When Portland State University criminologist Kelsey Henderson polled cops last year about Measure 110, she heard a consistent gripe.

Overwhelmingly, officers thought the law, which decriminalized possession of small amounts of street drugs, undercut their ability to pressure people into treatment, especially in “drug courts,” which offer a choice between sobriety and hard time.

That was a key criticism of Measure 110 and helped fuel its demise this spring, when state lawmakers reestablished a misdemeanor charge for drug possession. In a recent study, Henderson and two other PSU researchers put a microscope to the idea that participation in drug courts fell off, as police and sheriff’s deputies believed.

What they found: “The narrative that M110 would lead to the demise of drug courts is not supported,” they wrote in their May report.

In fact, drug courts pumped out just as many sober graduates under Measure 110′s short reign as they did before the measure passed. Statewide, defendants participated in drug courts at a steady rate from 2020 through 2023, the study shows.

Measure 110 decriminalized the possession of a small amount of drugs starting in 2021.

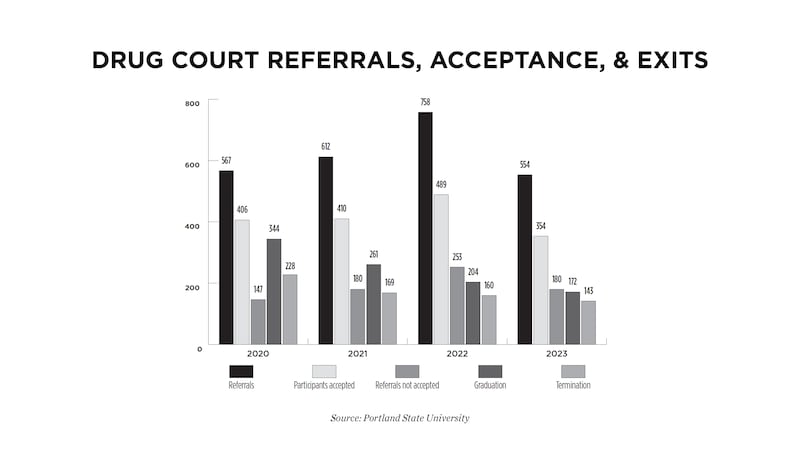

The data show that 567 people were referred to Oregon’s 30 drug courts and 37 “treatment courts” in 2020. Referrals climbed to 758 in 2022 and leveled off at 554 last year. Henderson says that trend continued into May 2024, outside of the report’s time period. Graduations and “terminations”—when someone flunks out of drug court—were also steady, she says (see chart below).

The biggest drags on drug courts were the COVID-19 pandemic and Oregon’s critical shortage of public defenders, not Measure 110, the report says.

Other factors were at work, court administrators and district attorneys tell WW. Drug courts in Oregon and elsewhere had morphed into “specialty courts” as part of a shift in mission: Many that served lower-level offenders now focused on defendants with severe addictions who committed serious crimes, like robbery and assault.

Statewide, many drug courts began serving higher-needs defendants before Measure 110 went into effect, says Phillip Lemman, deputy state court administrator for the Oregon Judicial Department. In other words: Drug courts weren’t serving people facing possession charges, so the law change largely didn’t affect them.

“We don’t believe that Measure 110 itself had a significant impact on drug courts,” Lemman adds.

That was the case in Multnomah County, which closed its drug court in 2020 and set up treatment courts. In the county’s START court (“Success Through Accountability, Restitution and Treatment”), an addicted person who repeatedly commits property crimes has a year to avoid prison by clearing drug tests, committing to treatment, and meeting regularly with a team that includes their judge, attorneys, mentors and counselors. Flunking out can spell prison time, as does refusing to participate.

Henderson, a Ph.D. and associate professor in PSU’s criminology and criminal justice department, is part of a small research team studying Measure 110′s impacts on police departments and courts. She and her colleagues published their study as counties started planning for Oregon’s new era of criminal penalties for drug possession, which go into effect in September. House Bill 4002, passed in March, required counties to set up “deflection” programs to give addicted people several opportunities to choose treatment and sobriety over jail, as drug courts do.

Henderson says it’s unclear what role drug courts will play statewide, but she expects them to be part of the mix.

“They’re certainly a promising pathway,” she says. “There are others. I wouldn’t be surprised if they are part of this recriminalization effort in Oregon for that reason.”