For years, Multnomah County took heat from voters and from Metro, the regional government, for not spending its allocation from Metro’s supportive housing services tax, a veritable geyser of money that voters approved in 2020.

These days, Multnomah County is pushing money out the door. In a recent presentation, county officials offered a slide showing that they had spent $96 million of SHS dollars in the first four months of the fiscal year that began July 1, triple what they spent in the same period last year.

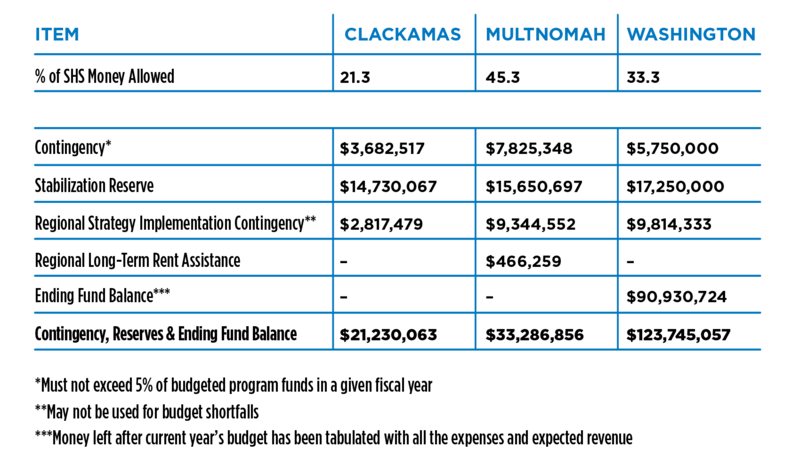

Now, depending on whose numbers you believe, suburban Washington County might be the laggard. Metro says the county has a $91 million “ending fund balance,” defined as money that’s left over after the current year’s budget has been tabulated with all the expenses and expected revenue. Combine that with two contingency funds and a stabilization reserve, and Washington County has $124 million in budgeted contingencies, reserves and fund balances, according the the most recent figures the county has provided to Metro.

Washington County says that number is dead wrong in part because the latest forecast for SHS tax receipts, released in December, shows the program bringing in $323 million, down from the $375 million forecast in November 2023.

Nor does the $91 million ending balance include commitments Washington County has made recently, including construction funding that lasts beyond this fiscal year, says county spokeswoman Emily Roots. Neither Multnomah County nor Clackamas quibble with Metro’s numbers.

The figures matter because the SHS program is in flux. After years of raising far more cash than expected, receipts are coming back to earth. And Metro is pushing for changes to the tax that would extend it by 20 years to 2050 but possibly lower the 1% rate levied on all marginal income above $125,000 for single people and $200,000 for married couples.

So far, the counties have been leery of Metro’s push to put the changes before voters this year. All of them applauded Metro’s recent decision to shoot for the November ballot instead of May.

Washington County Chair Kathryn Harrington has been among the most vocal opponents of change. Once a Metro councilor, Harrington has taken a tough stand against her old shop.

“Washington County has focused on building a comprehensive program supporting the resources, workforce and infrastructure that can meet people where they are and transition folks into permanent, stable housing,” Harrington said in a statement to WW. “We want to show that we have transitioned from building the system to that of operating and improving the system. We are now afraid that we will be sliding backward if reform proposals reduce funding or reallocate funding without local review and input.”

Given the softer forecast for SHS receipts, Harrington says Washington County could have to cut back on services that are working so well there. Her county, she says, has moved almost 1,200 people into housing and removed “virtually every major encampment.”

But what if she had an extra $90 million? That’s Metro’s point. Even with the forecast getting weaker for this fiscal year and the next, the SHS tax is still on track to bring in north of $300 million annually for four consecutive fiscal years, compared with the $250 million projected when voters passed it.

Extra money would also cushion the blow from any decrease in the SHS tax rate that comes with extending the program for another 20 years.

In short, Metro says Washington County is crying wolf, and Washington County is saying that Metro can’t do math (Metro says it used the figures that Washington County provided and did no math). The disagreement adds tension to a relationship already strained by three years of trying to get a data-sharing agreement among the counties and Metro, another thing that looks doable from the outside. The latest roadblock there: The counties want a certain number of days to review any of their data before Metro shares it

(Updating to show that Washington County has $124 million in budgeted contingencies, reserves and fund balances. An earlier version of the story used the colloquial term “in the bank.”)