Gov. Tina Kotek has been tight-lipped about her reversals of commutations made by her predecessor, Kate Brown—including how many she’s revoked and why.

But records newly obtained by WW show that Kotek has revoked at least 123 commutations since taking office last year. Most apply to people who committed new crimes or were accused of criminal conduct after their early release.

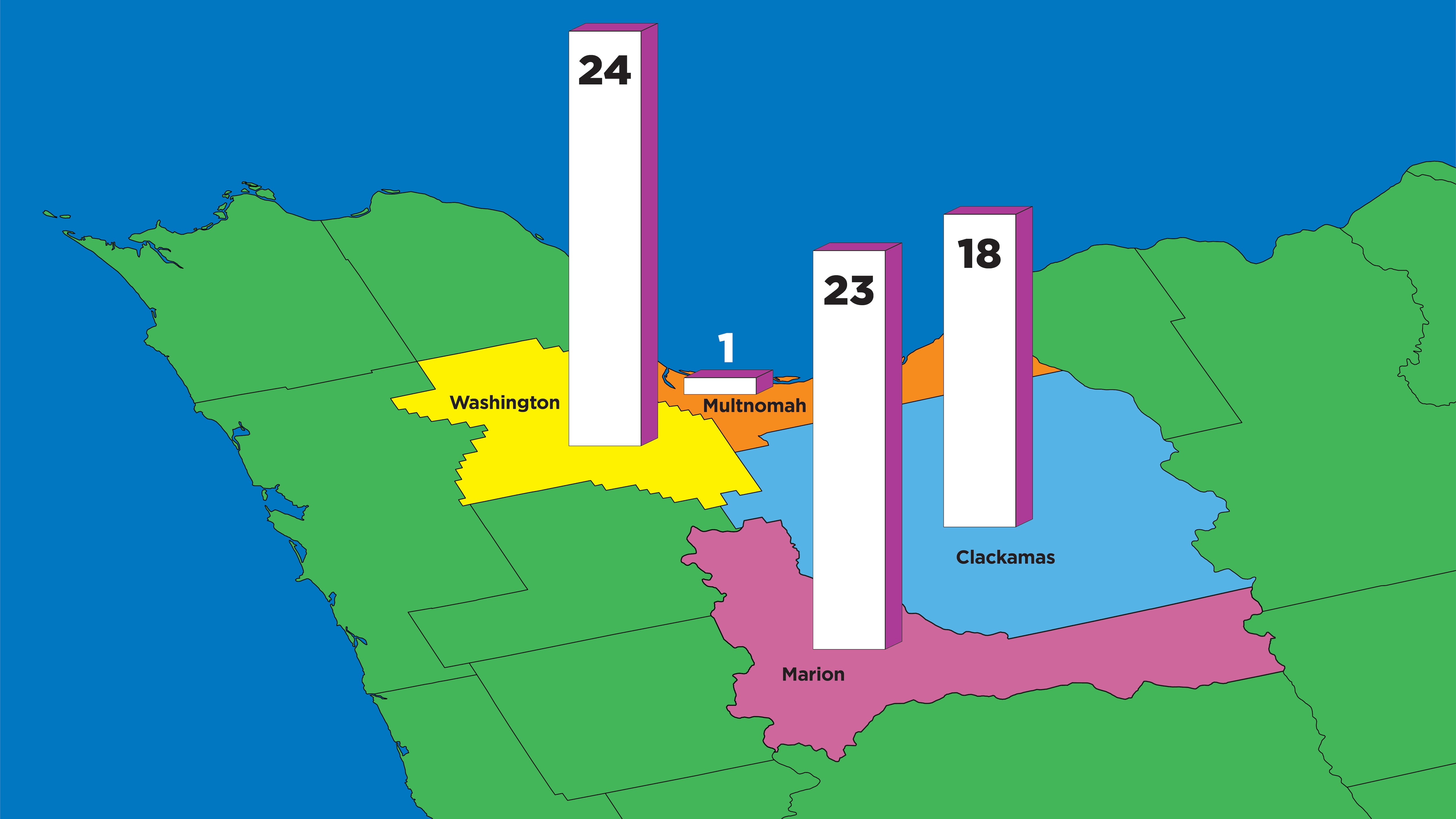

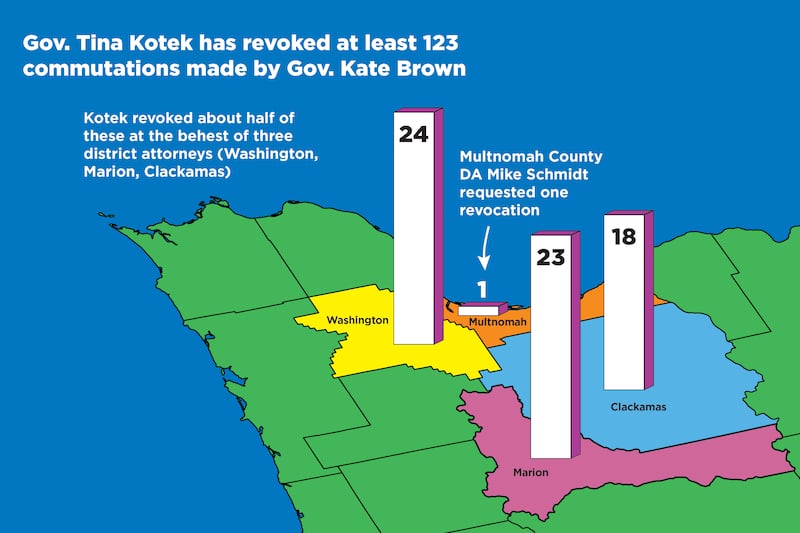

The records also highlight a close alignment between Kotek and district attorneys, who balked at Brown’s many acts of clemency during her two terms as governor and are now playing a key role in Kotek’s policy. Indeed, whether a person landed back behind bars largely depended on where they offended. Washington County District Attorney Kevin Barton successfully sought 24 revocations, while Multnomah County District Attorney Mike Schmidt requested one.

Kotek’s reversals mostly apply to clemencies that Brown issued during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, when she commuted the sentences of almost 1,000 people behind bars to stem the spread of the virus. Most had committed property or drug crimes and were released a few months early.

In her revocation orders, Kotek alleges that more than 120 Oregonians violated the terms of their commutation, mostly by committing a new crime after their early release.

Brown’s commutations typically came with conditions, including an agreement that a person in custody wouldn’t break the law for a few years if released early. In her orders, Kotek says many didn’t uphold their end of the bargain. Her policy is putting people back in prison—or, if they’re already behind bars, keeping them there to serve the remainder of their original sentences.

Concerned defense lawyers say Kotek is locking people back up with no explanation and no notice. In May, judges ruled that Kotek illegally reimprisoned two women who had already completed their sentences. In response, her office walked back at least seven revocations, presumably because they would not survive legal challenges (“No Going Back,” WW, June 5).

Last summer, Kotek asked district attorneys to provide lists of people granted early release by Brown who may have violated the terms of their commutation. Of the more than 120 commutations that Kotek has reversed, more than half were made at the suggestion of just three district attorneys: Kevin Barton in Washington County, Paige Clarkson in Marion County, and John Wentworth in Clackamas County.

Kotek revoked 24 commutations at the request of Barton’s office in Washington County, the most of any. Selling drugs, theft and fleeing police were common violations that led to Kotek’s reversals, according to court records.

Outgoing Multnomah County District Attorney Mike Schmidt requested just one revocation, that of the commutation granted to Brandon Michael Dixon, whom Brown released six years early from his prison term for armed robbery in 2017. Court records show Dixon faces a slew of charges in Multnomah County, including rape and sex abuse.

Lane County didn’t make any suggestions, says chief deputy district attorney Christopher Parosa.

Wentworth, Clackamas County’s DA, says Kotek’s reversals probably apply only to a fraction of the Oregonians who violated the terms of their commutation because most district attorneys didn’t make suggestions. “The number’s low,” he says.

Bobbin Singh, executive director of the Oregon Justice Resource Center, says district attorneys have too much influence over Kotek’s revocations.

“That’s not the governor, then, that’s revoking clemencies—it’s the DAs,” Singh says.

Kotek stands by her process. “I review each revocation request individually, based on the facts of each case and with an aim of keeping our communities safe,” she told WW in a statement. “If I believe someone is violating their conditions of release or supervision and revocation is warranted, I will not hesitate to use my authority and discretion as governor to revoke their commutation.”

Of 950 people released from prison early by Brown due to COVID-19, about 20% were convicted of another crime within two years, according to the Oregon Criminal Justice Commission, a nonpartisan state agency. That’s slightly less than the recidivism rate for people in custody who weren’t released early during that time, the commission found.