Update, Wednesday, Nov. 6: Following the election results, Commissioners Rene Gonzalez, Mingus Mapps and Dan Ryan abandoned their plan to withdraw from the contract.

Three Portland city commissioners announced last month their intention to sever the city’s contract with Multnomah County to fund the Joint Office of Homeless Services.

The two entities have pooled their resources to address homelessness since 2015 (thus the word “joint” in the office’s name). The abrupt demand for a divorce by Commissioners Rene Gonzalez, Mingus Mapps and Dan Ryan was quickly decried by County Chair Jessica Vega Pederson as an election-season stunt—Gonzalez and Mapps are running for mayor; Ryan is running for City Council.

But their maneuver leaves a lot of unanswered questions about what exactly would happen if the city ended its contract with the county and the two walked their separate ways in their responses to homelessness.

Here are five questions the contemplated split raises.

1. What led up to this?

After a year of tense negotiations, the Portland City Council and the Multnomah County Board of Commissioners approved a three-year contract in June governing the Joint Office of Homeless Services. The city signed the agreement on several conditions, including that the county give the city more oversight of the Joint Office and its budget.

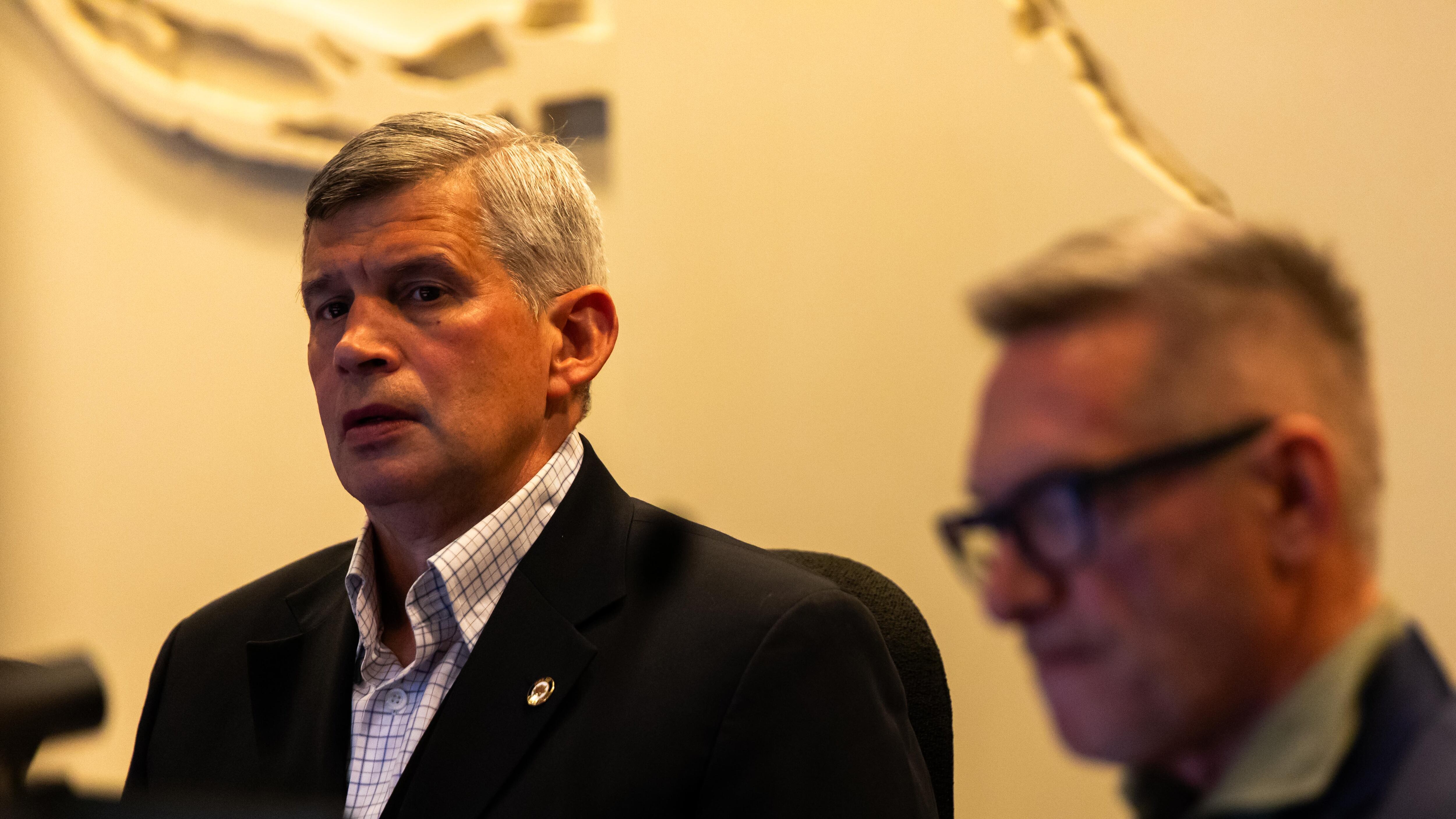

But Commissioners Gonzalez, Mapps and Ryan weren’t pleased with the Joint Office’s performance. In a straw poll on the dais Oct. 16, planned that morning by the commissioners’ respective offices, Gonzalez asked his two colleagues whether they would vote to leave the contract in the coming weeks. (Mayor Ted Wheeler was absent.)

Mapps, Ryan and Gonzalez agreed—they would all vote to end the contract before they left office at the end of the year.

The first reading of the termination ordinance is scheduled for Thursday. The final vote is set for Nov. 13. Mayor Wheeler and City Commissioner Carmen Rubio are expected to vote against the ordinance.

2. What’s the root of the dissatisfaction?

The three commissioners say the county has failed to live up to the pledges it made in the most current contract. They say the city should take back the money it gives to the office and use it more efficiently.

But the city contributes comparatively little money—$32 million a year—to the Joint Office’s $343 million annual budget. Vega Pederson says their motive is more cynical: They want an election-year boost at her expense. “This abrupt withdrawal from a brand-new partnership throws the work unnecessarily into chaos,” she wrote Oct. 28 to Felisa Hagins, executive director of the SEIU Oregon State Council.

It’s true that Vega Pederson’s approval ratings are dismal, and city leaders on the ballot this week stood to gain some cred with voters by disavowing the county’s spending strategy. But it’s also notable that the move to sever ties was praised by County Commissioner Sharon Meieran, an always reliable critic of the chair.

“In my view, and I hope yours, the best thing the city could do is to withdraw from the city-county agreement,” Meieran wrote in an Oct. 28 email to the three city leaders.

3. When would the severance take effect?

June 30, 2025. The current City Council that voted to sever the agreement will be no more, and the new 12-member City Council taking office in January will have just started to get its sea legs.

4. Could the new council reverse the decision?

Yes, but only by a majority vote. Whether the future City Council decides to restore the contract is difficult to predict without knowing who will be elected.

5. If the deal is severed and there’s no new contract in place, what would be the city’s shelter responsibilities and how would it pay for them?

If this City Council terminates the agreement and the next City Council opts not to negotiate a new contract, the city would continue to operate its safe rest villages, which contain sleeping pods, and TASS, its two temporary alternative shelter sites. Annual expenses to operate the shelters and provide services is $40 million—more than the $32 million the city currently contributes to the Joint Office.

That would leave the city with an $8 million operating budget deficit. The current Joint Office contract schedules the county to take over operation of TASS and the safe rest villages from the city on July 1, 2025. If the contract is severed, the city would be left to fund and operate its shelters without county assistance.

Gonzalez, Mapps and Ryan say they would seek money directly from the Metro regional government’s supportive housing services tax to help fund the city’s current shelters and future shelter beds.

Multnomah County currently receives about $150 million annually from the tax that flows into the Joint Office. Cities, however, cannot receive direct allocations from Metro, per the ballot measure that established the tax. The city could only receive SHS dollars if the county elected to hand them over.