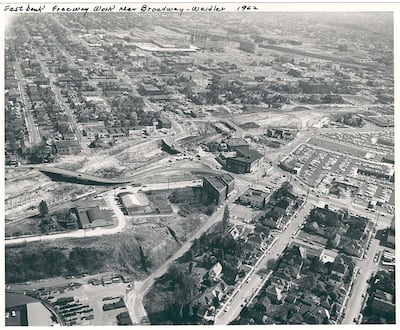

The last time the Oregon Department of Transportation rolled into Albina, the agency arrived with bulldozers and wrecking balls.

That was 60 years ago, when the state highway department gutted Black Portland, razing hundreds of homes and businesses to carve Interstate 5 through the neighborhood where 8 out of 10 Black Portlanders lived. And so began a decadeslong exodus.

Now, ODOT is back, trying to convince the Black community that its proposed Rose Quarter project—widening the freeway through present-day Albina—could be a form of economic reparations, rather than what critics see as a doubling down on traffic, pollution and displacement.

Instead of bulldozers and wrecking balls, ODOT comes this time bearing lucrative contracts and gift cards. Over the past four years, to make its pitch to Black leaders, the agency deployed an army of consultants, none more important than a loquacious preacher from Vancouver, Wash., named Dr. Steven Holt.

Holt’s job: to overcome the skepticism and, at times, outright hostility of people who yearn for the Albina that ODOT tore asunder. He had to sell the agency’s plan to a community that blames the highway department for many sins.

“A lot of people in my district just don’t trust ODOT,” says state Sen. Lew Frederick (D-Portland), who sits on the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Transportation and represents Albina.

A sunny Harley Davidson enthusiast who favors bow ties and crisp pocket squares, Holt, 58, speaks in the lyrical rhythms, rich metaphors and frequent repetitions of a long Sunday sermon. ODOT hired his company to overcome the mistrust Frederick describes.

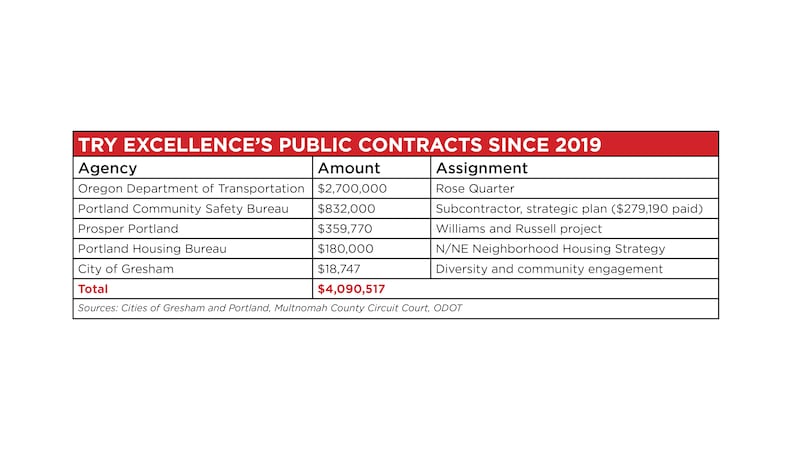

The agency paid dearly. Holt’s company, Try Excellence LLC, which includes Holt, another consultant and his son, has charged ODOT $2.7 million since 2020. (A recent contract with another government agency shows the firm charges $650 an hour.)

Try Excellence’s billings are a fraction of the more than $127 million the agency has spent on the Rose Quarter project so far, but also a measure of how hard ODOT is promoting the project.

Now, a legal dispute has placed Holt’s role as ODOT’s frontman in Albina in a new light. He filed a lawsuit, now pending in front of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, that highlights his generous compensation and the puzzling role he occupies in Portland’s Black community.

The lawsuit reveals the tensions over the Rose Quarter and how eager ODOT is to complete one of the largest public works projects in Oregon history, even as the agency is so broke it is threatening to lay off 1,000 employees. What could seem an unrelated dispute carries state- and regionwide significance. The Rose Quarter project will lie at the heart of the 2025 legislative session, the biggest-ticket item in a transportation funding package likely to include sweeping tax increases.

Over the past four years, ODOT has bet big on Holt to secure the support of the Black community, crucial to the centerpiece of the transportation funding package. Is it working?

Not in the eyes of Urban League of Portland CEO Nkenge Harmon Johnson, who has been sued by Holt for defamation.

“I’d call him a vulture, but vultures serve a purpose in nature,” Harmon Johnson says. “I believe Steven Holt only serves himself.”

In some ways, Dr. Steven Holt wasn’t the most obvious choice to promote ODOT’s project to Portland’s Black community. For one thing, although he grew up in Portland, records show Holt has lived in Vancouver for the past 20 years.

“He talks a lot about rebuilding Black Portland,” says Maurice Rahming, president of O’Neill Construction Group, one of the city’s leading Black-owned contracting firms, “but he doesn’t live here.”

Holt acknowledges that’s true, but says, as a young husband and father of three, he couldn’t afford to buy a home in Portland, and says his address is irrelevant. “I work in the city of Portland. I grew up in the city of Portland. Many of my family members live in Portland,” he says. “I went to church in Portland, and many of my closest relationships are in Portland.”

Before he became a consultant, Holt’s Linkedin page shows, he held a variety of jobs: frozen food manager at a Safeway, Christian school teacher, financial adviser, and pastor. Records show he lost his church, the International Fellowship Family on Northeast 122nd Avenue, to foreclosure in 2012.

“Some of the greatest leaders in our history have been foreclosed on, filed for bankruptcy, and or lost one thing or another,” he says.

Holt founded his consulting firm, Try Excellence LLC, in 2015. He picked up his doctorate from United Graduate College and Seminary International, an online Bible school, the following year. (He now leads a virtual flock called the Kingdom Nation Church.)

Try Excellence serves many clients. Since 2019, records show, the cities of Gresham and Portland, Prosper Portland and ODOT have collectively signed contracts with Holt’s company worth more than $4 million (see chart, page 16). He has served as the chair of the Portland Housing Bureau’s North/Northeast Housing program, which is designed to bring people who were pushed out of Albina by construction projects or gentrification back to the neighborhood.

But by far the largest paycheck came from ODOT. For that agency, Try Excellence facilitated meetings of two panels. By 2023, the two groups were whittled down to one: the Historic Albina Advisory Board, selected by ODOT consultants.

That panel’s mission is to “elevate voices in the Black community to ensure that project outcomes reflect community interests and values and that historic Albina directly benefits from the investments of this project.” (ODOT spokeswoman Rose Gerber says committee members have been paid $48,000 in cash and gift cards for their time since 2021.)

Holt says the $2.7 million ODOT has paid his company must be viewed in the proper context. He asserts that he and his staff work nearly full time on the project. “Over the past four years, three members of Try Excellence have averaged 25 hours of focused engagement on this project per week,” Holt says.

Over the years, even as the project and the makeup of the panel overseeing ODOT’s plans have changed, Holt has consistently focused on the economic benefits the department offered the Black community.

“We have an opportunity to capture the wind,” he told the HAAB at a Jan. 12, 2021, meeting, “and direct it in ways that benefit future generations.”

For more than a decade, ODOT has sought to widen I-5 along a 1.8-mile stretch through the Rose Quarter, where it narrows from three to two lanes. Data shows it’s the biggest traffic bottleneck in Oregon and the 28th-worst in the country.

In 2017, ODOT persuaded lawmakers to pay for widening the freeway. The Rose Quarter project, then budgeted at $450 million, was the largest expense in a statewide, $5.3 billion transportation package—and the only one singled out for its own cut of a gas tax increase passed that year.

Seven years later, even as ODOT has completed or made substantial progress on most other projects in the package, the Rose Quarter remains untouched.

Frederick says the status quo is unacceptable.

“There was a promise in 2017 to increase the gas tax to fix the Rose Quarter,” he says. “I believe we need to do it. We need to change entrance ramps and the exit ramps. I drive that area all the time—it’s incredibly dangerous. And if you stand there and count the trucks going through, it’s pretty damn amazing.”

Meanwhile, the project’s estimated cost has ballooned to $1.9 billion.

There are a few reasons the project stalled and the price soared. One: opposition from environmentalists led by the group No More Freeways. They argue ODOT’s plan would double the current width and carrying capacity of I-5. Meanwhile, motor vehicles are Oregon’s largest source of carbon emissions, and the state has pledged to reduce emissions at least 45% below 1990 levels by 2035.

What’s more, critics say, numerous highway expansions across the country have shown that adding freeway capacity reduces congestion only temporarily.

Another big reason the project stalled: Some Black leaders demanded that their community benefit from ODOT’s spending; and, separately, the nonprofit Albina Vision Trust demanded that the department build a cap to cover the freeway.

In 2020, ODOT signed a contract with Raimore Construction, a Black-owned Portland firm, as a step toward addressing the first concern.

Then, in 2022, Gov. Kate Brown secured $120 million from lawmakers to move Harriet Tubman Middle School from its current location at 2231 N Flint Ave., adjacent to I-5. Four years earlier, Portland Public Schools had invested more than $15 million for a super-powered HVAC system to clear the air at the school—but it wasn’t enough to quell community concerns about I-5′s emissions.

ODOT initially resisted Albina Vision Trust’s highway cap idea, saying it was too expensive. But local political leaders at the city, county and Metro, whose cooperation ODOT needed, sided with the trust.

In late 2021, Gov. Brown brokered a compromise that added a cap. That satisfied Albina Vision and local leaders but dug the project in an even deeper financial hole.

Then, earlier this year, the trust won a $450 million grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Reconnecting Communities and Neighborhoods program, by far the largest grant awarded by the feds as they try to repair historical harms done by freeway construction across the U.S.

The grant is noteworthy in a couple of ways: First, ODOT opposed capping the freeway until Brown jumped in. Second, the federal grant represents most of the money currently available for the Rose Quarter project.

In other words, there’s money for a cap, but next to nothing to expand the highway underneath. The current plan calls for a 7.1-acre freeway cover—effectively a land bridge—of which 4 acres could be developed. (Albina Vision Trust executive director Winta Yohannes says her organization is “agnostic” on whether I-5 should be widened.)

Amid these changes, Holt’s task has been to keep the Black leaders on HAAB on board with the concept of widening the highway until ODOT can persuade the Legislature to pay for it.

Throughout the past four years, Holt and Try Excellence facilitated meetings of Black leaders, massaging egos and spreading oil on troubled waters. Some board members, including James Posey, a longtime construction contractor who now heads the Portland branch of the NAACP, regularly raised concerns about whether ODOT could be trusted.

As the project grew and came to include a freeway cap, Try Excellence kept the committee focused on restorative justice and the economic benefits for Albina. ODOT would deliver contracts, real estate development, job training and other forms of reparation, Holt emphasized.

“People have been fragmented, displaced, disenfranchised, pushed into hard situations,” he told the panel on March 12. “The government comes, an agency [ODOT] comes, to fix the problem and try to resolve the issues, and they can’t do it by themselves.”

Posey says history makes it hard for him to trust ODOT. “We’ve seen this movie before,” he tells WW. “They want to build this project on the backs of Black folks without us getting any of the economic benefits.”

Nonetheless, Posey is at peace with Holt and the big paycheck Try Excellence is collecting.

“Holt is a good guy,” Posey says. “He is a good facilitator. I’m not mad at Steven that he’s making a business out of it.”

But Faye Burch, a consultant who, along with her sister, former state Sen. Avel Gordly (D-Portland), grew up in Albina, says ODOT’s reliance on Holt is typical of its failure to understand many of the people it serves.

“ODOT has never invested in the community,” Burch says, “and left it broke down, bleeding and polluted. Right now, they are just investing in a handful of community members’ personal advancement.”

Court filings in Holt’s defamation suit against Harmon Johnson of the Urban League (see “Justice League”) showed he was highly paid, but until WW filed a public records request with ODOT to find out just how much, Harmon Johnson had no idea the agency had paid Holt’s company $2.7 million to convince the Black community to go along with the agency’s plan.

“I can think of all kinds of ways nearly $3 million could improve the Rose Quarter project that don’t include Steven Holt. It’s sad ODOT could not,” Harmon Johnson says. “He lives in Washington, not here. I don’t see his footprint in our community outside of when he’s paid to be here.”

Related: Dr. Steven Holt’s lawsuit against a civil rights organization backfired.

Gerber, the ODOT spokeswoman, says the agency hired Holt’s company through a competitive process. “Try Excellence possesses specific experience and skills to help facilitate conversations and build relationships with key stakeholders, local and state leaders, as well as the broad community,” Gerber says.

Most of the criticism of the Rose Quarter expansion—and the public comment at HAAB meetings—comes from environmentalists and neighborhood groups. Most of their members are white.

At one point, Joe Cortright, an economist and member of No More Freeways, accused ODOT of “woke-washing” the Rose Quarter project. HAAB members didn’t appreciate that.

“I called ODOT ‘woke-washing grifters,’ Cortright says. He stands by that description, adding that the highway department is “repeating the same things that devastated this neighborhood in past decades.” ODOT disagrees.

At a March meeting, Holt let critics know that he’d heard enough. In an extended metaphor, Holt likened the Black residents of Albina to Humpty Dumpty—who had a great fall and needed to be put back together again—and thanked ODOT for coming to Humpty’s rescue.

“There are people who are looking on, there are people who are watching the moment and have opinions about it, and they’re weighing in,” Holt said. “I would say to those who are weighing in that, if you aren’t Humpty, your voice really should be the voice of somebody who’s listening.”

In other words, critics unharmed by the fracturing of Albina should shut up.

Earlier this summer, ODOT and the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Transportation embarked on a 12-city, statewide roadshow that will conclude in late September.

Agency director Kris Strickler’s message: ODOT is broke and might have to lay off 1,000 workers, about one-fifth of its staff.

That’s despite a gas tax and vehicle registration fee increase after the 2017 session. ODOT spent the money lawmakers earmarked for the Rose Quarter on an expansion of the Abernethy Bridge on Interstate 205 in West Linn instead. That sleight of hand irritates both the HAAB and Jana Jarvis, CEO of the Oregon Trucking Association, which lobbied hard for the Rose Quarter project.

“We devoted a penny of the [2017] gas tax increase to the Rose Quarter project,” Jarvis says. “It was the only project in Portland that was funded. Then ODOT took that funding away and spent it to benefit the trucks that are mostly bypassing the Portland region.”

Strickler says ODOT’s challenges are aging infrastructure and soaring costs coupled with tax revenues that rise more slowly than inflation. “In the absence of action,” Strickler says in his roadshow presentation, “service will be severely reduced.”

Yet, ODOT has been able to spend nearly $130 million on planning, design, engineering and public outreach for the Rose Quarter project—without turning a shovelful of dirt.

“I had no idea they’d spent that much,” Jarvis says. “I don’t know where it’s gone.”

Money troubles concern the HAAB also. Some members expressed frustration that Gov. Tina Kotek has seemed more concerned with placating suburban Clackamas County voters than funding the Rose Quarter.

In May, Holt urged dissident board members to “be careful to not just share what’s in your heart and on your mind.”

“The effort is to ensure it’s as community-informed as possible,” Holt said of ODOT’s process. “We are planting trees in whose shade we will never live.”

He tells WW he’s pleased with progress so far. “We have successfully moved the project forward and secured federal funding,” he says. The Rose Quarter project “offers the opportunity to create jobs, careers, small businesses, etc., for the people who have been most impacted by the historic harm. Try Excellence is at the center of that.”

Some lawmakers—and Kotek—know there’s an alternative to spending $1.9 billion ODOT doesn’t have in the Rose Quarter: Tolling would raise money and reduce traffic.

But in March, bowing to political pressure, Kotek told ODOT to halt seven years of work on getting motorists to pay tolls. (New York Gov. Kathy Hochul took a similar step in June.)

State Rep. Khanh Pham (D-Portland), a Joint Transportation Committee member, says Oregonians want the agency to focus its resources on safe routes to school, fixing potholes and failing bridges, and maintaining existing roads, not billion-dollar projects. “We have dire needs across the state,” she says.

Pham acknowledges the Rose Quarter is a serious bottleneck. But, she says, rather than pursue a 20th century solution—more lanes—ODOT needs to “right-size” the project.

The 21st century solution, she says, is to rebuild Albina by capping the highway and also reducing traffic through congestion pricing and tolling, tools used in many states: “That,” Pham says, “is the smart path forward.”

Kotek is watching the Rose Quarter carefully. “The governor believes centering the voices of the Historic Albina community that was displaced by I-5 construction is essential,” spokeswoman Elisabeth Shepard says. And, she adds, tolling is not off the table forever.

“The governor’s decision to pause the development of Oregon’s tolling program was made to allow for the right investment at the right time—after a robust, legislative conversation.”

Correction: This story originally said Try Excellence LLC received $832,000 from a city contract. That contract amount is correct but Try Excellence actually received $279,190. WW regrets the error.