A new examination of the assumptions underlying the proposed Interstate Bridge between Portland and Vancouver says the project relies on bogus numbers.

The new study was commissioned by the Just Crossing Alliance, which wants to reduce the freeway component of the project but supports parts of it, including the seismic replacement, light rail extension and bike and pedestrian improvements.

“The traffic modeling the whole IBR environmental impact statement is based on is a work of fiction,” says Chris Smith of the Portland group No More Freeways, which is part of the Just Crossing Alliance.

Norman Marshall, president of Smart Mobility Inc., a Vermont traffic consulting firm, says the rationale for building a new, wider bridge (estimated cost: $5 billion to $7.5 billion)—that it will relieve congestion—is simply wrong.

“The congestion is caused by bottlenecks to the south—at North Lombard in the southbound a.m. peak and at Victory Boulevard in the p.m. northbound peak,” Marshall wrote in his report. “And there is no possibility that widening the bridge can address those problems.”

Greg Johnson, program administrator for the bridge replacement, which is a joint venture between the Oregon and Washington transportation departments, says Marshall’s criticism misses the mark.

“The Interstate Bridge replacement program is a 5-mile segment in a regional transportation network,” Johnson says. “While IBR investments will reduce congestion and improve safety at the I-5 Interstate Bridge, we cannot solve the region’s congestion problems, such as bottlenecks outside of the program area, but we can do our part to make it more efficient. Design improvements, multimodal investments, including extension of light rail and express bus enhancements, safety shoulders throughout the IBR Program area, variable rate tolling, and the addition of an auxiliary lane across the bridge to enhance ramp-to-ramp connections will help improve the flow of traffic both on the bridge and throughout the IBR 5-mile program corridor.”

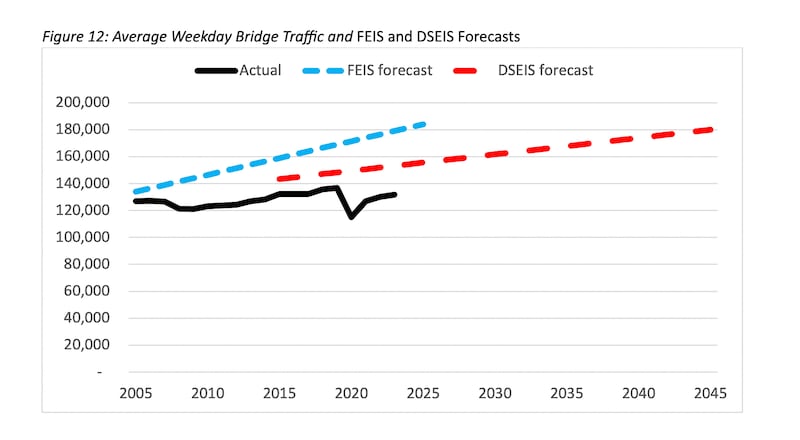

Marshall’s report says the draft supplemental environmental impact statement, a federally required document meant to take a comprehensive look at the costs and benefits of the project, relied on old numbers and an outdated forecasting model. He provided a couple of examples of how the methodology underlying the project has previously produced inaccurate forecasts of traffic volumes.

Here’s a snapshot of how previous projections have overestimated daily traffic on the I-5 bridge.

And although truck traffic moves essential goods across the bridge and is hampered by congestion, Oregon Department of Transportation data included in Marshall’s report shows truck traffic is down over the past 20 years. City Observatory first reported the truck data.

Marshall writes that nobody should be surprised that the traffic projections are inaccurate. He says they rely on an outdated “static” model rather than a “dynamic” model, and that the resulting traffic estimates are “preposterous.”

“The model used to predict future traffic cannot even accurately predict current traffic levels,” Marshall writes.

The IBR program’s Johnson acknowledges the draft supplemental environmental report relies on old numbers and a static model from the regional government Metro, but he says his colleagues have augmented that model with additional analysis.

“Traffic modeling presented in the draft supplemental environmental impact statement is based on the most current information available when IBR started modeling work to support the draft SEIS: the 2018 Regional Transportation Plan jointly developed and adopted by both Metro and the Southwest Washington Regional Transportation Council,” Johnson says.

“The IBR program conducted analysis and modeling in addition to the Metro regional travel demand model to produce future traffic forecasts in the program area,” Johnson adds. “The data and methods used to create regional travel demand model traffic forecasts and the additional traffic operations models completed by the IBR program that are included in the draft SEIS used industry best practices for predicting future travel and to plan for regional infrastructure needs.”

Metro spokesman Nick Christensen defends his agency’s work, adding that it believes a bridge replacement is necessary.

“The model results we provided to IBR are from a model that looks at travel patterns at a regional level—it estimates the number of daily trips across the Columbia River on both bridges. The ‘dynamic’ model Mr. Marshall cites is a supplement to, not a component of, regional models like Metro’s. IBR did not ask Metro for any data beyond the output from the regional ‘static’ model we provided,” Christensen says.

“We think our model performs well when estimating transportation choices at a regional level—the basis for a lot of decisions on large projects, like the proposal to replace our 107-year-old drawbridge over the Columbia River.”

So what’s the solution? Marshall says the highway departments should focus on using cheaper tools, such as ramp meters or tolls, to manage traffic more efficiently. (Gov. Tina Kotek earlier this year ordered ODOT to halt the Regional Mobility Project, which was aimed at using tolls to reduce traffic on Interstates 5 and 205, but tolling the I-5 bridge remains a live option.)

“The ramp meter system can be improved, but it likely will be impractical to rely solely on ramp metering,” Marshall’s report says. “Variable tolling certainly can achieve uninterrupted flow on I-5,” the report concludes. “The sum of the monetary value of the resulting time savings would be far greater than the out-of-pocket toll expenses, and equity issues could be addressed through investments in non-auto travel modes and with targeted rebates.”

The IPR program is taking public comment on the draft supplemental environmental impact statement through Nov. 18. To make a comment, click here.