We trust you know by now that the Multnomah County ballot you’ll get in the mail next week will look like nothing you’ve ever seen before.

First, Portland voters must choose 12 City Council members (up from four, the number since 1913). Second, we will choose them through ranked choice voting. Third, we have to get comfortable with the ideas that three candidates will win a seat in each of four districts and that more than 25% of the vote is enough to secure one of the three seats in, say, District 1 (East Portland).

New things are scary. Three new things all at once can be terrifying. That’s why we answered readers’ questions one by one this summer, attempting to explain how RCV works, both in the mayor’s race and in multimember districts.

But maybe you spent the summer at your beach house in Gearhart or you had oral surgery and got into a little trouble with the painkillers. We don’t know your life. This is a judgment-free space where we provide the answers to questions readers submitted about RCV, which you might still have.

Do we vote for council members for all districts or only ours?

Only yours! Your ballot will be tailored to your address, so you won’t even see candidates for other districts. But don’t let that get you down. With RCV, you can choose up to six candidates in your district. Multnomah County’s HAL 9000-level computers will tally all the votes (see below) and spit out three winners.

How many candidates can I vote for?

You may choose up to six (like ordering a half dozen doughnuts at Sesame), ranking them in order of preference.

How do I indicate whom I like best?

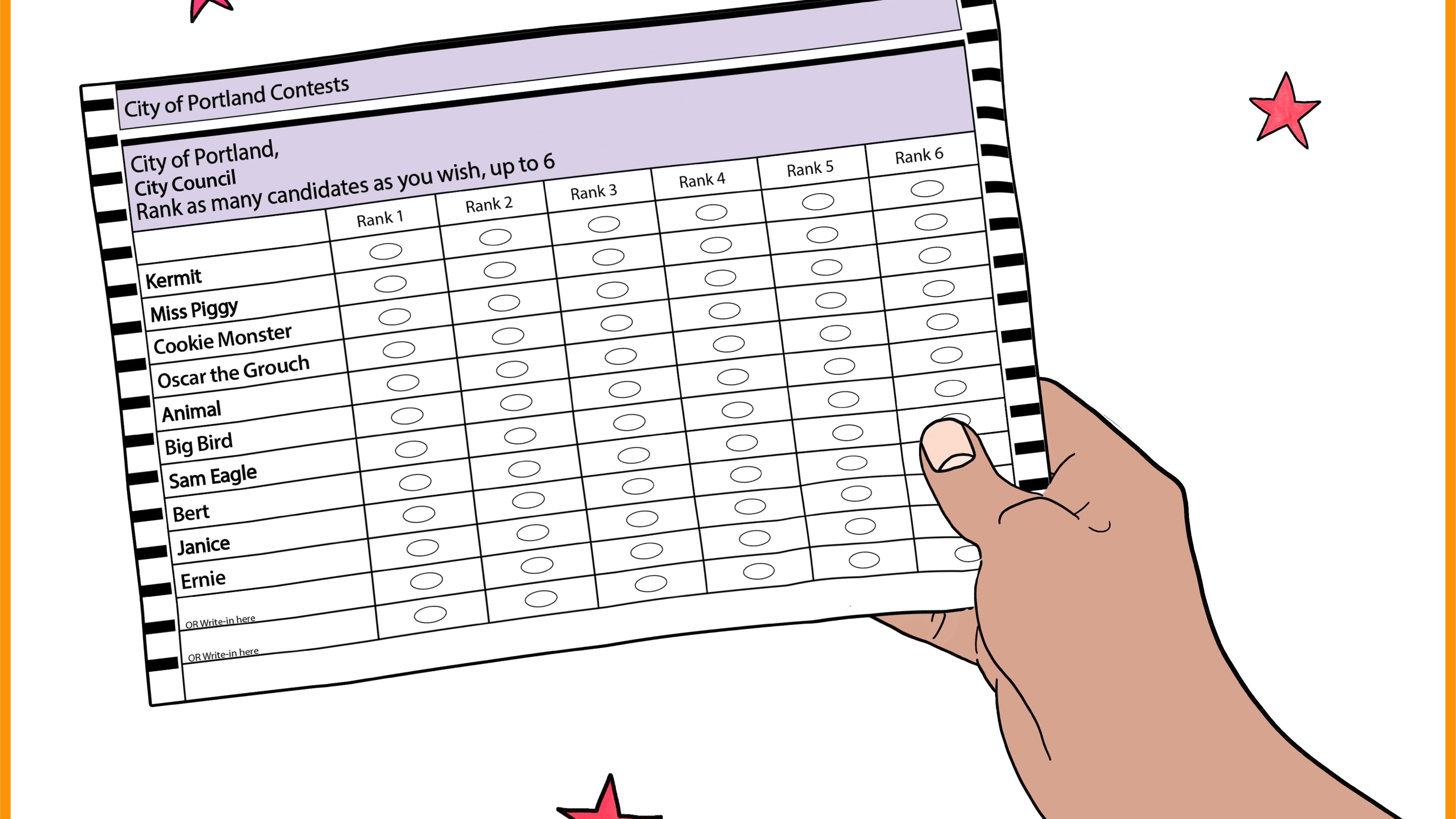

Take a look at the mock ballot below. Looks like a damn spreadsheet, right? You’ll see a list of candidates down the left side of a grid and preferences across the top (Rank 1, Rank 2, Rank 3…). We’ve used the Muppets as an example. If you love Miss Piggy and believe she is the best choice to represent you in elected office, you would fill in the bubble marked “Rank 1″ on the line by her name. If you really, really like (but don’t love) Fozzie Bear, you might fill in the “Rank 2″ bubble by his name. And so on. (Wocka! Wocka!)

Can I just choose one candidate in a race?

Absolutely. But you’d be robbing yourself of the extra democracy RCV promises. You could bet it all on Miss Piggy, fill in only one oval, and turn on Netflix. If Piggy loses, your ballot is out and you forfeit your chance to express any preference for another candidate. But if you mark Fozzie as your second choice, your vote will go to him, and the bear just might win. Or your third choice might. Or your fourth. As they say in the lottery, you can’t win if you don’t play, and the more numbers you pick the better your chances.

Let’s say of all the candidates, there are fewer than six I can even stomach. If I’d rather be represented by a mop with googly eyes than Rene Gonzalez, am I better off leaving it blank?

The best strategy for haters is fairly simple: You have the option to rank up to six candidates, but it’s perfectly fine to rank fewer if you support only a couple of them. In districts with multiple representatives, votes trickle down from top-place finishers to lower ones once the top dogs reach 25% plus 1. Each of our four new districts will have three city councilors, so it’s not winner-take-all. Big winners, in fact, have to share!

Placing Candidate X at the bottom of your list ensures your vote won’t inadvertently support them unless all other choices are eliminated. And they could be! So it’s best to not support the candidate you loathe at any level. (Indeed, after we answered this question in July, people who despise Rene Gonzalez launched an independent expenditure called “Don’t Rank Rene,” though this was probably a coincidence.)

How are the votes counted?

It’s pretty simple for races that have one winner, like mayor and city auditor. If your top candidate is the least popular and no other candidate has 50% plus 1 vote, your second choice gets counted. If no one gets to 50% plus 1 after the second round of tabulation, the process repeats until someone goes over the top.

But wait, there’s more! Each of the four new City Council districts will elect three councilors, and because of the math, each one needs just 25% plus 1 vote to win. That bugs critics who question whether one-quarter of the vote is a true mandate. And these “multimember districts” make it harder to distribute second, third, fourth, fifth and sixth ranked votes if necessary.

Say after Round 1, Miss Piggy has 25% plus 1. Miss Piggy cracks the bubbly and kicks back to watch the next round. But if she gets, say, 40% of the vote, she doesn’t need the extra 15% to win. That excess is instead distributed to the second choice on those ballots.

But there’s a wrinkle: You have to make each of the second-place votes worth a fraction because you’re counting them all, and that includes votes that went to the winner. If you gave those winning votes full credit, then a voter who ranked Miss Piggy first would get two votes. The fraction functions to remove the winning votes. RCV aims to give each voter greater chances of having their vote count, but only one vote can count.

The crazy thing is all these calculations must be done in every round until we have three winners in each of the four districts. Computers make that possible.

How long will all this take to count?

Regardless of the complexity of ranked choice voting, the count won’t take longer than normal, says Multnomah County spokesman Denis Theriault. Preliminary results will include round-by-round tabulations received to that point, Theriault says, and tabulations will be run from scratch for each preliminary update.

In the dreaded event of a ranked choice recount, triggered if a result is within two-tenths of a percentage point, the county will rely on “a small army of humans, plus lots of large tables and color-coded folders, to accomplish an analog version of what the tabulation software can produce in seconds,” Theriault said in an email. “It’s just counting, cross-checking and basic math, and time. There’s no mystery here.”

This article is part of Willamette Week’s Ballot Buddy, our special 2024 election coverage. Read more Ballot Buddy here.

This article is part of Willamette Week’s Ballot Buddy, our special 2024 election coverage. Read more Ballot Buddy here.