Last Christmas Eve, 83-year-old Ki Soon Hyun walked out of her Sandy memory care unit into the freezing night. The following day, police searching the nearby woods found her body.

State officials jumped into action. Regulators shut down the facility, called Mt. Hood Senior Living. The state ombudsman unearthed numerous missed red flags at the home. The governor ordered an audit of the state’s oversight of senior care facilities.

Judging by a WW review of state records, here’s what that audit should find: Oregon’s most vulnerable residents continue to wander out of short-staffed care facilities and into danger.

It’s a national problem. A Washington Post investigation published shortly before Hyun’s death tallied nearly 100 deaths nationwide of residents who wandered away from assisted living facilities, including two in Oregon.

WW has now conducted a similar review in Oregon, expanding its scope to include more recent incidents since Hyun’s death, as well as those that occurred at more tightly regulated nursing homes, where addressing rampant short staffing has become a priority of President Joe Biden.

While our review does not identify any additional deaths, it did find more than a dozen “elopements” from Oregon’s long-term care facilities, including four within a month of Ki Soon Hyun’s death. Sometimes alarms didn’t work or were ignored. In other cases, staff simply weren’t trained to stop residents from taking a walkabout.

In six cases, state inspectors said the facility’s errors resulted in “immediate jeopardy to resident health or safety,” a regulatory red flag that requires an immediate fix.

Most of the elopements identified in the three years of state regulatory files reviewed by WW occurred at nursing homes, which unlike Mt. Hood Senior Living are unlocked, but still tasked with the care and supervision of people with dementia.

Take what happened Jan. 9, days after Hyun’s death: A resident of a Southeast Portland nursing home wandered down a busy street before spending the day riding buses and walking in circles. Temperatures that night fell nearly below freezing. The resident, who had poor decision-making skills and was cognitively impaired, according to evaluators, was found at their original home by a friend the next day.

The 105-bed facility, Cascade Terrace, “failed to ensure safety interventions and supervision were in place,” inspectors concluded.

Elopements like these, Elizabeth Halifax says, just “shouldn’t happen.” She’s a professor at the University of California San Francisco and president-elect of a national advocacy group for long-term care residents.

But they do. “It’s because there’s insufficient staffing,” she explains. The jobs are undesirable: low pay, minimal training, unpleasant working conditions, and high rates of injury.

That’s true, both in Oregon and nearly everywhere else. One national industry survey found 86% of nursing homes, which are largely funded by federal insurance programs, report being moderately to severely short-staffed.

Still, Oregon is different. Unlike most states, it has staffing requirements enshrined in law—and it enforces them. “In most states, citations aren’t happening,” Halifax says.

But WW’s review found facilities are chronically short-staffed anyway. Nearly two-thirds of the state’s 126 nursing homes had been cited for short staffing within the past three years. Nearly a third had been cited in the past year.

This results in poor care, employees say. “There isn’t enough nursing staff to complete everything,” a nurse at Friendship Health Center in Portland told inspectors last September. There were no documented elopements, but inspectors found other reasons to cite the facility. “This is unsafe,” the nurse said.

“There is the common understanding in the human services world that there is a huge caregiver shortage,” says Fred Steele, the state’s long-term care ombudsman. “With that said, it’s a requirement.”

President Joe Biden is pushing nationwide minimum staffing requirements that are, in some ways, even more stringent than Oregon’s current rules.

“Some corporate nursing home owners are taking taxpayer dollars while cutting corners on staffing so they can make big payouts to executives and shareholders,” he wrote in a September editorial published in USA Today. “It’s wrong.”

Data compiled by the facilities’ trade group and submitted to federal regulators shows nearly every Oregon nursing home—97%—currently fails to meet the Biden administration’s proposed regulations.

Both state and federal regulators can already issue fines, however.

Medicare fined Cascade Terrace over $36,000 shortly after inspectors discovered the recent elopement.

But fines only go so far, Halifax says. “The fines are seen by nursing homes as the cost of doing business,” she says. An administrator for Cascade Terrace did not return WW’s request for comment. The Oregon Department of Human Services did not respond to WW’s questions for this story.

Rosie Ward, a spokeswoman for the homes’ lobbying group in Oregon, says more regulation won’t fix the problem. There just aren’t enough people willing to do the job. Without a bigger pipeline of nurses, she says, facilities “will be forced to limit admissions, downsize or, ultimately, close altogether.” That would be disastrous in Oregon, where a shortage of long-term care beds is causing backups in emergency rooms.

Federal and state officials are promising to spend millions of dollars to entice nurses into the field. In the meantime, state inspectors continue to document dangerous elopements. Here’s five that occurred in the past three years:

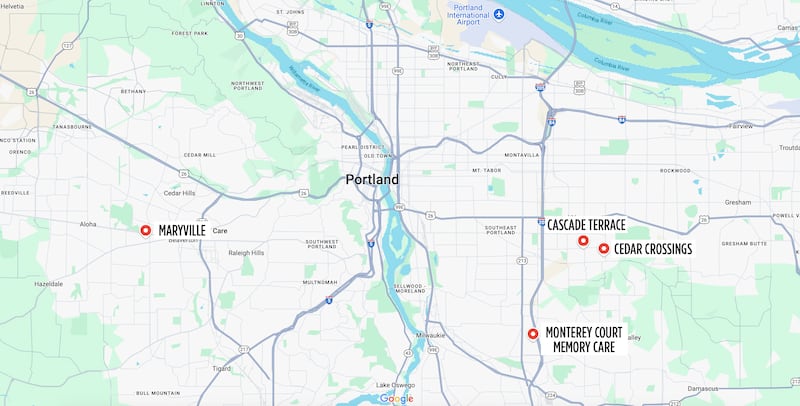

Home: Cedar Crossings

Location: Southeast Portland

Date: June 12, 2024

What happened: Staff called police after the morning nurse failed to locate a resident.

What inspectors say: Cedar Crossings “failed to…modify care plan interventions after ongoing elopement attempts and exit seeking behaviors.”

Home: Cascade Terrace

Location: Southeast Portland

Date: Jan. 9, 2024

What happened: A resident reported having “left the facility, caught the first bus, ended up at the ‘chaotic’ airport, got a ride from a police officer to a public transit station, took a different bus, got off at the wrong station and walked in circles” until locating their apartment.

What inspectors say: “Staff failed to consistently implement one-to-one supervision.”

Home: Maryville

Location: Beaverton

Date: Dec. 3, 2023

What happened: A resident disappeared at 2 am and was later found a mile away at a convenience store.

What inspectors say: Maryville “failed to assess elopement risk and provide supervision….This placed the resident at risk for hypothermia, accidents, and a lack of access to support services.” (A spokesman for the nursing home says staff followed protocols, but he declined to offer specifics.)

Home: Monterey Court Memory Care

Location: Happy Valley

Date: July 18, 2023

What happened: A resident repeatedly left the facility without required supervision, and was once found at a nearby shopping center. After inspectors arrived, the resident was placed under further supervision. The resident then left the building through a window.

What inspectors say: “The failure of the facility to maintain supervision…placed [the resident] at risk and constituted an immediate threat to residents’ health and safety.”

Home: Juniper Canyon Living

Location: Redmond

Date: July 12, 2022

What happened: A resident disappeared in the summer of 2022 before returning nearly three weeks later. The facility conducted no investigation into what had happened. When inspectors arrived in August, the resident was behaving violently toward staff and not being given their medication.

What inspectors say: “The facility’s failure to ensure the preparation, completeness and accuracy of resident’s records placed the resident at risk for future elopement…”