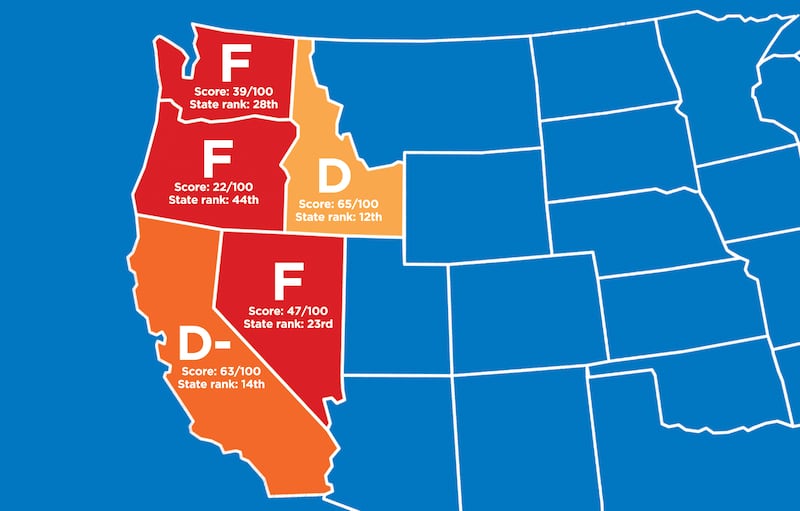

Almost every U.S. state has what are known as compassionate release laws, which give elderly and severely ill inmates a chance for early release. Oregon’s laws are some of the worst in the country, according to a 2022 scorecard released by the nonprofit Families Against Mandatory Minimums.

“They got an F,” notes FAMM general counsel Mary Price. “But that’s not unusual.”

What stood out for Price, and helped land Oregon at 44th among 50 states, was the state’s extremely vague eligibility criteria. That makes it easier for officials to deny applications. For many years, only a handful of inmates successfully completed the process.

This lack of a release valve has fiscal consequences. As WW reported last year, state officials say Oregon’s prison population is aging at an “alarming rate,” leading to skyrocketing medical costs at prisons that are not designed to operate as nursing homes.

There have been repeated efforts to reform Oregon’s laws. But four bills introduced since 2021 have all failed. And their standard-bearer, Sen. Michael Dembrow, is retiring at the end of this year.

Still, the eastside Portland Democrat remains optimistic. Why? Because the Oregon Board of Parole, which oversees the program, is taking matters into its own hands.

The board has proposed a new set of rules governing the early release process, including a standardized application form and definitions for ambiguous terms.

Some advocates, including Dembrow, say it’s a step in the right direction. “They’re recognizing that the system has to change,” he says.

But Zach Winston, policy director at the Oregon Justice Resource Center, fears that greater clarity might send the state in the wrong direction. For example, the new definition for “severe medical condition”—any impairment that “would require care in a hospice setting or residential medical facility”—could reduce the number of inmates who qualify, he says.

“We don’t think the rules move the needle,” he says. “We think they further restrict eligibility.”

Winston prefers the approach outlined in past legislative proposals and expected to be put forward again next this year, which would create a new committee of medical professionals to review applications.

Meanwhile, the board’s proposed rules face opposition on another front. The Oregon District Attorneys Association, which has historically opposed legislative reform on public safety grounds, says it too has “significant concerns” about the new rules.

Among them: the costs of reviewing hundreds of new applications from inmates seeking to take advantage of the new eligibility criteria. “I anticipate there are [adults in custody] who believe they fit within this definition—but really don’t,” Polk County DA Aaron Felton recently testified before the board.

The parole board’s executive director, Dylan Arthur, said it is anticipating more applications, which he says “may increase” the number of inmates being released early.