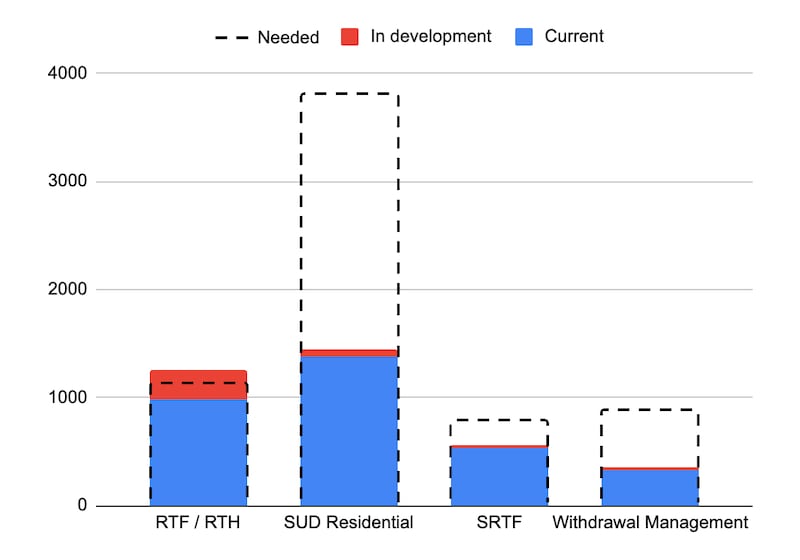

A WW review of new data shows the state of Oregon is building more residential mental health treatment beds than its own consultants say it needs while struggling to construct other types of treatment.

These facilities house people with mental illness in small unlocked buildings with between five and 16 residents. A state-funded study released early this year says the state needs 1,131 of these kinds of beds.

The new data, which was briefly published on the Oregon Health Authority’s website last week before being taken down, shows the state is on track to surpass that number. It already has nearly 1,000 of these beds and is in the process of building around 250 more.

Meanwhile, the state is nowhere close to meeting its goals in other categories of behavioral health treatment. For example, the same study notes the state currently has around 300 beds in detox facilities and needs three times that. According to the new data, the state has 26 detox beds “in development.”

Same for more “secure” versions of mental health treatment beds, which could take some pressure off the perpetually overburdened state psychiatric hospital, which houses criminal defendants. The state says it needs hundreds more, but only 32 are “in development.”

It took OHA a week to respond to WW’s questions about the new numbers. Shortly before publication of this story, the agency confirmed that construction was outpacing the state’s calculated need but explained that overbuilding has advantages.

“Many of these investments were directed by the Legislature before completion of the statewide residential treatment bed study Gov. Kotek directed OHA to conduct,” says OHA spokesperson Timothy Heider. “The total new RTF and RTH beds exceed the study’s estimate of need by approximately 10%, which gives the state appropriate flexibility in the event providers have unexpected difficulties given the complexity of establishing these types of programs.”

The governor’s office denied to WW that the state had overbuilt, echoing this explanation.

To be sure, the state needs more mental health treatment facilities of all types. WW reported on Oct. 7 that a Marion County judge was demanding the state hospitalize a man accused of serial public masturbation, at the cost of $40,000 a month, because there was no bed available at a smaller, cheaper residential treatment facility.

And the state’s slow progress at spinning up other types of treatment facilities is understandable. Lawmakers only began funding them in earnest in 2021, and building specialized facilities for higher-acuity patients takes time. It’s far easier to create new residential treatment homes, which can operate out of residential houses.

On the other hand, the fact that Oregon is in the process of building more lower-acuity beds than it needs raises questions about state oversight of the hundreds of millions of dollars lawmakers are showering on Oregon’s broken behavioral health care system. That concern has been raised repeatedly by opponents of new funding mechanisms, like a tax on alcohol, that could help fix it.

The office of Gov. Tina Kotek, who originally demanded the study shortly after taking office last year, tells WW she’s glad to have additional information to set policy.

“The state now has more information than ever before to meet the need with precision, and we are taking action,” Kotek says.