For decades, Portland didn’t have to worry about population declines. People flocked here for the lifestyle, the nature, the coffee, the beer.

That calculus changed in 2020, when Multnomah County lost population for the first time since 1987, before Portland could sustain itself with jobs at Nike and Intel. The exodus led to a debate over why people were leaving. Business groups and real estate experts said taxes levied on high earners to pay for universal preschool and homeless services were to blame. The Oregon Center for Public Policy, a left-leaning think tank, said that was bunk (“They Left,” WW, Feb 1, 2023).

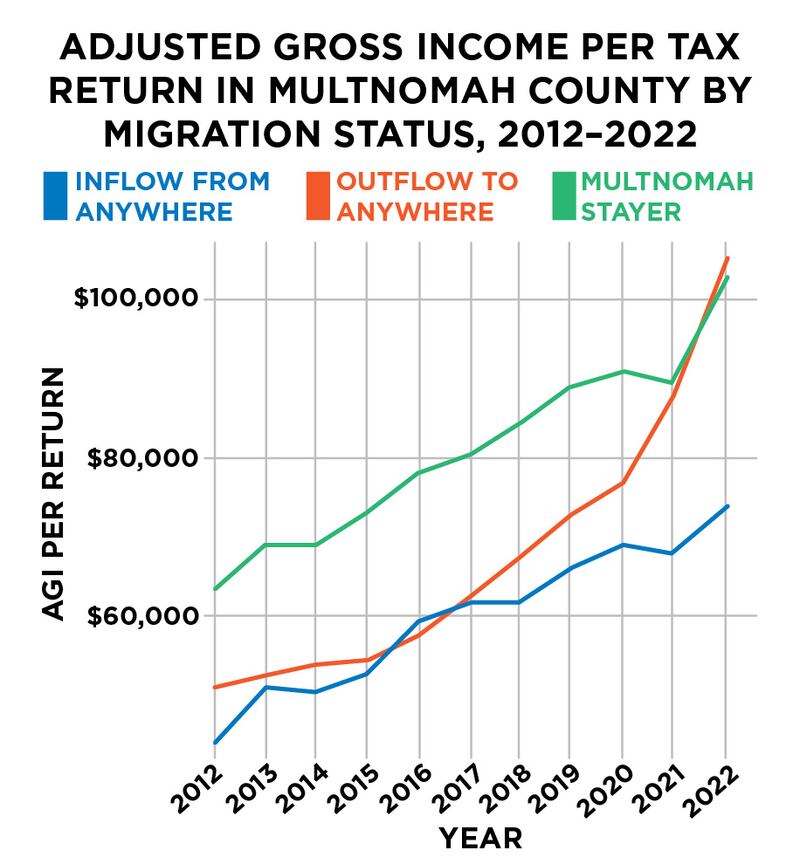

Another authority weighed in on the matter last week. The tax advisory group of the Portland Central City Task Force, a panel convened by Gov. Tina Kotek in 2023 to rehabilitate Portland in the wake of the pandemic, said damn right, taxes were chasing the wealthy away. It produced the chart below to prove its point, referencing the sharp incline in the red line starting in 2020, when the Preschool for All tax and Metro’s supportive homeless services levy passed. It shows the average income of people skipping town is now slightly higher than that of people sticking around—and more than $20,000 a year higher than the average income of new arrivals.

In addition to using data, the tax group reached back into economic history to justify its claim. It cited a “highly influential” paper written by economist Charles Tiebout in 1956 that said households sized up taxes and services when deciding where to settle. If things got rough, they would be more likely to move than to try and change things by voting. This assertion became the basis for the “Tiebout Model.” Citizens would choose their communities according to the level of taxes they were willing to pay and services they wanted to receive.

Tiebout, a professor at the University of Washington, died suddenly in 1968 at the age of 43, so we can’t ask him what he thinks about Portland migration. He made some assumptions that make his theory, well, a theory. He assumed people could move at no cost and that they would have perfect information about tax rates and services in a variety of places.

Do you know the top marginal tax rate in Vancouver, Wash.? How about the frequency of trash pickup? The acreage of parks there? Would you ever look up such things when considering a move? The tax panel of Kotek’s task force seems to think you might.