Fast Stats

- Population: 159,498

- Percentage of residents registered to vote: 66%

- Largest population of color: Latino (14.8%)

- Median household income: $61,000

- Percentage of population with a bachelor’s degree: 25%

- Nathan Vasquez’s vote share in May: 57%

Sources: City of Portland; John Horvick, DHM Research

East Portland Wants Diversity and Cops

East Portlanders are outliers in many respects. In a survey by the Oregon Values and Beliefs Center this past spring, the district’s residents described being left behind. They’re dissatisfied with a host of public services and are the most likely to say Portland is on the wrong track.

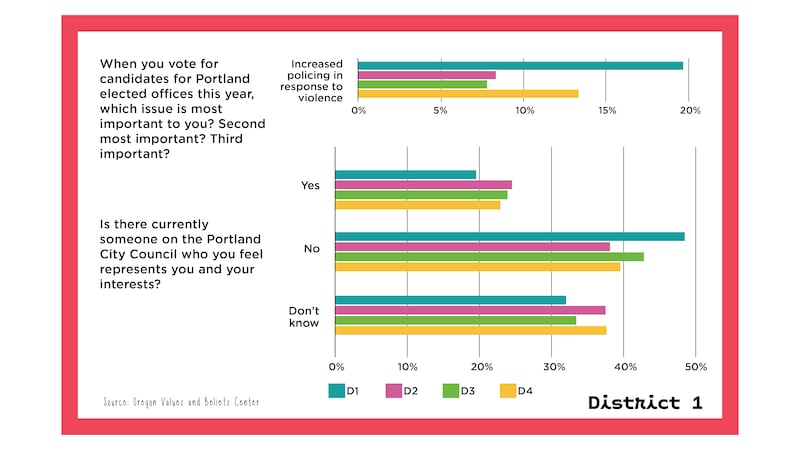

But two data points stick out and are hard to reconcile at first glance. East Portlanders overwhelmingly say increased policing in response to violence is a top priority. About 19.7% of them ranked this as their most important issue when determining who gets their vote. At the same time, they’re also more likely to feel that no one on City Council represents them or their interests, at 48.4%. Given that the district is Portland’s most racially diverse, liberals might conclude those two data points are at odds. But OVBC executive director Amaury Vogel says wanting increased policing and more representation don’t have to be mutually exclusive. “Communities of color and particularly small business owners are more likely to experience all kinds of crime,” she says. “Unfortunately, in Portland, more policing generally means less representation. It doesn’t have to be that way.” —Joanna Hou

Gateway Breakfast House

11411 NE Halsey St.

Sixteen candidates are vying to represent East Portland on the Portland City Council in this November’s election. But no one in the Sunday brunch crowd at the Gateway Breakfast House seems to be able to name any of them.

To be fair, they have more pressing concerns.

Nash Caron, 34, is in nursing school, doing his coursework between shifts as a nursing assistant at a local hospital. Politicians have generally let him down, he says. Rhetoric doesn’t match reality. When Caron pulls out his voters’ pamphlet come November, he’ll be looking for someone new. “I do feel like a fresh face would be better,” he says.

Nate Hoang, a 39-year-old construction worker, is over it. The last politician he trusted was Bernie Sanders. “I don’t think I’m going to vote,” he says. “Not this election.”

The conversation soon turns to everyone’s commutes. No one here is working from home.

Driving, everyone agrees, is getting harder. “We need to hand out reflector tape to homeless camps,” says diner manager Judy King, 59, who’s somehow juggling the phone, bar orders and the register without missing a beat. “They’re all wearing black—you can’t see them. I almost hit them all the time.”

Instead, the Portland Bureau of Transportation is implementing traffic calming measures. The neighborhood has new roundabouts. (“No one knows how to use them,” King says.) There are also dividers down the middle of 122nd Avenue.

“It’s ridiculous. You can’t turn left. Now you detour past a grade school,” King says. “Are they high?”

Who’s she favoring for City Council? One of her regular customers is a candidate, although she doesn’t reveal who. “I haven’t decided yet,” she says.

It’s not just King who thinks city leaders have lost the plot. This summer, when WW spoke to voters in this easternmost district, they described a bone-deep dissatisfaction with nearly every service provided by City Hall (“What East Portland Wants,” July 17). The sense that Portland has abandoned these neighborhoods is reflected in the district’s survey responses—and in this restaurant.

Sunny Burton, 21, has been coming to the Breakfast House at least “since Barack showed up” in 2012. (There’s a plaque honoring the table where former President Obama sat.) Burton didn’t meet him but he remembers hearing the helicopter fly over.

Burton is a graduate of David Douglas High School and now an electrician in training. He’s helping to build the houses every politician says need to be built. So why, he wonders, is getting permits such a pain? Permits for new houses run north of $10,000.

“It doesn’t seem like it should cost so much,” he says. Inspectors don’t even bring their own ladders, he adds.

For others, the frustration has curdled into something more unruly. Nick Zarandi, 34, a housepainter who frequents the diner despite living outside the district, is sitting at the end of the counter, wearing sneakers and a black T-shirt with a picture of Kim Jong Un throwing up a Bloods gang sign. Zarandi moved to Portland from Idaho because the pay was better. Then prices went through the roof. “I miss gas being $1.35,” he says.

Talk turns to voter fraud, which Zarandi believes is rampant. “I found out I can vote twice,” he claims.

King, somehow still listening, cuts in. “You plan on breaking the law?” she says. “Don’t mess up the election. Don’t do it just because you can.” LUCAS MANFIELD.

This article is part of Willamette Week’s Ballot Buddy, our special 2024 election coverage. Read more Ballot Buddy here.

This article is part of Willamette Week’s Ballot Buddy, our special 2024 election coverage. Read more Ballot Buddy here.