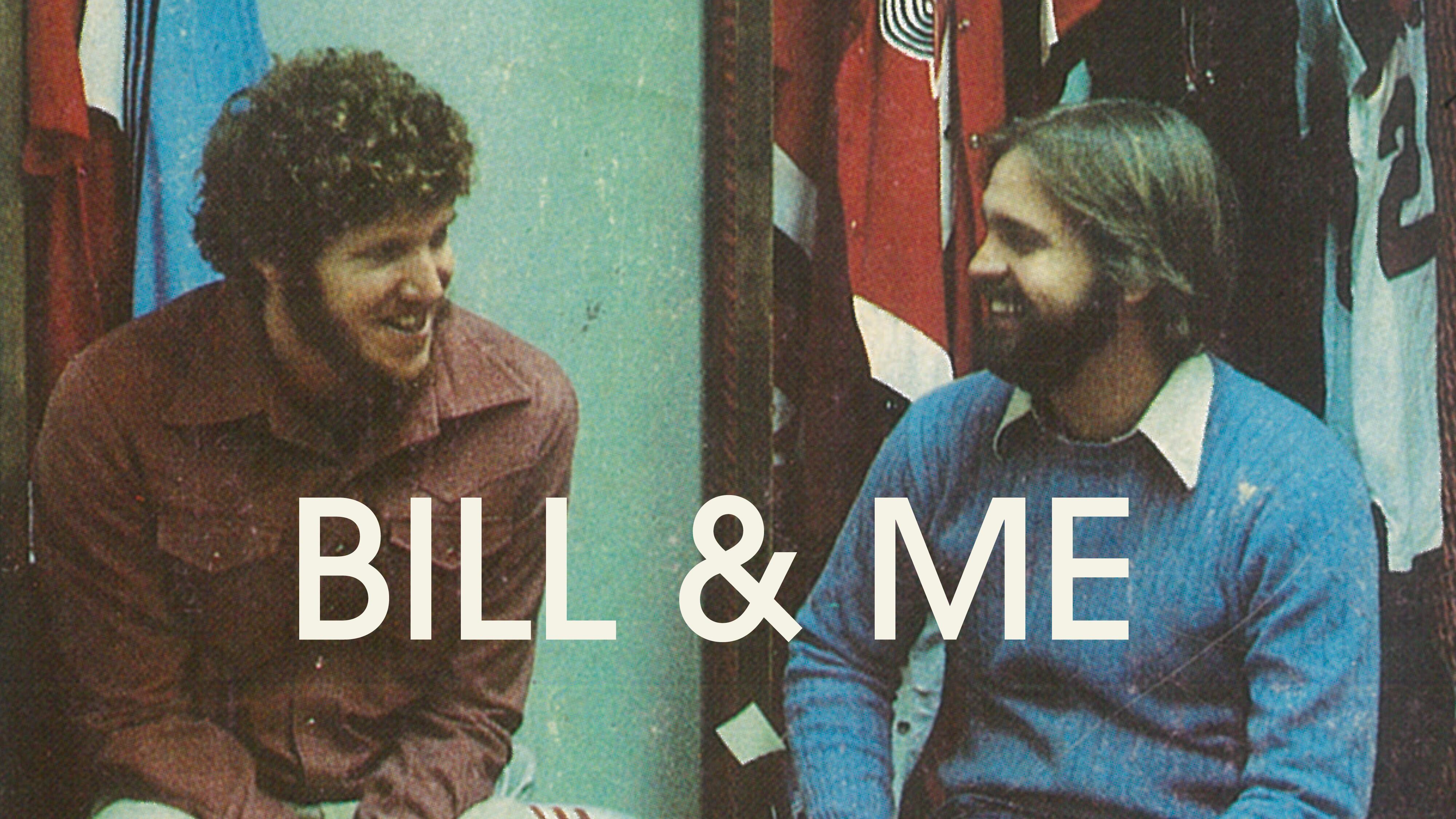

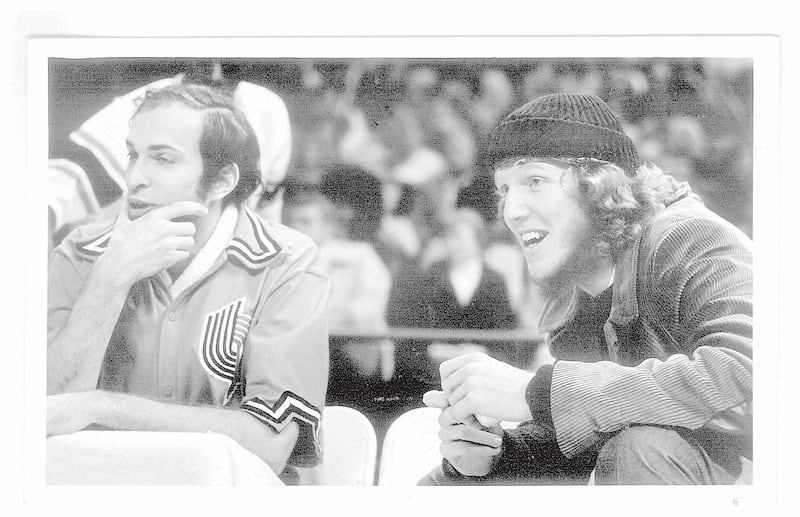

In the summer of 1977, weeks after the Blazers’ championship parade, filmmaker Don Zavin invited Colton to join Walton on a bike ride down Highway 101 on the Oregon Coast. Zavin was making an odd, lyrical documentary about the Blazers and their counterculture superstar, but the director worried that Walton, who battled a stutter, wouldn’t talk without a conversational partner. So Colton pulled his Schwinn three-speed out of the garage and tried to keep up.

Colton is himself a mythic figure of Oregon letters. A former college baseball phenom (who still holds the Cal Berkeley single-game strikeout record at 19), Colton pitched two innings for the Philadelphia Phillies, before a shoulder separation ended his career. He became a high school English teacher and then freelance writer, covering sports for Portland newspapers. Colton wrote a column for WW called Pillars of Portland. It was civic sociology as soap opera; the recurring characters had names like Wes Hills and Laurel Hurst. It was the talk of the town for much of the 1980s. Colton would go on to author five books, and in 2005 he founded a literary festival called Wordstock. You know it now as the Portland Book Festival.

When news arrived of Walton’s death two weeks ago, our first call was to Colton, 81, whose first book, Idol Time, examined the aftermath of the Blazers’ championship season. Within hours, he agreed to take a couple days off of work on his latest book, Larry’s Last Stand, to pen a few memories of his interactions with Walton. He sent us nearly 5,000 words, not just about the bike trip, but about smoking joints with a coach, a death threat in Los Angeles, and the role Walton’s onetime roommate in Northwest Portland played in the flight from justice of Patty Hearst.

Whether you were there for the glory days when Rip City was Red Hot and Rollin’, or are new to the legend of Bill Walton, we hope you’ll find it an interesting read. This is the story of the guy who stood next to the luckiest guy in the world.

—Aaron Mesh, WW Managing Editor

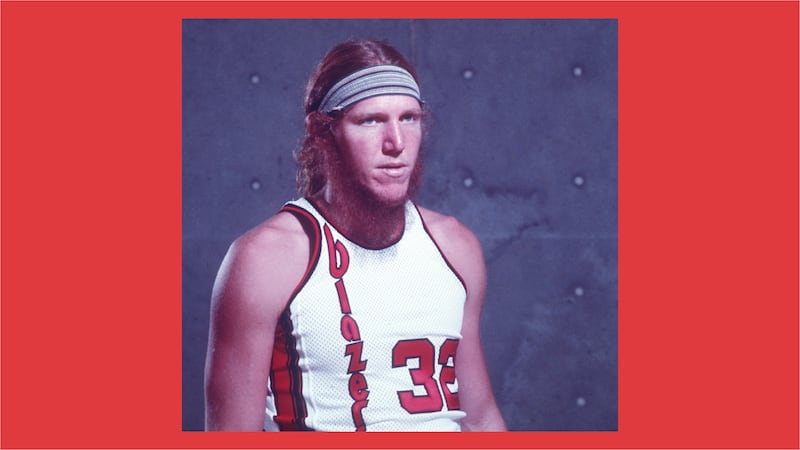

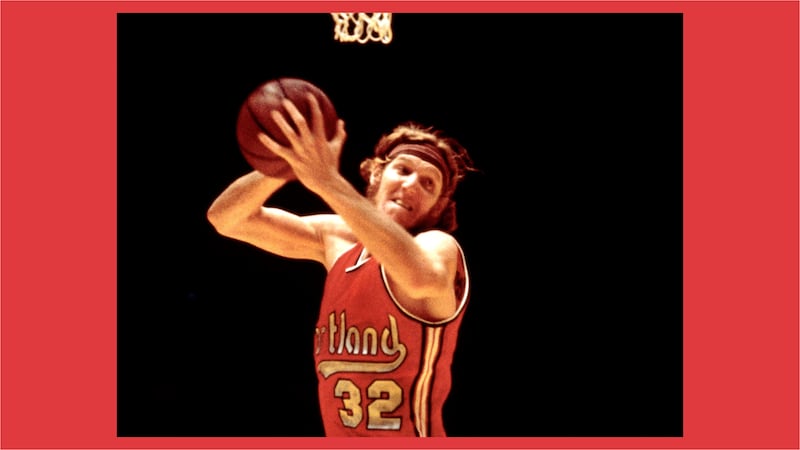

Not many athletes were more suited to a city they played in than Bill Walton in Portland. He was alternative, liberal, white, and eager for love.

Basketball was his platform, but he was so much more. Anybody who lived in Portland during his too-brief reign as the King of Basketball has a fond memory of him, either leading the team to the world championship or enjoying his place as a cherished but eccentric member of the community, showing up at Wallace Park for a pickup game decked out in a Grateful Dead T-shirt.

He brought unbridled joy and nonconformity to the banks of the Willamette, something our city could use more of these days. He was not without his flaws, but that’s part of why we loved him so much.

Here are my 10 fondest Walton memories.

The First Time I Met the Big Redhead

It was the summer of 1974. Bill had just moved to Portland after being the first pick in the NBA draft, and lived in a rented house in Sellwood. I was a teacher at John Adams High, an alternative school in Northeast Portland. His signing bonus was $200,000—peanuts compared to today—while I’d just gotten a raise to an annual salary of $8,400.

The new assistant coach for the Blazers was Tom Meschery, a 10-year NBA veteran and as close to a renaissance man as the league has ever produced. Born in Manchuria, raised in San Francisco, and nicknamed “the Mad Russian,” he was fluent in three languages and had just graduated from the University of Iowa Writers Workshop, the preeminent graduate writing program in America. He’d published two books of poetry, but when new Blazers’ head coach Lenny Wilkens offered him the chance to coach the Blazers’ big men, including Walton, Meschery jumped all over it. Who wouldn’t want to coach the most dominant center the college game had ever seen?

When Tom first arrived in Portland, we were already friends and he temporarily lived with me and my wife. Although Walton’s first Blazer practice was still a month away, the outpouring of anticipation made Multnomah Falls’ cascade look like a trickle.

“Walton just invited me to come and visit him at his house,” announced Meschery. “It’ll be a chance to get to know a little more about him. Want to come with me?”

Of course I did. I’d followed Bill’s career at UCLA, and not only did I think he was an unbelievable talent, but I admired his anti-war persona. He’d been arrested at a protest in Westwood. This guy’s commitment went way deeper than the peace sticker on the back of my VW van.

It was in the middle of the afternoon when we arrived at his house. Bill’s girlfriend Susan Guth offered us tea and water. Two other people—Jack and Mickey Scott—had already taken up residency with them. Jack Scott was an established leader in the sports counterculture movement, such as it was. It took about two minutes for me to peg Scott a pompous, opportunistic bore. But he meant well and, hey, I was just a public schoolteacher tagging along with my friend, the coach.

About five minutes into the meet-and-greet, Walton excused himself and retreated to a bedroom. A couple minutes later, he reappeared, smoking a joint. He offered a hit to Meschery.

An old-school, beer-and-shot-of-whiskey kind of guy, Meschery wanted to be a good guest, especially with a host who had the potential to be the best player on the planet, so he took a Bill Clinton-like hit, immediately started coughing, and passed the joint to me, an experienced toker.

Before becoming a teacher, I had played six years of professional baseball. Even the concept of meeting for coffee with a coach was unthinkable. But sharing a joint? My brain waves were crashing on the shores of incredulity. People went to jail for this. Pot was still 40 years from being legal in Oregon.

Party Like It’s 1975

Later that year, and for reasons I can’t remember, Walton showed up at a New Year’s Eve party my wife and I hosted. His girlfriend Susan also came, as did Walton’s Blazer teammate and former UCLA star Sidney Wicks. Walton had to duck to come through the door, and all the other guests just gawked, as if Jesus had just made a surprise appearance.

Bill and his little entourage didn’t stop to chit-chat with any of the revelers, beelining it straight to a back bedroom, making no effort to mingle. They fired up doobies behind the door. The other guests whispered.

Bill stayed about an hour, leaving before the clock struck midnight, not letting any of the other guests misdirect him to the mistletoe. The easy consensus was that he was aloof, although it was probably more a case of him being uncomfortable and awkward around strangers, a famous 6-foot-11 redhead with a stutter who couldn’t just blend in and didn’t yet have the necessary social skills.

Patty Hearst

It’s well documented that Walton’s first two years with the Blazers were disastrous—too many injuries, too many controversies, too many bad choices. It was during that time that his housemate Jack Scott transported the fugitive Patty Hearst across the country. She had been kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army, a radical terrorist organization that had a national following of, what, three people? Four, if you included Scott, now the headmaster at the School of Opportunism.

I’ll never know why Walton thought it was a good idea to be so closely associated with somebody who “allegedly” drove the most famous fugitive in the world across the country. Scott was at the far-left fringe of the sports world, telling everyone who would listen that the NBA was all about greed. Well, no shit, Sherlock. But if he truly wanted his ace disciple to throw off the yoke of capitalism, he should have had Bill turn in his Mercedes and ride his bike to the Coliseum. Yes, Mr. 23-Year-Old Whole Earth Walton drove a Benz.

A Veiled Death Threat at the Fabulous Forum

Not too long after first meeting Walton, I quit teaching to pursue the lucrative profession of a freelance journalist, writing for The Oregonian and Willamette Week. Or as my now ex-wife put it: “the most irresponsible parenting move ever.” During the Blazers’ run toward the championship, The Oregonian assigned me a feature on the team and sent me to L.A. to cover the Blazers’ Western Conference playoff against the Lakers and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Before the first game, a friend of mine from college introduced me to Sam Gilbert, a wealthy L.A. businessperson and infamous supporter of UCLA basketball. It was well known that he slipped money under the table to the Bruins’ stars, including Walton. (Gilbert died in 1987, but not before UCLA was ordered to disassociate itself from him.)

Sitting in a private suite at the Forum, I told Gilbert I was writing a story about Walton and the Blazers.

“Let me tell you something about that guy,” he fumed. “He’s an ungrateful sunuvabitch.”

Huh? I thought it was supposed to be a lovefest between Gilbert and Walton and all the other UCLA stars.

The problem, according to Gilbert, was that Walton had switched his allegiance to Jack Scott, and according to Gilbert, Scott was an anti-American leech who was brainwashing Walton, turning him against Gilbert and all that was good with America.

“Walton needs to be careful,” declared Gilbert.

“What’ya mean by that?” I asked, as the horn sounded to start Game 1.

“It means whatever you want it to mean,” said Gilbert. “But if he thinks he can mess with me, then he doesn’t know anything about the Jewish Lithuanian mafia.” He formed a gun with his thumb and forefinger, then fired off an imaginary shot.

I had a witness who heard this conversation, a close college friend. So, knowing I had a major scoop—UCLA’s sugar daddy threatening to off its brightest star—I included it in the story I submitted. To verify it, The Oregonian called Gilbert.

“I remember that guy,” he said of me. “He was whacked out on drugs.”

Then they called my friend, the witness. To my dismay, he denied Gilbert ever said anything of the sort. Feeling betrayed, I called to ask him why he lied about it. “You don’t understand, Larry. Nobody messes with Sam Gilbert. And that includes you and your buddy Walton.”

Bike Ride Down the Oregon Coast

A month after the Blazers won the championship in 1977, I got a phone call from Don Zavin, a local filmmaker whom Walton had given permission to film a documentary about him titled Fast Break. This was a big deal. At that point in his career, Bill had been notoriously guarded around the media, one way of hiding his stutter.

“You want to go on a bike ride with Walton down the Oregon Coast?” Zavin asked.

“When?”

“Tomorrow.”

Originally, Bill was supposed to go with a buddy from UCLA, but the guy pulled out at the last second. Zavin wanted Bill to have somebody on mic to talk with on the ride, so I got the call.

“Sure,” I replied. Never mind that my bike was a three-speed Schwinn Varsity with a baby seat on the back. The farthest I’d ever ridden it was 2 miles to Wilshire Park so my 3-year-old daughter Sarah could play on the swings. I had no padded shorts, fancy jersey, or biking shoes. I didn’t even have a helmet.

Turns out, Walton didn’t bring a helmet either. He did, however, have a state-of-the-art English Falcon racing bike that was worth more than my beat-to-shit Chevy Nova.

Less than 24 hours after that call, we were pedaling over Neahkahnie Mountain on Highway 101, a cameraman riding alongside in a Porsche convertible, recording our journey.

It didn’t take long to see a pattern develop. Bill would charge ahead, a world-class athlete in championship shape, with me falling behind, way behind, huffing and puffing. Most of the time, he was so far ahead, I couldn’t even see him. Occasionally, the film crew would double back to make sure I had not been blown off the road by an 18-wheeler. Or sometimes, Susan, Bill’s girlfriend (and eventually the mother of his four sons), would peel back to do a welfare check on me. She was driving their Mercedes.

It didn’t take long to notice a few other things. The first was that Bill would get way ahead and then wait for me to catch up, but as soon as I’d pull up, he’d smile and say, almost sadistically, “OK, let’s hit it.” And off he’d pedal, me still gasping for breath. The second thing was how much my shoulders, back and butt ached. I had done zero training for this journey. It got so bad that the film crew went into Lincoln City and bought me a foam cushion to put under my butt. Nice try, but it didn’t help.

Another thing I noticed was that summer tourists would drive by us in their Camaros and Winnebagos, realize that they’d just passed Bill Walton, and then either screech to a halt or turn around to try and get a picture with him. I didn’t get in any of those photos. Once, we passed a bicyclist who was riding from L.A. to Seattle, and when he rode past us and realized it was Walton, he turned around and pedaled 15 miles in the wrong direction just to ride alongside Bill. I was never close enough to hear what they were talking about.

When I finally pedaled into Newport after two days, Bill was waiting in the middle of the street to greet me with his crooked but effusive smile. As I stood astride my bike, he said two things that I’ve carried with me to this day. The first was this: “I can’t believe you made it the whole way on that piece-of-shit bike with no training before we left. You showed me something.” And then he high-fived me, even though high fives were not really a thing yet.

And then he added this: “Did you hear the news? Elvis died today.”

Common Ground

After the bike ride, it felt like my relationship with Bill had moved to a higher level. He’d read the first thing I’d ever published—a first-person account in The Oregonian of playing for the Portland Mavericks baseball team—and said he liked my writing style. That meant more to me than the $400 I got for writing it. I had also played a couple years for his hometown San Diego Padres, and he claimed he saw me pitch. I wanted to believe him.

Bill was never shy in throwing out compliments, but there were times I wondered if it was just hyperbole, like he later tossed around endless verbal salads during his announcing days. During my time covering Blazer practices, coach Jack Ramsay would occasionally let me shoot buckets during warmups…as long as I wasn’t in the way. But sometimes Bill would ease up behind me, and just as I was ready to cast off, he’d reach over and block my shot. That wasn’t as bad, however, as the time at a clinic on the Warm Springs Reservation when a 10-year-old Native kid went in for a layup and Bill blocked his shot halfway to Hood River.

Dumping on Portland

In the season following the championship, the Blazers and Walton were unstoppable, but it all came crashing down when he hurt his foot. He saw specialist after specialist, and the Blazers gave him the medical attention that you’d expect for the most valuable player in the NBA.

While Bill was out of action on the injured list, his buddy Jack Scott was convincing him that he was getting horrible advice and being treated like a piece of meat. I wasn’t in the doctor’s office when they discussed Bill’s injuries, but I’m sure Bill could have said, no, I’m not playing until I’m 100 percent, and I won’t let you inject me with painkillers. But few athletes in the history of sports have been more competitive than Bill. When you’re the best player in the league and your team is counting on you, sitting on the bench isn’t an option.

When Bill finally decided he wanted out of Portland, it’s instructive that he didn’t even attend his farewell press conference and it was Jack Scott who stood before the cameras and microphones and announced the end of the love affair between Portland and its most beloved athlete in history. The same Jack Scott who always refused to stand for the national anthem even though the Blazers always comped him his tickets.

As ugly as it was when Bill jilted Portland—it ranks down there with the fall of Neil Goldschmidt and the blight of downtown following the 2021 riots as nadirs in Portland’s psyche—he redeemed himself 30 years later when he returned to the city and admitted he’d made a mistake, a sign of how much he’d grown.

Bill the Announcer

Bill had a long and successful run as an announcer for basketball games on ESPN, CBS and, in the end, the Pac-12 Network. His announcing style was prone to hyperbole and an unmoored stream of consciousness. He was an acquired taste.

About five years ago, I spent a day with Dave Twardzik, a starting guard on the ‘77 championship team. In many ways, he and Walton were on the opposite ends of the political/cultural spectrum. They didn’t hang out much off the court, but they were absolutely in sync on the court, perfect complements to Ramsay’s fast break style of play and dedication to the game.

I asked Twardzik, an immensely likable guy, what he thought of Walton’s announcing. He paused, considering his answer, then finally replied: “I liked him better when he stuttered.”

Tim Boyle and Kobe Bryant

I first met Tim Boyle, the CEO of Columbia Sportswear, when he bought 50 copies of my book Goat Brothers and invited me to his office to sign copies for his friends. He also put up the money to option the movie rights to Counting Coup, a book I wrote about a young Crow Indian girl trying to lead her high school team to the Montana state basketball championship while battling all the dysfunction of a reservation.

In brainstorming how to get it produced, Tim came up with the idea of Kobe Bryant. Recently retired from his Hall of Fame career with the Lakers, Bryant had launched a movie production company, winning an Oscar in his first year in the business. And he was an avid supporter of women’s basketball.

Tim and I didn’t know how to contact Kobe directly, so it was his idea to see if Walton could get us an introduction. Walton’s son Luke had been a teammate of Kobe’s, as well as his coach.

But when Tim contacted Bill about getting in touch with Kobe, Bill said that he really didn’t know him well enough to approach him on a movie deal. We were surprised that these two all-time great superstars weren’t chums. Bill said he’d see if he could find another entrée. Bryant died a couple of days later in a helicopter crash on his way to one of his daughter’s games.

But Bill still wanted to help. He connected us with a Hollywood agent. I appreciated his earnestness. But nothing came of the contact.

The Luckiest Guy in the World

The volume of newspaper clippings, interviews and game footage on Walton is enough to fill the Rose Festival Fun Center, before it was called CityFair. But for my money, the best insight into who he was as a person is the 2023 ESPN 30 for 30 documentary The Luckiest Guy in the World. The filmmaker was Steve James, an award-winning documentarian with over 30 films to his credit, including Hoop Dreams. Walton agreed to give him full access, with just a couple of caveats: James couldn’t interview Susan, the mother of Bill’s four sons, and Bill would get to view footage before the film’s release. I was honored to be interviewed for the film.

In addition to archival footage of Bill in high school and college, James devotes significant time to a thorough investigation of Bill’s injuries when he was with the Blazers, including X-rays, medical analysis and interviews. Any lingering suspicion that Walton was malingering during that time are completely laid to rest. The four-part series is an homage to Walton’s courage and grit…and, of course, his zest for life.

But for reasons we will never know, Bill didn’t see it that way. In the final episode, we see him questioning whether James secretly believed the persistent rumors that Bill was malingering. It was as if Bill saw a different movie and reverted back to the end of his Blazer days when paranoia about people not having his best interests at heart prevailed.

Not content to doubt only James, in an off-camera moment, Walton added this: “And Larry Colton doesn’t believe I was really hurt either.”

Bill’s not here anymore, but if his amazing spirit and the humanitarian force that brightened our days are somehow floating close by, I’d like him to know that I believed him 150 percent, flaws and all, and although I probably can’t compete for the title of luckiest guy in the world, I’ll settle for being the luckiest guy in Portland, thanks to getting to hang with Bill during the city’s unforgettable days of Rip City romance.

And Bill, you can stop pedaling now. Nobody’s ever going to catch you. It’s all downhill from here.

GO: Larry Colton will attend a screening of Fast Break at the Hollywood Theatre, 4122 NE Sandy Blvd., 503-493-1128, hollywoodtheatre.org. 7:30 pm Wednesday, June 19. $10-$12.