For years, real estate broker Greg Frick has been offering what he thinks are screaming deals on apartment buildings to the city of Portland and metro-area counties for use as low-income housing. They’ve never bit, preferring to build instead.

“We’ve shown them so many properties,” says Frick, co-founder of HFO Real Estate. “It’s not as sexy as doing a new building.”

Multnomah County buys only hotels and motels, to use as shelters. Home Forward develops almost all of its own housing. Metro, the regional government, which issues housing bonds to be used in three counties, has preferred new construction, too. But chief operating officer Marissa Madrigal recommended in July that Metro consider using some of the millions it collects though the supportive housing services tax to make purchases, too.

The city has beat them both to market. Late last month, the Portland Housing Bureau put out a “Rapid Acquisition Request for Proposal,” making $15 million available to affordable housing developers to buy existing buildings instead of building new ones. The cash is coming from the city’s $211 million share of Metro’s 2018 housing bond.

The Housing Bureau’s rationale is the same as Frick’s: There are bargains out there.

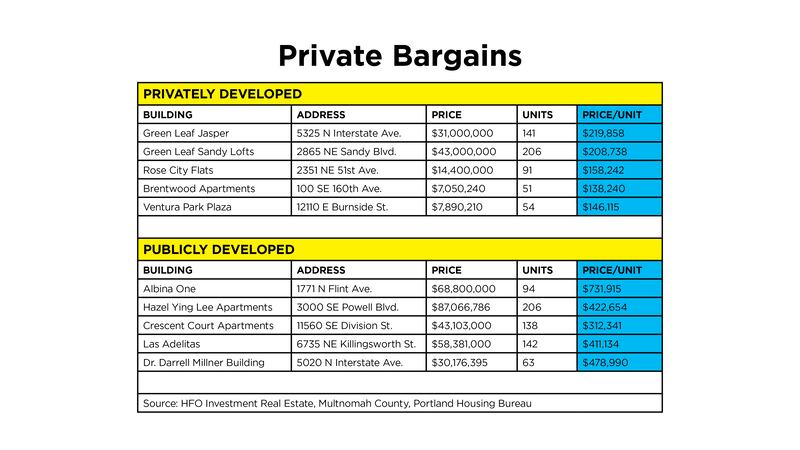

A sample of private sales shows that government housing agencies could buy apartment buildings for far less than it would cost to build comparable new ones (see chart below).

Frick says the 141-unit Perch building on North Interstate Avenue, for one, was offered to public buyers before being sold by JLL Capital Markets to California-based Green Leaf Capital Partners for $31 million, according to property records, or $219,858 a unit. By comparison, it cost a total of $58,381,000, or $411,134 per unit, to build Las Adelitas, a 142-unit complex on Northeast Killingsworth Street, almost twice as much. The Housing Bureau put in $15 million.

Why are existing apartment buildings such a bargain? Many started going up when rents were high and interest rates were low. Developers tend to borrow as much as they can in order to get the best return on their own capital.

Unlike the buyers of single-family homes, developers usually borrow for 10 years, at most. That means many loans made before the pandemic are coming due. Borrowers must either refinance or sell the asset. Because Portland rents are static or falling, a building’s rent roll may not cover a new loan with a higher interest rate. That’s when buildings get cheap.

Now, for the first time since it bought the Ellington Apartments for $47 million in 2017, the Portland Housing Bureau wants a piece of that action.

“This is a unique moment in the market,” Housing Bureau director Helmi Hisserich tells WW. “We’re putting money on the street. We expect to see some acquisitions happen.”

One fan of the new plan: former Multnomah County Chair Deborah Kafoury. In her last budget, written in 2022, she set aside $15 million for apartment building purchases. Frick had shown her good deals, and she worried that people in the buildings would be displaced if they were sold to a new private owner.

“I think it’s a great idea,” Kafoury said of the Housing Bureau’s plans. “It’s going to take every single one of these measures to get ahead of the housing crisis.”

The Portland Housing Bureau wouldn’t own the buildings outright. Rather, it would offer developers up to $100,000 per unit toward the purchase of existing buildings. At that level, the bureau’s cash would subsidize the purchase of 150 units. To be eligible targets, buildings must have at least 40 units. Sellers must be able to close between Jan. 1 and June 30, 2025. In a departure from past practice, the Housing Bureau is considering proposals on a rolling basis, evaluating them as soon as three come in, or once it has proposals totaling twice the amount of funding available, or $30 million, whichever comes first.

“It’s exciting to see [the bureau] trying to take advantage of current market conditions,” says Ed McNamara, a retired developer of affordable housing who ran REACH Community Development and later advised Mayor Charlie Hales. “As a strategy for affordable housing, this RFP could be a good way to get affordable units for less public subsidy. The possible downside is that reducing the stock of market-rate housing can put upward pressure on rents.”

The idea here is speed. Buying bargain-priced real estate requires it. Private buyers can move quickly when a distressed property hits the market, creating intense competition. Aiming to close between Jan. 1, and June 30, 2025, instead of sooner, might be too slow, housing experts say.

The Housing Bureau might be late to the fire sale, too. The apartment market probably hit maximum pain late last year, says Frick at HFO. The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond, a benchmark for commercial lending, hit almost 5% in October. It has since fallen to 3.7% as the economy cooled and inflation, which drives up interest rates, has eased. Lower rates ease the pressure on property owners in need of new financing, making it less imperative that they sell.

“Although I wish it had happened sooner, I’m glad the city has launched this RFP, and I hope they find some struggling market-rate buildings to make permanently affordable,” says Eli Spevak, owner of Orange Splot LLC, a developer of green housing. “And if a great deal requires moving faster than this RFP’s timeline, I hope the city can expedite, because the window of opportunity is closing rapidly.”

There are other wrinkles that come with turning plain old market-rate housing into affordable apartments. At least 60 days before closing, buyers using Housing Bureau funds must “educate” existing tenants on the change because, over time, owners must ease out tenants who make more than 60% of the area median income, the RFP says. And buildings must have at least some vacant units that can be offered to lower-income tenants “as soon as possible after closing.”

To entice developers to buy buildings instead of just build them, the Housing Bureau is offering so-called developer fees to purchasers, just as it does to developers of buildings. The fee is a percentage of development costs, paid to a developer right away or over time.

Winning applicants will get $4,000 per unit plus 20% for projects with up to 75 units. The percentage goes down as the number of units goes up to account for economies of scale. The most a buyer can get is $3 million.

Either there are lots of desperate sellers out there, or buyers are attracted by the Housing Bureau’s terms. A week after the window for proposals opened, the bureau already has applicants. It wouldn’t say how many.

(Correction: An earlier version of this story said that the Perch building was sold by HFO Real Estate. It was sold by JLL Capital Markets. WW regrets the error.)