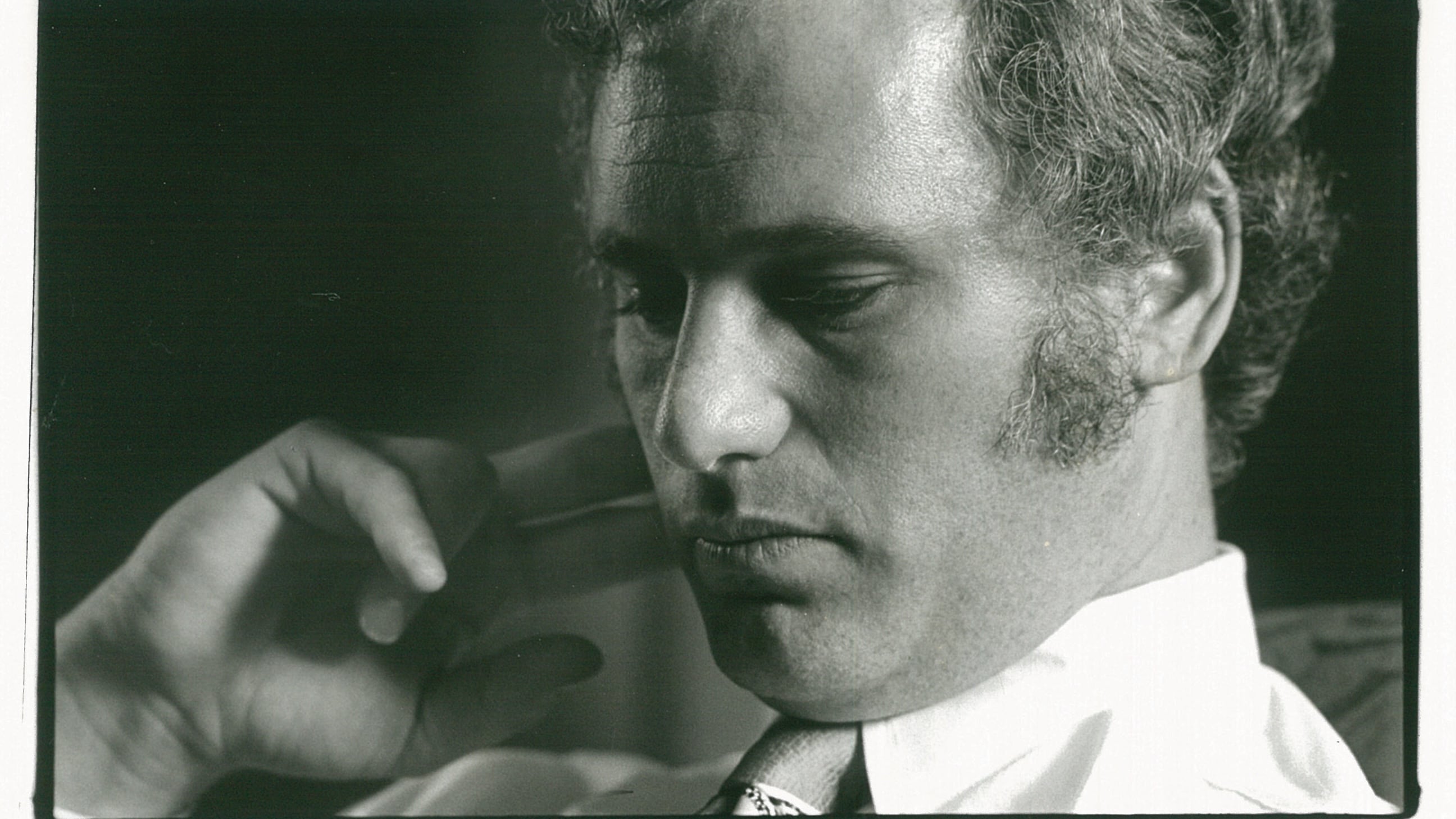

Former Portland Mayor and Oregon Gov. Neil Goldschmidt, who set the city’s course for a generation while repeatedly raping a teenager, has died just short of his 84th birthday. The Oregonian first reported his death.

Goldschmidt, 83, a Eugene native, first won election to Portland City Council in 1970, when he worked as a legal aid lawyer. In 1973, he became the youngest big city mayor in the U.S. at age 33 and would hold that position for six years.

During Goldschmidt‘s tenure at City Hall, he led Portland’s transformation from a conservative city dominated by business leaders to a cradle of progressive ideas, none bigger than blocking the proposed Mount Hood Freeway between the Marquam Bridge and Interstate 205. Goldschmidt and his allies convinced the feds they should instead use the money to launch a new light rail system.

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter pulled Goldschmidt away from Portland, naming him secretary of transportation—a cabinet official not yet 40. After Carter lost his bid for reelection in 1980, Goldschmidt returned to Oregon, taking a senior position at Nike.

In 1986, he returned to politics, however, defeating Norma Paulus in a hotly contested governor’s race—and began a streak of Democratic victories in governor’s races unbroken since then. As governor, Goldschmidt presided over the transition of Oregon from a resource-based extraction economy to a technology and sportswear hub.

He stunned the Oregon political establishment by forgoing a reelection bid in 1990. Although he was going through a divorce, Goldschmidt never gave a satisfactory explanation for why he’d walk away from Mahonia Hall at the age of 49. That decision brought an end to a political career that The Washington Post’s David Broder—then the paper‘s top political columnist—speculated could have led him to a place on a presidential ticket.

Instead, Goldschmidt opened a private consulting firm, offering advice and assistance to the late Paul Allen (co-founder of Microsoft and owner of the Portland Trail Blazers) and Bechtel Corp., among others. He grew wealthy after leaving politics, serving on the board of a credit card company owned by a political associate.

Goldschmidt maintained a powerful position in his consulting practice. Many of the state’s leaders, both in government and the private sector, either got their jobs through their association with him or sought his counsel. In 2004, the state’s largest utility, Portland General Electric, was on the auction block because its then-owner, Enron, had gone bankrupt. The Texas Pacific Group, a highly successful private equity firm, hoped to buy PGE but recognized it would be politically unpopular for a leveraged buyout firm to acquire a company so central to the state’s economy and its ratepayers.

Texas Pacific hired Goldschmidt and a small group of allies to lead the buyout, reasoning that his unmatched political influence would eliminate any opposition. As WW reported on the deal, which entailed a long approval process in front of the Oregon Public Utility Commission, former state Sen. Vicki Walker (D-Eugene) passed along a tip: Goldschmidt might have been involved in a legal settlement years earlier related to a young babysitter.

It seemed unlikely—Goldschmidt had been the most highly covered politician of his era, would have been targeted by opponents in his political campaigns, and would have undergone a thorough FBI background check before becoming Carter’s transportation secretary.

But the unlikely turned out to be true. During his tenure as mayor, Goldschmidt regularly sexually assaulted a girl named Elizabeth Dunham, beginning when she was 13 or 14 and continuing for many years. That constituted rape, although Goldschmidt was never charged with a crime.

Related: The 30-Year Secret.

Dunham, a promising student at St. Mary’s High School when the abuse began, suffered a series of legal and mental health challenges and died at age 49 in 2011. (WW did not name her until after her death.)

Related: Elizabeth Lynn Dunham: May 12, 1961-Jan. 16, 2011.

After nearly three months of reporting, WW approached Goldschmidt and his victim in the spring of 2004, seeking interviews about what had happened beginning in the 1970s. Dunham, then living in Las Vegas, had negotiated a $350,000 settlement with Goldschmidt in 1994. That settlement bought her silence, and she denied any abuse. Goldschmidt declined to talk. Instead, he began resigning his positions, which included serving as chairman of the Oregon State Board of Higher Education, a position to which then-Gov. Ted Kulongoski, one of his many protégés, named him.

WW broke the news of Goldschmidt’s abuse of Dunham in 2004. The story was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting the following year.

After WW published its account of the years of abuse, Goldschmidt receded from public life, safe from prosecution because the statute of limitations had run out, but no longer a person of influence. For many of his allies, Goldschmidt’s downfall was a bitter pill to swallow because they had benefited from their association with him. In 2004, many leaders initially thought Goldschmidt could ride out the storm.

Reaction today was more pointed. “Neil Goldschmidt’s abuse of a young girl destroyed her life, a horrific act that should make any other discussion of his political career moot,” U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) said. “The best response to this news would be to contribute to organizations dedicated to preventing sexual abuse, such as the Oregon Association for the Treatment and Prevention of Sexual Abuse.”

Goldschmidt spent the final 20 years of his life living quietly in Southwest Portland, a stone’s throw from the Multnomah Athletic Club, where he held court for years prior to the disclosure of his crimes. The MAC, like the Oregon State Bar, no longer wanted him as a member after WW’s story ran.

Goldschmidt died at home of heart failure June 12, his family confirmed, four days short of his 84th birthday.