Carnation Spa on Northeast 58th Avenue near Sandy Boulevard is located in a mustard-color two-story building with windows plastered with ads and flashing red LED signs that read, “WELCOME MASSAGE OPEN.”

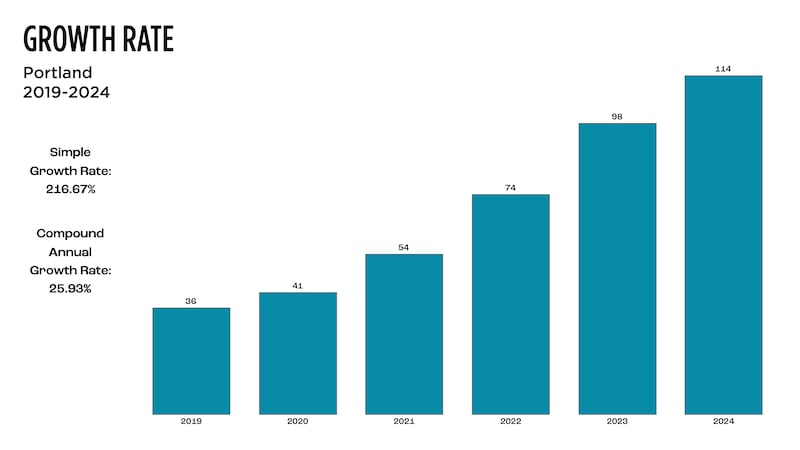

Carnation is part of a boom across Portland of massage parlors that appear on websites where men review their sex purchases. In 2019, according to data from a nonprofit that combats human trafficking, Portland had 36 of what it calls illicit massage parlors. Five years later, the watchdog says, that number has tripled to at least 114.

Those parlors, the nonprofit and state regulators claim, are criminal operations that use undocumented sex-trafficked women, often from China. Those women, state officials say, provide not only massages but sexual release, which is why such parlors are sometimes referred to as a “rub and tug” business.

Unlike strip joints, which can be magnets for rowdy behavior, drunkenness and shootings, illicit massage parlors are discreet and unobtrusive, except for their LED lights. But experts say that behind the quiet exteriors are victimized women who often have no choice in their occupation or, isolated by language and cultural barriers, the means to escape it.

“Many women in illicit massage businesses are coerced into these establishments and compelled against their will to provide commercial sex services to sex buyers upwards of anywhere from eight to 20 times a day,” says Chris Muller-Tabanera, chief strategy officer for The Network, the Virginia watchdog nonprofit that tracks the industry. “Given the nature of commercial sex, this often means they’re subjected to all forms of violence—from assault, sexual assault, rape, as well as robbery.”

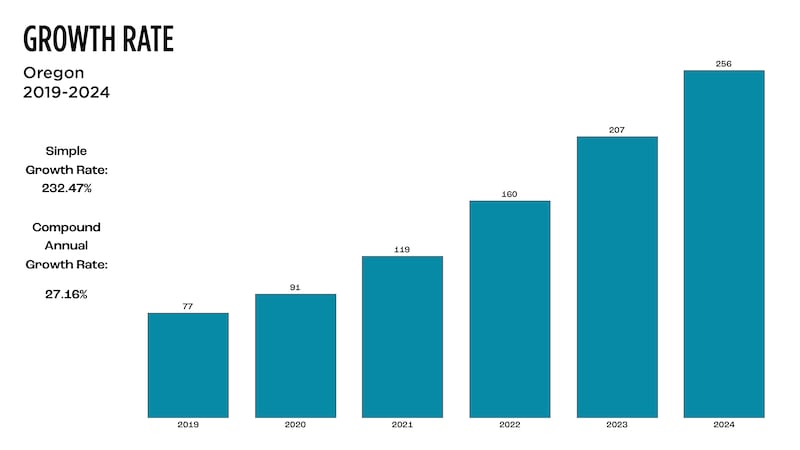

Muller-Tabanera says illicit massage businesses in Oregon have spiked at twice the national rate. “I’d suggest the regulatory environment and lack of successful enforcement across the board has created an environment that traffickers and bosses can take advantage of,” he says.

Some metro-area cities are taking action, with high-profile busts this year in Lake Oswego and Newberg.

But Portland police have not conducted such busts. And unlike other cities, Portland is not pursuing business license fixes that could deter illicit massage parlors.

Jeff Van Laanen, the compliance and licensing manager of the Oregon State Board of Massage Therapists, says his agency gets several complaints every week about illicit parlors in Portland, most of which are unlicensed.

The board lacks law enforcement authority, so all it can do is conduct investigations and send findings to the Portland Police Bureau. Van Laanen says his agency rarely gets a response.

Oregon has long taken a permissive attitude toward sex work. Strip clubs are ubiquitous, and there have been movements toward legalizing prostitution. But the regulator with the closest view into massage parlors says what’s happening in these establishments makes a mockery of those values because the workers inside are all but enslaved, right next door to residential bungalows.

“If you bring a criminal organization into your neighborhood and they’re performing prostitution, money laundering, and sex and labor trafficking right next to your convenience store and the laundromat you use, I think that should be very concerning to anybody living in that neighborhood,” Van Laanen says. “I just hate to see local law enforcement and governments not addressing this issue seriously.”

Carnation Spa is located 13 blocks from the optometry practice of state Rep. Thuy Tran (D-Portland). Tran’s district also includes Northeast 82nd Avenue, home to many massage parlors.

It troubles her. “I will continue to fight for the victims because no one deserves a life of abuse and exploitation,” she tells WW. “These inherently exploitative and illegal businesses don’t belong in our state.”

The women forced to work in massage parlors are largely invisible and hard to reach, advocates say, since they rarely leave their workplaces and often don’t speak English.

Typically when the women come to the U.S. from China, they think they’re coming for jobs—employment that isn’t sex work.

“They come here and they get processed and get holed up in these apartments in Southern California and Flushing, New York, and they’re stacked in there—four, five, six into a hotel room,” says Van Laanen. “Then they get shuttled from there to wherever they’re going to work, in whatever line of work they’re going to be doing. According to the training that I’ve been to, the top three [lines of work] are the illicit massage industry, marijuana growing and nanny work.”

“It’s hard for folks to speak up and figure out the best way to support these folks because there is no protection,” adds Marchel Marcos, the former political, policy, advocacy and civic engagement director at APANO Action Fund, a nonprofit supporting Asians and Pacific Islanders through advocacy and community development work. “If we are going to tackle this problem, which is really, really real, we need our elected officials to want to work with us and come up with a solution.”

The invisibility of the women who work in the massage parlors helps the owners earn profits and makes it difficult for advocates to help them.

“It’s very challenging for women to come forward and speak about their experiences, [and] in many ways, that trauma can blend into shame and a feeling for many women as if it’s their fault or that they did something wrong,” Muller-Tabanera says.

“What that ends up leading to is the public is unaware or uninformed about what’s actually happening, and when there are no stories of victimization, there’s no understanding that there’s a problem. And [if] there’s no problem, we don’t have to do anything about it,” he adds.

But there is an undeniable problem. The Network gathers data on suspected illicit parlors from sex-buyer review sites like Rubmaps and the Erotic Massage section of Adult Search. They then analyze and filter the data to parse out which businesses are open, marked erotic, and reviewed.

The Network estimates that nearly half of the illicit massage parlors in Oregon are operating in Portland.

And PPB’s inaction often leaves neighbors living next to the businesses frustrated and concerned about the crimes happening next door.

Martha Geisheker lives on Northeast 58th Avenue in a cozy green Craftsman separated from Carnation Spa by a sprawling hedge. A movie buff, her living room is dominated by houseplants, DVDs and stacks of paperwork. She’s lived in her home for 25 years after moving to the city for a nurse practitioner program at OHSU. Geisheker recalls that Carnation Spa began operating in August 2021.

When it opened, Carnation displayed an advertising sign of a woman holding a rolled-up towel that resembled a penis. Geisheker tore it down.

“I have two granddaughters,” she says. “It’s upsetting when they come over here and I’m thinking about them being exposed to that.”

Geisheker became more unsettled because unlike other therapeutic massage and spa businesses she’s familiar with, she found no way for Carnation’s potential customers to make an appointment online.

“The other thing I noticed was that only men were going in there,” she says.

Northeast 58th Avenue is a narrow residential street. Neighbors park their cars on the curbs, sacrificing lawns to save their side mirrors. It’s a close-knit neighborhood, and many longtime residents have noticed men parking and slinking in and out of the spa at all hours.

The phone number pasted outside shows up on websites such as adultlook.com and bedpage.com, which advertise Portland escorts. “New Asian sweet girl,” one ad reads.

Carnation’s flashing LEDs light up Geisheker’s living room, reminding her of the business even when she gets up to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night. She’s asked the spa to turn off the lights, but she says the women she tried to talk to didn’t speak English. She’s never seen them leaving the building. Her nephew says he’s seen a man bringing groceries into the spa.

“That sounds really suspect to me,” Amanda Swanson, the trafficking intervention coordinator for the Oregon Department of Justice. “That would give me enough [information] that I would definitely make a report.”

Geisheker had previously contacted the city of Portland to ask why it had allowed “a place of prostitution in a primarily residential area,” especially since there is a Catholic elementary school a few blocks away.

“I got this very perfunctory email saying it’s zoned commercial. They were very nonchalant about it even when I mentioned that I was worried about trafficking,” she says. “So the city of Portland is for shit—they don’t care.”

She’s called the police too.

“Nobody answered. I was on hold for 45 minutes,” Geisheker says. “So I went onto the website, but none of the forms they had fit for what I was trying to explain.”

The fact that she’s never seen the women leave the building coupled with their inability to speak English makes Geisheker believe they’re victims of human trafficking.

Swanson says that’s a plausible theory. “We have found that a lot of times victims will come from really rural areas of different countries in the same area their traffickers are from, so that might be the only person that speaks the dialect that they speak,” Swanson says, adding that the women often live in the businesses and the trafficker brings them food so they don’t leave the premises.

Records note the managing member of Carnation Spa is Zhiping Zeng, who in the state’s business registry lists an address in Flushing, Queens, the center of the New York borough’s Chinatown. Zeng did not respond to messages. Nor did representatives of Vuky Family LLC, the building’s landlord.

On a recent weekend evening, WW visited the spa, accompanied by an interpreter who speaks Mandarin. A woman wearing four-inch sparkly heels and a short white tennis skirt greeted us in the dimly lit front room. She agreed to talk to this reporter. WW is withholding her name.

The woman said she used to live in Flushing, N.Y., and then in Virginia. She had worked in restaurants, she said, but switched to massage parlors because the hours were more flexible, and that she moved to Portland about three years ago.

She said her compensation depended on how many customers visited, and added that there was a lot of competition with other massage parlors. But when pressed about exactly how much she was paid, the woman said it was complicated and she didn’t want to talk about it.

WW then asked if customers were ever rude, tried to make her touch their genitals or tried to touch her sexually. She became very animated, explaining that she made sure to be very professional and tell people no if they tried to do anything. She said she didn’t do those things but stayed out of other people’s business.

We asked if we could see her massage license, and she showed a picture on her phone of a license given to Zeng, the spa’s owner. (Van Laanen, the inspector, confirms Zeng is registered with the massage board, but the license applies only to him and doesn’t extend to other people working at Carnation Spa. The spa itself is not licensed.)

During a previous visit to the spa, a different woman told WW she was the only one who worked there “because business is not very good.”

But WW has seen more than five men entering and exiting the spa in the span of an hour and a half, and Geisheker says she sees men there every day. Geisheker adds that when she went over there to complain about the spa’s overflowing trash, she tried to speak to two women but they spoke no English.

Geisheker also phoned a national human trafficking hotline, but no one picked up, so she left a message.

“Seems like I should call between eight and five,” she says. “I bet they’re short-staffed.”

The proliferation of illicit massage parlors has understandably riled up neighbors. Competitors in the sex industry are also frustrated.

Stephanie, who asked WW to use a pseudonym for safety reasons, works at a lingerie shop in East Portland—not the kind of lingerie shop where you buy underwear but a business where customers can pay to masturbate while sex workers put on a show in a private room. Such businesses are commonly referred to as “jack shacks.” They are legal.

Now in her mid-40s, Stephanie says she’s been in the sex work industry since she was 18. But she says it’s become increasingly difficult to make a living.

“The last few years, the amount of rub and tugs that have popped up is just mind-bending,” she says. “I’m just like, ‘What the fuck is happening?’”

Illicit massage parlors are bad for Stephanie’s business. Stephanie explains that men at lingerie parlors can purchase a show from one of the workers for between $140 and $200. Around half of the show’s money goes to the woman working and the remainder is the house fee.

From there the price can go up depending on what the customer wants.

“So $160, that usually is like a sexy striptease type of a show, right?” Stephanie says. “And then from there, they can upgrade their show. We offer a variety of shows—couch dances, fetishes, fantasy shows, role-playing and domination shows, visual masturbation shows, and toy shows.”

Compared to an illicit massage, which Stephanie says is usually around $40 to $50 for an hour plus maybe another $40 or so for a “happy ending,” the lingerie shows are expensive.

“Why would they pay $400 or $500 for a toy show when they could just pay 80 bucks or 100 bucks for a body rub and get jacked off?” Stephanie says. “It ruins the customer. Now they’re never gonna want to pay that higher price again.”

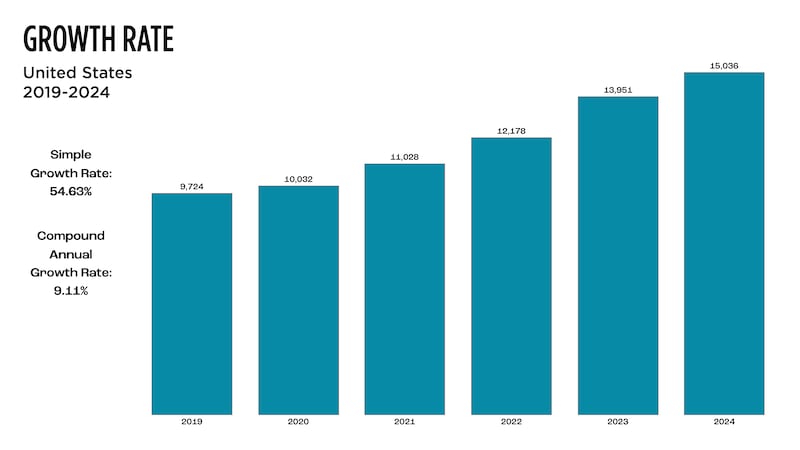

The illicit massage industry is growing all across the country. Data compiled by The Network, a Virginia-based nonprofit watchdog, shows a 9% compound annual growth rate nationwide. But that increase is much more dramatic in Oregon (27%) and Portland (25%).

The Oregon State Board of Massage Therapists is also worried about customers and the damage illicit parlors create for legitimate massage businesses. The board is in charge of renewing licensing, teaching courses, and regulating massage practices.

The board employs just six people but only one compliance specialist in addition to Van Laanen, who splits his time between licensing and compliance. The agency has been overwhelmed by the dramatic increase in illegal businesses, and while it can fine practitioners and businesses, it can’t pursue any legal action.

Van Laanen has worked for the massage board since 2019. In his free time, he helps teach a blacksmithing workshop to veterans and first responders with PTSD. But during working hours, he’s been trying to find ways within the board’s jurisdiction to combat illicit massage operations.

“We’re busting our butt on this,” Van Laanen says. “We’re about 1.5 full-time employees trying to combat this statewide. And it’s a lot with one hand tied behind your back because we don’t even have the power to close the doors.”

Van Laanen says that out of the businesses they investigate, an estimated 80% of the time the women they find working at the massage parlors also live there. “I would further estimate that about 75% of our IMB investigations involve sexual misconduct, either offers of prostitution and/or sexual assault on our investigators,” he says.

Investigators have occasionally seen women who work in illicit massage parlors covered in bruises. But “due to the fear and secrecy, law enforcement has been unable to prove they were assaulted by either the handlers or the customers or both,” Van Laanen says.

Van Laanen could not share a list of other massage parlors under investigation or recently investigated due to confidentiality requirements under state law. The Network declined to share the list of the 114 businesses it’s identified in Portland, saying that given the sensitivity of the information, they only share its data with law enforcement and government agencies.

In July 2023, Lake Oswego police started investigating Flora Spa, which they suspected to be an illicit massage parlor. Their suspicions were confirmed, and in February they conducted a sting that resulted in the arrests of two people who have been charged with crimes, including promoting prostitution.

Lake Oswego police said their investigation revealed that Flora Spa was involved with a multidistrict trafficking operation with suspects in multiple states.

The police have identified at least 10 women who worked at Flora Spa as victims of sex trafficking, and detectives have worked with advocacy groups to help get support for the women. Their investigation is ongoing.

In July, a similar bust happened in Newberg. Community members sparked the investigation, unsettled by the peculiar businesses of Amber Massage and Lavender Foot Spa. Investigators were offered sex multiple times when they went undercover to the locations and both of the massage licenses displayed in the establishments were fake, Van Laanen says.

Two people were charged with prostitution and one person was charged with promoting prostitution. That investigation is also ongoing.

“I think there’s a misconception, especially when you’re talking about prostitution, that this is a victimless crime,” says Newberg police detective Robert Mitchell. “The reality is when you have these illicit massage businesses, you have people who are potentially being trafficked. These are people who are there potentially involuntarily and are forced to work in this environment to make money. There’s nothing mutual about it.”

One measure some cities are taking is passing ordinances that require extra inspections for applications for a massage business license. An ordinance allows cities to have more control of the business licensing process. It might require the owner to appear in person at City Hall, submit to an interview, and, on occasion, submit to a background check or provide proof that everyone working there is properly licensed.

“Once you start to make those requirements, these criminal businesses don’t want to go there anymore because they don’t want that exposure,” Van Laanen says.

Scappoose was the first Oregon city to pass such an ordinance, aided by Van Laanen. After Lake Oswego and Newberg busted establishments in their cities, those cities contacted the massage board for help creating an ordinance.

Van Laanen says he hasn’t heard from the city of Portland.

While other cities have been cracking down on illicit massage parlors, PPB has not. The bureau declined interview requests, responding instead with a statement.

“The Portland Police Bureau’s Human Trafficking Unit is aware there are criminal groups that are connected to human trafficking which use the guise of massage parlors in the Portland area,” a PPB spokesperson wrote in an email. “Investigators are actively investigating these locations and cases and therefore we cannot share details as we do not want to jeopardize the investigation.”

(Over the past three years, PPB has tripled the budget for its drugs and vice unit from $3.3 million to just over $10 million.)

Mayor Ted Wheeler, who has overseen the police bureau for nearly eight years, deferred to PPB’s statement.

When WW told Geisheker that the police declined to tell WW what the bureau is doing about places like Carnation, she expressed dismay. “It’s repugnant,” she says. “I always thought of Portland as a cool town where we were trying to look after each other, and this certainly isn’t that.”

Her brows bunch up as she thinks of the women next door, just 50 or so feet from where she sits on her living room couch.

“They’ve been there for three years, and they don’t even get out to get outside and get fresh air or go for a walk or have any kind of life outside of being told what to do,” she says. “It’s heartbreaking that the police don’t want to do anything about this.”

Eliza Aronson reported this story during an internship with the Charles Snowden Program for Excellence in Journalism at the University of Oregon.