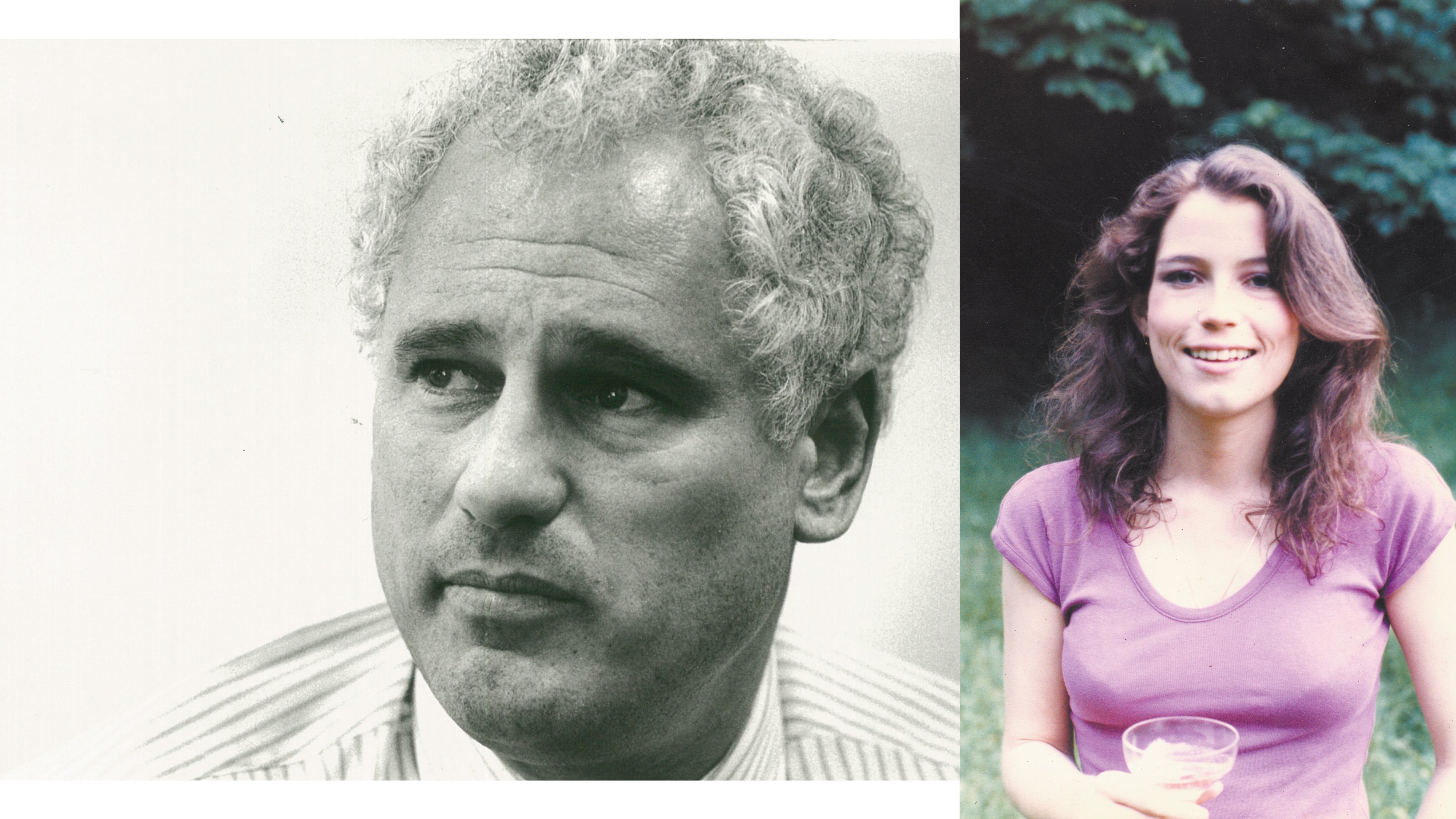

Vicki Walker had just left a June 12 meeting at Ross Island Sand & Gravel’s office on the east bank of the Willamette River when she learned that former Portland mayor and Oregon governor Neil Goldschmidt had died at 83.

Walker, 68, a former state senator who now leads the Oregon Department of State Lands, says she remained for a while in her car, processing the death of a man whose dark secret she, more than anyone, helped expose.

“I just sat there for a few minutes,” Walker says. “I wasn’t really in a place where I could feel anything.”

Walker first met Goldschmidt in 2003, more than a decade after he left Mahonia Hall for high-placed consulting work. She, like every Democrat in Oregon politics, knew well the position he occupied in political and business circles. “He was the king,” Walker says. “Anybody who wanted to run for higher office in Oregon had to go kiss his ring.”

Goldschmidt first won a position on the Portland City Council in 1970. In 1973, he became the youngest big-city mayor in the U.S. at age 33 and held that position for six years.

During Goldschmidt’s tenure at City Hall, he led Portland’s transformation from a conservative city dominated by business leaders to a cradle of progressive ideas, none bigger than blocking the proposed Mount Hood Freeway between the Marquam Bridge and Interstate 205. Goldschmidt and his allies convinced the feds they should instead use the money to launch a new light rail system. After a stint as President Jimmy Carter’s secretary of transportation, Goldschmidt worked as a senior Nike executive and then served as governor from 1987 to 1991.

In 2003, Walker was a newly minted state senator, representing Goldschmidt’s hometown, Eugene, in the Legislature. Like Goldschmidt, she’d graduated from the University of Oregon, and she’d voted for him in the 1986 gubernatorial election, but she’d never met him until she had the temerity to question his lucrative consulting contract—$40,000 a month—with the state-owned workers’ compensation firm, SAIF Corp.

Walker demanded answers in contentious Senate hearings, and Goldschmidt responded by taking a shot at her in the media. As a private consultant, Goldschmidt brokered big deals—such as Bechtel Enterprises’ 2001 construction of light rail to Portland International Airport and Weyerhaeuser’s controversial 2002 acquisition of Oregon’s largest timber company, Willamette Industries. He wasn’t accustomed to criticism, let alone from a relatively junior lawmaker.

Senate President Peter Courtney (D-Salem) arranged a meeting. But in Walker’s recollection, it didn’t work because Goldschmidt stood by critical remarks he’d made in the newspaper. “I told him to go to hell,” she recalls.

Not long after that meeting, Portland Tribune columnist Phil Stanford shared with Walker a Washington County court document Stanford thought might be part of a scandalous chapter in Goldschmidt’s past—but neither he nor Walker could prove what happened.

Walker shared the document with WW, and after an investigation, this paper published the story of Goldschmidt’s repeated rape for years of a teenage girl (“The 30-Year Secret,” May 5, 2004).

Elizabeth Lynn Dunham died in 2011, after more than half a lifetime of mental torment and struggles with addiction. Now Goldschmidt is dead, too. The last remaining people with ties to his abuse are the dozens who learned about it during his three decades in power—and a couple who spoke out.

Walker says her original objection to Goldschmidt was philosophical: She thought the workers’ comp reforms he orchestrated as governor unbalanced the system. “Injured workers were just getting screwed,” Walker says. Their differences, however, went far deeper: Walker came to see Goldschmidt as a more refined version of her father, who, along with two of his brothers, sexually abused her when she was a child. “My father was a horrible man,” Walker says.

Now, the man with whose name hers will forever be linked is gone. Walker says she feels empathy for Goldschmidt’s family, but not for him.

To Walker, Goldschmidt’s escape from prosecution—the statute of limitations expired long before WW broke the news of his sexual abuse of Dunham—allowed him to live out his life comfortably amid the wealth his consulting business brought him.

“He never really paid his dues for what he did. He had his winery in France and some friends,” Walker says. “That’s not exactly purgatory.”

Alone among the many subordinates, friends and associates who knew Goldschmidt’s secret over three decades, Fred Leonhardt stepped forward to tell the truth.

In 2003, Goldschmidt returned to the public stage in two important ways for the first time since mysteriously leaving the governor’s office in 1991 after a single term.

One of his many protégés, then-Gov. Ted Kulongoski, named him chairman of the Oregon State Board of Higher Education with the assignment to reform the system. And the Texas Pacific Group, a fabulously successful leveraged buyout firm, hired Goldschmidt to help it buy Portland General Electric, then in the possession of Enron, the bankrupt energy trading firm. Both Kulongoski and TPG hoped to leverage Goldschmidt’s unmatched political influence.

Leonhardt, 72, had served as Goldschmidt’s speechwriter when Goldschmidt was governor. He first heard stories of Goldschmidt raping Dunham when he worked in the governor’s office. He says he’d sworn to himself that if his old boss ever sought to influence public policy again, he’d blow the whistle.

In late 2003, he did just that, sharing with The Oregonian a detailed narrative of Goldschmidt’s crimes, who knew about them, and how they’d benefited. The daily, as its editors have acknowledged, failed to act. (Its first story was a sympathetic interview with Goldschmidt, on the eve of WW’s story, in which he offered a sanitized admission of his misdeeds.) After WW published its cover story in May 2004, Leonhardt again shared what he knew, contributing information for subsequent follow-up stories (“Who Knew,” WW, Dec. 14, 2004).

Leonhardt has argued persuasively that many people in Goldschmidt’s orbit had heard about what he’d done to Dunham. A onetime straight-A student at St. Mary’s Academy, Dunham dropped out of high school her sophomore year and later suffered a brutal rape at the hands of a stranger and a variety of other challenges before dying at age 49 (“Elizabeth Lynn Dunham,” WW, Feb. 2, 2011).

“In a way, it feels like an ending,” Leonhardt says of Goldschmidt’s death. “But what still weighs on me is this whole notion of who knew.”

For Leonhardt, being a truth-teller has proven lonely and left him estranged from what he says was a close-knit group of Goldschmidt administration advisers. “None of my former colleagues has ever said ‘you had to do it’ or ‘way to go’ or whatever,” Leonhardt says. “We lost just about every friend we ever had in government or politics,” he says of himself and his late wife.

Goldschmidt’s death caused Leonhardt to reflect on the past two decades, when many of his old friends rose—Kulongoski served two terms in Mahonia Hall, Goldschmidt gubernatorial spokesman Gregg Kantor became CEO of NW Natural—while he sat in front of his keyboard, a pariah. (Kulongoski has denied knowing Goldschmidt’s secret; Kantor says he heard but didn’t believe the rumors.)

“It bothers me that my friends turned out to be what they were,” Leonhardt says, “but I don’t have any regrets.”

Walker says she has no regrets either—except sorrow that it was necessary for people like her and Leonhardt to step forward because nobody stopped Goldschmidt earlier. “I remember voting for him in 1986 and thinking, this guy’s a visionary,” Walker says. “Turns out, he’s not.

“What happens to guys like that is they get consumed by their own power, and little by little, they lose their way,” she adds. “Where I differ from some of the people who were around him is, I think we all have a responsibility to protect children.”