The timing was uncanny. On Nov. 14, friends of the late Bob Sallinger’s showed up at a Metro Council meeting to support an ordinance honoring “the life and legacy” of the conservation leader who died by suicide Oct. 30.

Mike Houck, director of the Urban Greenspaces Institute and an ally of Sallinger’s for decades, led off the tributes with a request.

“If you truly treasure Bob’s legacy, I ask that you move expeditiously to bring West Hayden Island into Metro’s system of parks, trails and natural areas,” Houck told the council. “No one has done more than Bob to make that possible. Protection of West Hayden Island is one of Bob’s singular achievements. The most appropriate and meaningful way to honor Bob’s legacy would be to protect it in perpetuity.”

Houck adds that since the name West Hayden Island bears no apparent significance, Metro might consider renaming it after Sallinger. “Why the hell not?”

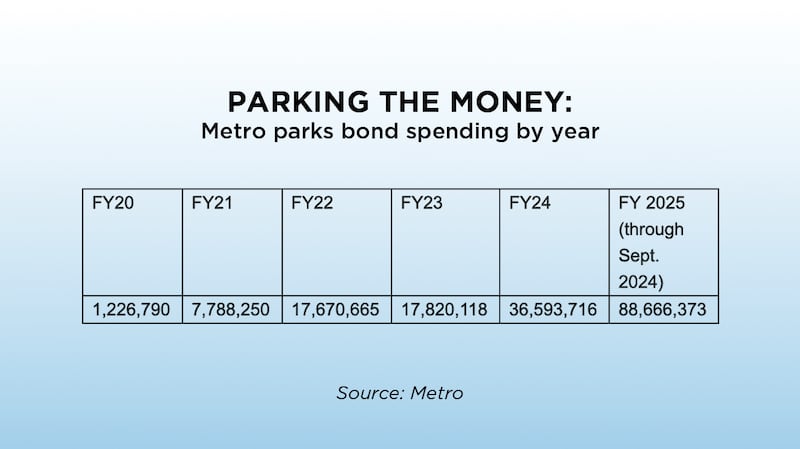

The regional government certainly has the money to make the purchase. Immediately following an outpouring of tributes for Sallinger, Metro presented the annual report for the $475 million parks bond voters approved in 2019.

A key data point: Five years after voters approved the measure, Metro has spent less than 19% of the money raised. The spending so far is shown in the chart below.

That raises three immediate questions.

WHY IS METRO SPENDING SO SLOWLY?

Metro spokesman Cory Eldridge says the agency can’t just throw cash at projects. “We said from the beginning that it would take time to complete the bond’s foundational work,” Eldridge says. “The first years of the bond were spent getting new programs stood up, aligning established programs to new criteria, dealing with the challenges of the pandemic, and planning, designing, permitting and implementing construction projects.” That also means the spending has been heavy on administration so far—17% of the $88.7 million has gone to admin, a percentage Eldridge says will decrease to under 10% as projects kick in.

WHAT IS WEST HAYDEN ISLAND?

Back in the 1980s, the Bird Alliance of Oregon (whose efforts were led by Houck and Sallinger) started agitating to protect the 685-acre North Portland greenspace just east of the confluence of the Columbia and Willamette Rivers. Environmentalists defeated plans, first by Portland General Electric and, later, the Port of Portland, to develop the island for industrial use. Houck, an architect of Metro’s first greenspaces bond in 1995, says the whole idea of asking the public for money is to protect and restore property that would otherwise be developed. He’d like to see Metro do so quickly and efficiently. “The whole point,” Houck says, “is to get land into the system as cheaply as you can.”

WHAT DOES THE PORT SAY?

In 2014, the port, which bought West Hayden Island from PGE in 1994, reluctantly abandoned its decadeslong plan to build a new deep-water marine terminal on the island. In 2022, port director Curtis Robinhold told the Metro Council he couldn’t see that development would ever be an option (translation: Houck and Sallinger won) and the port would be interested in “transferring ownership of West Hayden Island to Metro.” It’s now 2025, of course, and that hasn’t happened. “The port remains interested in selling,” says spokeswoman Kara Hansen. “Valuation has yet to be determined.”