Lawmakers love to right wrongs, create new programs, and battle injustice. But sometimes, they just get stuck cleaning up messes they didn’t create.

That’s what Oregon House Bill 2096 and two companion bills are about. The bills follow a 2023 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the case of Tyler v. Hennepin County. In 2015, Hennepin County, Minn., foreclosed on a condo owned by a 94-year-old woman named Geraldine Tyler because she had failed to pay $15,000 in property taxes. The county sold the condo for $40,000 and kept the $25,000 in excess value.

The Supreme Court ruled that holding on to such a windfall was an unconstitutional “taking.” Oregon law mirrored Minnesota law, so lawmakers scrambled. In 2024, they passed a bill that did little more than tell Oregon’s 36 counties, which collect property taxes, to figure out how to repay people whom they now owed—and to establish a fair process for liquidating foreclosed properties in the future.

Here’s the situation:

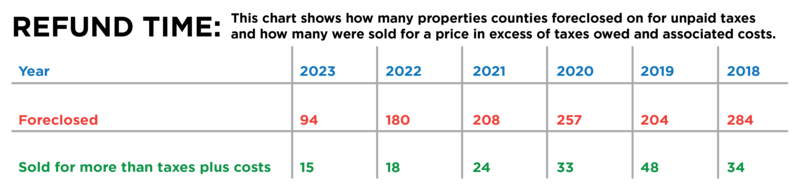

WHAT’S THE PROBLEM? Oregon counties now have to figure out how many property owners they owe money to, how much they owe the property owners, and how far they need to look back in time to find them. The Association of Oregon Counties gathered partial data last year (22 counties, including all the big ones, provided data). At least 172 properties would have qualified for a refund since 2018. One of the issues lawmakers are grappling with now is how far back they should look (somewhere between six and 10 years) and how diligent they must be in tracking down heirs. Former state Rep. Charlie Conrad (R-Dexter), who co-led an interim work group on the issue, says resolution will require an enormous effort by county assessor’s offices, many of which are ill-prepared. “You have almost no staff to handle this in the smaller counties,” Conrad says.

WHAT’S HAPPENING NOW? Advocates and lawmakers are debating how best to find elusive beneficiaries, whether foreclosed properties should be appraised, and whether they should be sold at auction or by real estate agents. Meanwhile, the private market is also hard at work. Entrepreneurs who learned of the Tyler v. Hennepin ruling are scurrying around the state acquiring the rights to claim equity repayments due on foreclosed properties. In other words, speculators are persuading owners of foreclosed properties to sell them their equity at a discount. “There are LLCs buying up judgments,” state Rep. Emerson Levy (D-Bend) says. Levy, who served on work group that prepared HB 2096, adds that such companies stand to earn 50% returns: “It’s quite usurious, in my opinion.”

WHAT’S THE SOLUTION? In Minnesota, lawmakers created a $109 million fund in 2024 to compensate property owners whose equity the state had taken. Members of the Oregon work group think the number here will be less—perhaps more like $50 million. But the state, not the counties, is likely to be on the hook because the counties were following state law when they kept all foreclosure proceeds. Levy says a pending lawsuit on behalf of property owners who are claiming more than $500,000 under Tyler v. Hennepin in Linn County could help determine the ultimate cost to the state. “Until that case is heard, we are really at a standstill,” Levy says.

This story was produced by the Oregon Journalism Project, a nonprofit newsroom covering rural Oregon. OJP seeks to inform, engage, and empower readers with investigative and watchdog reporting that makes an impact. Our stories appear in partner newspapers across the state.