Ever get the feeling you’ve forgotten something? Maybe the Oregon State Treasury has it.

The treasury has a $1 billion fund of unclaimed money and property. It’s so much money that its accrued interest funds a gift of $30 million or so to Oregon’s schools every year.

Last year alone, the state received nearly $140 million in things Oregonians left behind.

Most of that is lost cash: paychecks from employers, stock dividends from banks, payouts from insurance companies.

Go look, right now, on the treasury’s webpage. There’s a decent chance you have a forgotten buck owed to you. One in seven Oregonians do.

On average, the amount forgotten is around $200, officials say. But every week, someone gets six figures—for some, a life-altering sum. One recent recipient, a woman in her 80s, sent her grandson to college.

Every state in the country has an agency whose responsibility it is to reunite citizens with their cash. But in 2020, Oregon became one of the first states in the nation to try to identify the owner of unclaimed property and send out checks for money that has not been claimed—without being asked. The program, begun under State Treasurer Tobias Read, has returned more than $17 million.

But the state’s hoard of unclaimed property isn’t just cash, or some close form of it such as stocks or bonds. (Cryptocurrency is a growing state concern.)

The state also has your stuff. That’s because banks send the treasury the contents of abandoned safe deposit boxes, around 700 each year, which the treasury stores in case the owner shows up to collect it.

The same is true of the belongings of people who die without heirs.

When the state learns from law enforcement, or anyone else for that matter, that someone has died and nobody can find their next of kin, the treasury employs a specialized strike force—the Estates Field Team—to go retrieve personal property before it’s stolen or disappears.

Hundreds of times every year, the state needs to step in, gather assets from estates, and try to find heirs, either from a will or by tracing next of kin.

According to Claudia Ciobanu, director of the treasury’s trust property division, about 50 cases each year take months, sometimes even years, to settle.

Every few years, the state holds an auction to convert valuables into cash. Proceeds from auctioned safe deposit boxes or forgotten checks can be claimed forever. Heirs of the deceased, however, have only a decade to claim property from estates before it’s permanently transferred to the Common School Fund.

In the meantime, the treasury has entire rooms dedicated to preserving these objects, whose owners have disappeared or died.

The goods pile up in a pair of vaults in the bowels of the treasury’s brand-new Salem headquarters. It was built in 2022 to withstand a magnitude 9.0 earthquake. Inside, behind a locked door, are rows of fireproof safes, where property awaits its rightful owner to claim it.

The vault is a museum of oddities, full of mysteries. The items include ancient Egyptian artifacts left behind by a penniless Astorian antique dealer. A 4,000-year-old tax receipt, paid in bushels of barley, etched on a cuneiform tablet from what’s now Iraq. And a fossilized bat.

Twelve State Treasury employees have the job of finding their rightful owners.

“We geek out on this,” says Ciobanu, a steely-eyed former state auditor who now leads the division. Her team includes ex-Marines and a former computer science professor.

On a recent afternoon, WW visited the treasury vaults that contain dead Oregonians’ treasures. In the following days, our reporters made a few phone calls of our own, trying to suss out the stories of the people whose property now sits in the vaults.

On the following pages are the stories of these objects, and the owners who left them behind.

Item: Gilded cartonnage mummy mask from the Ptolemaic dynasty

Last known owner: Roger Meyer

Estimated value: $7,000 to $10,000

Date obtained by the treasury: 2019

The story behind it: Meyer was living off food stamps at an Oregon hotel when he got a certified letter postmarked from Nebraska. It told him he was a rich man.

A storage container in Lincoln full of ancient artifacts, appraised at $200,000, had been turned over by a bank to state officials, who determined Meyer was the rightful owner. It’s not clear exactly when this happened, but the curious incident was covered by a Nebraska newspaper in 2009.

Meyer was excited. Before falling on hard times, officials believe, he’d once run an antique store. (His phone was registered to a company called “Roger’s Treasurechest,” although WW couldn’t locate it in historical records.) He’d forgotten about the box, assuming it had been long lost after he stopped making payments to the bank. He gave detailed instructions on how to send the contents west, according to a story in the Lincoln Journal Star.

And that’s how this Egyptian funeral mask ended up at an Astoria apartment building, along with an ancient Phoenician dagger and several Roman clay pots dating back to the first century CE. Despite his poverty, Meyer never sold the artifacts. He died in 2019, deep in medical debt, with the treasures piling up in a cluttered Astoria apartment. The state was called in after the landlord reported the unit abandoned.

As Nebraska had, Oregon officials sent certified letters to family members. No one responded.

Now, the treasury must figure out what to do with the collection. “We can’t throw it away—it has value,” Ciobanu says. (Not everything. One pot, officials believe, is a cheap forgery.) They’re waiting for a Willamette University professor to help appraise the items this summer, and then it’s off to auction.

Proceeds will go first to repay Meyer’s debts. The rest, at least if no heirs redeem it within 10 years, will help fund Oregon schools.

Item: Leather book with a lock of hair

Last known owner: Shawn Gant

Estimated value: Sentimental

Date obtained by the treasury: December 2023

The story behind it: Gant died on an 85-acre farm in Coos Bay last December. When law enforcement found him, they believed he’d been dead for weeks.

When the estates team first arrived at the property, 78 head of cattle had wandered out of a barn and spilled outside a fence.

“We tried to corral them as best we could,” says Greg Goller, head of the estates team and a former police detective. “You get a stick, like you see on TV.”

Goller knew a rancher, who trucked in five 500-pound bales of hay to feed the starving cows. Over the next two weeks, the team sold 78 unbranded and unvaccinated cattle for a combined $20,000.

Law enforcement told the treasury that items had gone missing from the property and neighbors had reported trespassers on the farm. By the treasury’s reckoning, after cross-referencing with Oregon DMV records and law enforcement, two Toyota pickups were gone, as was a boat, two motorcycles, and some tractors. Gun safes had gone missing, too.

“The house was completely ransacked,” Goller recalls. “The drawers were open, cabinets were open.”

On the estate team’s second visit, according to Goller, a middle-aged couple walked onto the property and said they had Gant’s will. Their names were Andy and Nicole Sharp, and they appear to be avid mushroom hunters. Andy Sharp told the estates team that Gant had entrusted all of his property to Nicole Sharp after a six-month friendship.

The Oregon State Treasury was appointed special administrator of Gant’s estate by a Coos County circuit judge in January. That same month, one of Gant’s cousins challenged the validity of the will, writing in case filings that he believed it to be “ineffective in full or part.”

In a March 8 filing, the attorney for one of Gant’s relatives wrote that the Coos County Sheriff’s Office had named the Sharps as “persons of interest” in a criminal investigation involving Gant’s property and “withdrawals from financial institutions of Mr. Gant’s.” Goller says associates of the Sharps’ had been found squatting in a small, run-down home Gant owned in town.

The Sharps did not respond to requests for comment.

The treasury will hold on to Gant’s stuff until the court determines who has legal rights to it. As special administrator, the treasury has listed the farmhouse and received several offers above the asking price of $850,000.

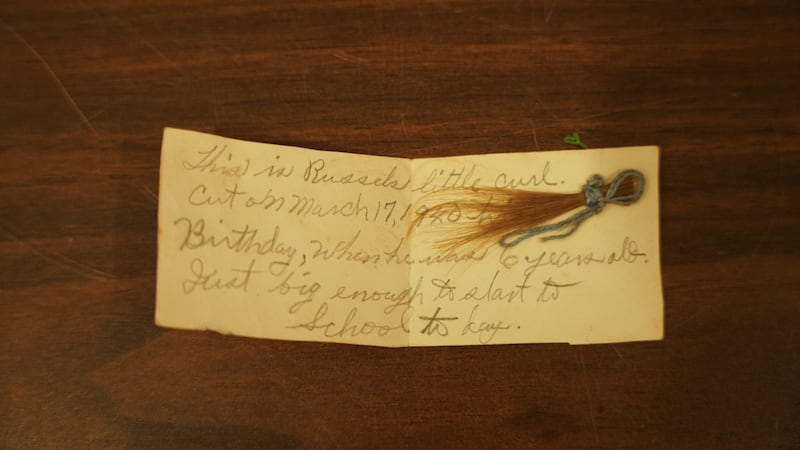

Among the objects now in the vault: a leatherbound book that includes notes that Gant’s grandmother wrote to his father. A lock of Gant’s father’s hair from when he was a child is tied to a scrap of browned paper with a piece of blue string. The scrap reads: “This is Russell’s little curl. Cut on March 17, 1940, his birthday when he was 6 years old.”

In another letter, Russell Gant writes to his mother about his wife, Anne, pregnant at the time: “Anne looks like she is going to topple over any moment…I reckon that it will be a right smart of a kid, I do.”

Deborah Mayhew, Gant’s cousin, says that’s true: Gant was smart as a whip. He was a guard at Folsom State Prison for years before retiring early on disability and moving to Coos Bay to find some peace, Mayhew says. When Gant’s mother died, he inherited enough money to buy the ranch. He became a bit of a recluse after that, she says.

“He had a very complicated relationship with his mother, so when she died, that enabled him to break free of that,” Mayhew says. “He could finally do what he wanted.”

Item: Fossilized bat

Last known owner: Scott Brandow

Estimated value: $26,500

Date obtained by the treasury: 2023

The story behind it: State officials know almost nothing about Milton “Scott” Brandow.

He purchased a safe deposit box in 1994, inserted a collection of curios, and left them behind forever.

After he died, his wife opened the box, likely searching for a will, treasury officials say. But she did not claim its treasures, which include a fossilized bat dating from the Eocene epoch and a small Sumerian cuneiform tablet originally purchased from a New York antique store.

A death certificate found inside the box identifies its owner as Brandow, who died in 2011 and, according to an obituary published in the Eugene Register-Guard, was a man of diverse interests. After earning a degree in finance from the University of Oregon, “he worked as an accounting instructor, small-business and financial consultant, computer programmer, journeyman swordmaker, theater tech, voice actor and author.”

And, apparently, an avid collector of antiquities.

The cuneiform tablet was a tax receipt: 12,000 quarts of barley delivered to a temple in what is now northwestern Iraq. It dates from the third dynasty of Ur, the treasury says, around 2000 BCE.

The bat was originally collected from a famously fossil-rich quarry in Germany, the Messel pit, preserved in shale. Treasury officials have identified it as a Palaeochiropteryx: a small, extinct genus of bat that bears a strong resemblance to its modern descendants and is commonly found in the Messel.

Brandow’s safe deposit box contained a lot more: counterfeit Confederate currency, a vast coin collection, and ancient Samarian cylindrical wax seals.

The treasury plans to give his family a few more years to claim the items before auctioning them off. “It’s very special stuff,” Ciobanu explains.

Item: Purple Heart awarded to William R. Reeves for service in World War II

Last known owner: William Roney, Bruce Roney, and Barbara Roney

Estimated value: Unknown

Date obtained by the treasury: 2015

The story behind it: Reeves earned the Purple Heart, according to family lore, after he was shot in the foot while jumping into a foxhole to save another soldier during the war.

Over a half century later, the medal turned up in the family’s abandoned safe deposit box. After the box ran up hundreds of dollars in unpaid fees, Bank of America turned it over to the treasury.

A Veterans Administration receipt in the box indicated the award wasn’t an original, it was a copy requested by his family.

The treasury has been in contact with several family members over the years, offering to return it with the right paperwork. No one has yet taken it up on the offer.

Jeffrey Roney, Reeve’s grandson, was one of the family members who attempted to retrieve the medal after the treasury contacted him five years ago. “You’re the 25th person to call,” he told WW.

He says he believed his grandfather earned the medal during the invasion of Normandy. Reeves died in 2005.

But he’s given up retrieving it. “The hoops we had to jump through were ridiculous—we chose not to take that further,’ he says. “We know our grandfather was a hero. We don’t need a medal to show that.”

Item: World War I military record of Ira Ralph Arney

Last known owner: Betty A. Singleterry

Estimated value: Unknown

Date obtained by the treasury: 2016

The story behind it: The treasury obtained Arney’s record after it was found in an abandoned safe deposit box belonging to Singleterry. She died in 1966, and the treasury has been unable to locate any heirs.

Arney served on warships for the U.S. Navy for more than 30 years, beginning in 1908, and climbed to the rank of chief petty officer before being discharged in 1939. The record, written on wax paper to withstand life on a ship, was the equivalent of a modern-day military identification card.

“We can’t bring ourselves to dispose of it because it’s so unique,” says Carolyn Harris, audit and holder services manager.

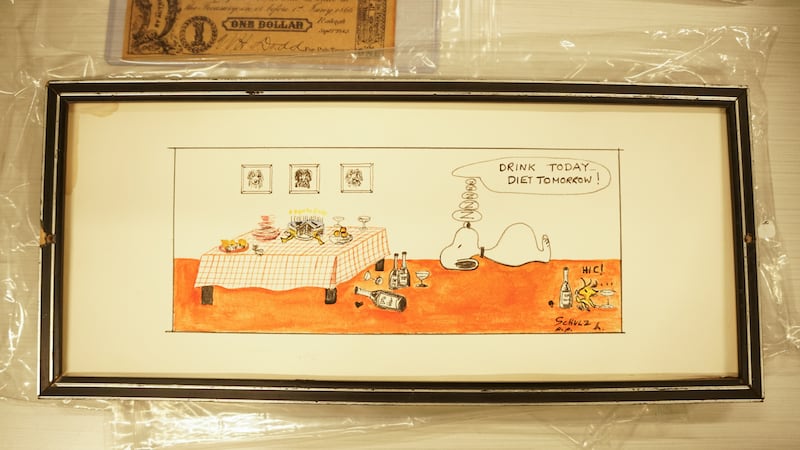

Item: Original Charles Schulz cartoon, circa 1970s

Last known owner: Christopher A. Pompei

Estimated value: $5,000

Date obtained by the treasury: 2019

The story behind it: After the cartoon showed up in an abandoned safe deposit box, someone called the treasury to claim it—but never followed up with the necessary documentation to prove ownership.

Item: Hand-colored photograph

Last known owner: Jane Marnchianes

Estimated value: $50–$100

Date obtained by the treasury: 2022

The story behind it: There is a sweetness to the small staff’s loyalty to certain objects that might hold sentimental value, even if they look better suited for the dumpster. Like Jane Marnchianes’ weathered, hand-painted oval photograph of an unknown man.

Marnchianes died at 83 in 2022. She appeared particularly passionate about legislation related to end-of-life care. In fact, Oregon business records show, she ran a mutual benefit nonprofit for a few years under the name “Oregonians for Patients’ Rights,” and she regularly testified about end-of-life decision-making.

The State Treasury found no living relatives for Marnchianes in the U.S. Her family was traced to Greece, but “due to language barrier and limited availability records, professional genealogists were unable to locate relatives,” the treasury team says.

The estates team found the painted photo in Marnchianes’ modest North Portland home in the Kenton neighborhood. It’s drab but has a bright pink bathtub.

Kay Schneider lived across from Marnchianes and her sister, Helene, for decades. Neither of the sisters ever married, Schneider recalls, and the sisters’ parents had lived with them in that house until they both died.

“Unfortunately, I don’t have anything nice to say about her. She was very paranoid, and she thought everyone was stealing from her,” Schneider recalls. “She blamed the nursing home for killing her sister, things like that.” Marnchianes did, however, always bring a store-bought apple pie to Thanksgiving. “She was gracious that way.”

Other neighbors found her to be lonely, stubborn and fearful of new things and people. Paul Brakebush, who drove Marnchianes to and from the grocery store and doctor appointments for 20 years in his cab, sometimes wonders if he could have done more to broaden her world.

He can only recall one change in her habits over that time: After expressing deep skepticism about eating a Filet-O-Fish sandwich from McDonald’s, she developed a craving. “She went crazy for them for a while. I thought, oh my God, I’ve got her hooked on McDonald’s.”

The treasury sold Marnchianes’ home for $360,000 in September 2023 and placed the money in trust for heirs to claim it. If no heir steps forward within 10 years, it goes into the Common School Fund.

Item: Diamond-studded yellow gold Rolex

Last known owner: Geoffrey P. Schultze

Estimated value: $13,950, if authentic

Date obtained by the treasury: 2022

The story behind it: Left in an abandoned safe deposit box. No potential owners have come forward.

Item: The military dependent ID of 10-year-old Jordan Deemer

Last known owner: Lloyd A. Barnes

Estimated value: $0

Date obtained by the treasury: 2019

The story behind it: On a recent Wednesday morning, as WW reporters watched, treasury employees Carolyn Harris and Faith Kerskey ripped open a plastic shipping bag, emptying its contents into a gray sorting box. It’s one of 2,300 bags, filled with possessions from bank safe deposit boxes, that the State Treasury has in its possession but has not yet opened.

The state receives the contents of around 700 new boxes a year, and doesn’t have the staff to pick through them all.

This particular bag, containing the items of a Portland man named Lloyd Barnes, the state has held since 2019.

Sometimes the contents of a box tell a fractured story of its owner’s life: joys, sorrows, bodily pain. Other times, the unclaimed property team doesn’t know what to make of what’s inside.

Barnes’ box included some memorabilia: a tangle of cheap costume jewelry, a handmade Shrinky Dinks ornament, a Little League pin, a small brown pocketknife. Holding two painted wooden eggs, Harris declared them tacky. Ciobanu thought they were so nice, she’d even consider putting them in her home.

But the rest of the items skewed tragic.

There was a military dependent ID for Jordan Deemer, Barnes’ now-27-year-old son. A Fred Meyer receipt from 2018 for mostly freezer meals, beef stroganoff and Franz bread. And three empty painkiller pill bottles: oxycodone, gabapentin and morphine. The box also held a flyer for end-of-life decisions.

“He was probably in a lot of pain,” Harris said.

His son, Jordan Deemer, confirmed that. For as long as he could remember, his dad was addicted to pain pills. His father served in the U.S. Army for four years and lived off disability checks after two back surgeries. He died in 2021 of a fentanyl overdose, Deemer said.

“He used to give me morphine for headaches starting when I was 16,” Deemer told WW. “That’s probably not what you want in your story. But that’s life sometimes.”

Deemer said of Barnes’ fatherhood: “He tried.”

In Barnes’ box was a weathered photo, looked to be taken in the 1990s, of a smiling young woman sitting on a picnic table. She’s wearing high-waisted jeans and a white T-shirt.

It was a picture of Deemer’s mom. He’d never seen it before.