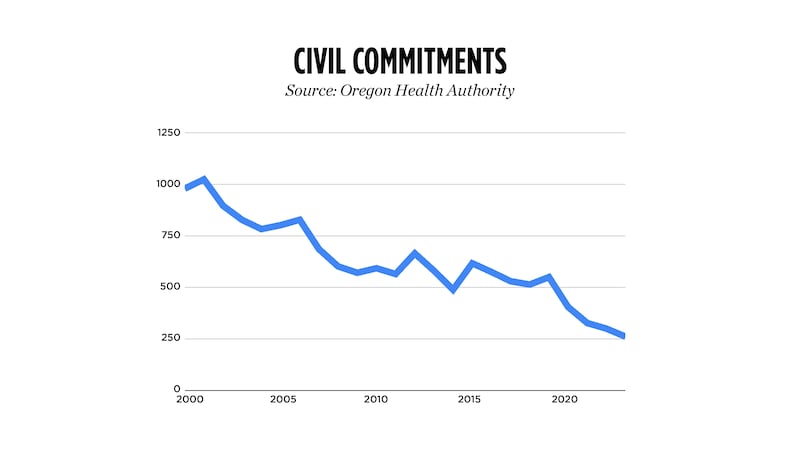

The number of civil commitments, also known as long-term involuntary mental health treatment holds, continues to plummet statewide.

The figure has fallen by half since the pandemic began, marking a rapid acceleration of a decadeslong trend. At the start of the 21st century, there were around 1,000 annually. There have been only 79 so far this year as of May, according to new data compiled by the Oregon Health Authority and presented to local hospital administrators in July.

A civil commitment is the forcible treatment of someone with mental illness. Under Oregon law, it’s permitted only when someone is a “dangerous to self or others” or unable to provide for one’s own “basic personal needs.”

The civil commitment laws on Oregon’s books are similar to those passed in other states. But the Oregon Court of Appeals has shifted courts’ interpretation of those terms over the years to make them increasingly narrow, according to a 2017 analysis of four decades of decisions, by a team of researchers led by Dr. Joseph Bloom of Oregon Health & Science University.

The result, researchers say, is that people with severe untreated mental illness are getting forced into treatment via another means: the criminal justice system.

“They have to commit a crime before we will place somebody in care,” says Chris Bouneff, head of National Alliance on Mental Illness Oregon.

So he’s convened a workgroup and is pushing a proposal to fix it.

Bouneff shared a draft with WW. It provides explicit definitions for the statute’s criteria and allows judges to consider 30 days into the future when weighing how much of a danger someone presents. (The Oregon Court of Appeals has previously said the danger must be in the “near future.”)

He’s currently circulating the draft among lawmakers in hopes of getting it passed during next year’s legislative session. But previous efforts like this one have gone nowhere or had little effect.

For example: The Oregon Judicial Department created a “workgroup” in 2022 to propose solutions. It was supposed to wrap up earlier this year, but has so far come up with few proposals. (A member of the group, Multnomah County Circuit Judge Nan Waller, told WW it had decided to extend deliberations because members had achieved consensus on “a relatively short list of recommendations.”)

And there’s already pushback. Meghan Moyer, head lobbyist for Disability Rights Oregon, which has long been critical of such proposals, says asking courts to evaluate someone’s behavior 30 days in the future is a fool’s errand.

Oregon State Hospital is full and local ERs are overflowing. “Where would people go?” she wonders. “Whose beds should they take?”

Bouneff has an answer. He says the tweaks to the civil commitment law are only part of a larger plan. Also on the table: building more treatment beds for people in crisis.

“It will be coupled with a proposal around services,” he says. “I don’t think anyone else is thinking about this issue in that way.”