A new report from the nonprofit Up for Growth found that the nationwide housing shortage eased slightly in the last year for which there is data—but even within that slightly positive change lie the seeds of an even bigger looming shortage.

Up for Growth defines housing underproduction as the difference between the housing a state has and the housing it needs. Nationwide, underproduction stands at 3.89 million units in 2022, down 50,000 units from 2021. That’s the first decline the group has calculated since it began running the numbers in 2012. (One of its key contributors is Mike Wilkerson, a housing economist at the Portland consulting firm ECONorthwest.)

For Oregon, the underproduction number declined by nearly 10,000 units in 2022, leaving the state short 78,000 units and placing us among the 10 states with the largest housing deficits.

“On its surface, the leveling of housing underproduction seems like positive news,” said Up for Growth CEO Mike Kingsella. “Instead, it illuminates the negative effects of long-term housing shortages along the West Coast. What’s happening in San Francisco should serve as a cautionary tale for metros like Nashville and Houston, which are struggling to adequately meet rising demand.”

What is happening in San Francisco—and in Portland, to a lesser extent—is that the housing shortage is temporarily improving, not because of the construction of new housing but because people are moving away to cheaper places.

In a case study on San Francisco, the Up for Growth report noted an issue that a report from the Common Sense Institute Oregon highlighted earlier this week.

“Household formation in these areas significantly decreased. Driven in no small part by the high cost of housing, households that could have formed in these communities formed somewhere else instead,” the Up for Growth report says. “This phenomenon, as observed in the San Francisco Bay area, could explain why the middle of the country shows worsening underproduction while the West shows overall improvement.”

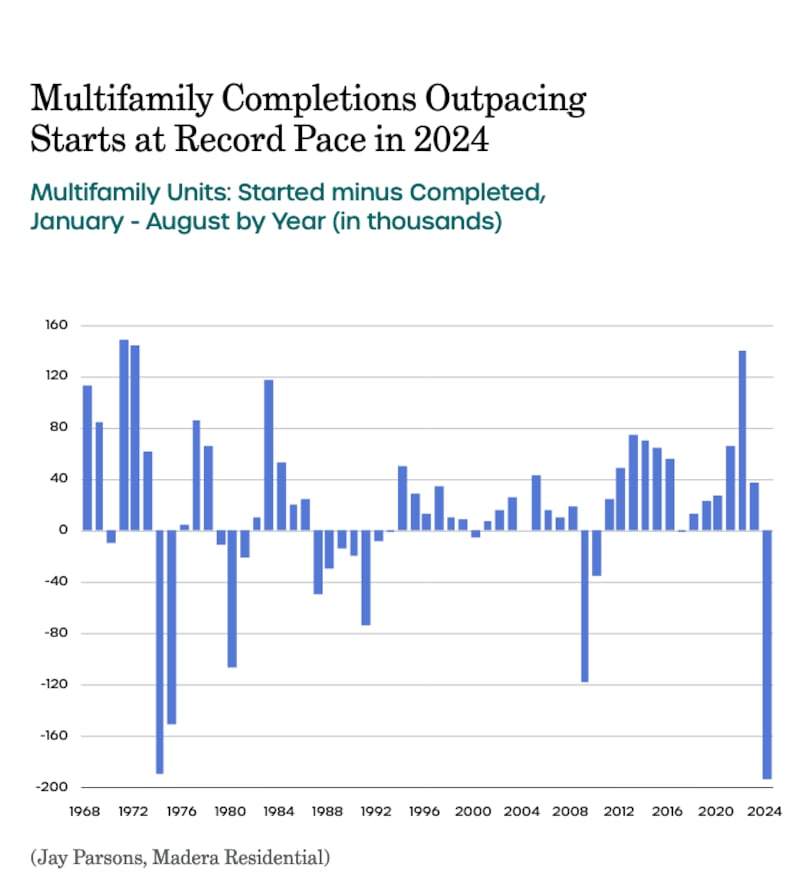

One graphic, that shows the difference between the number of apartment units completed and the number started in the first half of 2024 tells the story of why the group is pessimistic: The pipeline is empty nationally, as it is in Portland.

“Peak delivery of multifamily homes occurred in 2024, about 2 years after the peak of permit cycle,” the report says. Beginning in 2025 and continuing for at least one year, multifamily unit delivery is expected to steeply decline.”

That’s the case in Portland, as well.

In August, ECONorthwest’s Wilkerson released a study projecting Portland would issue the lowest number of new housing permits this year since 2009. In a follow-up interview, Wilkerson told The Oregonian that local conditions are dire: “There continues to be no institutional-scale development.”