At the end of 2021, a nonprofit critical to Portland’s tree-planting goals was largely axed from the city’s payroll. Friends of Trees, which had planted thousands of street trees annually for more than a decade, primarily through a contract with the Bureau of Environmental Services, got caught up in an intracity fight between BES and Urban Forestry.

Environmental Services, which oversees sewers, stormwater and bioswales, had a permit from Urban Forestry to plant trees in city rights of way. But Urban Forestry, driven by city forester Jenn Cairo, wanted to bring all street tree planting across the city under its roof.

Tensions between Cairo and BES had been festering for years, three current employees of the bureau tell WW. Over the years, Urban Forestry had made stricter rules around BES’s planting, making it more difficult to plant trees. Amid those tensions, as Oregon Public Broadcasting detailed in a June 2022 story, Cairo asked BES to hand over all of its tree-planting duties to Urban Forestry—but continue to pay for them.

After months of talks between BES and Urban Forestry management, the two agencies failed to come up with an agreement by which the bureau could continue to plant street trees under a UF permit.

Matt Glazewski, liaison at the time for BES for City Commissioner Mingus Mapps, says the ordeal imploded any remaining relationship between the two agencies. Glazewski recalls then-BES director Michael Jordan, now the city’s administrator who’s known for his unflappably calm demeanor, becoming upset when he learned his bureau and Urban Forestry had failed to agree on a new permit for BES to keep planting street trees.

“I have never seen that man so mad,” Glazewski recalls.

The upshot: Friends of Trees was pushed out, after 15 years with the city.

Three BES employees who spoke to WW on the condition of anonymity say severing ties with Friends of Trees negatively impacted the city’s tree canopy because it siphoned off a powerful resource for volunteer-led tree planting across the city by a trusted nonprofit. (Cairo denied in a recent interview with WW that she played a prominent role in consolidating the city’s tree planting, saying instead it was the decision of bureau directors. She later partly walked that back, saying she “strongly advocated for the alignment of street tree planting.”)

Another policy decision by Cairo at about that same time had similarly negative effects in portions of North, Northeast and Southeast Portland, sources say, where the tree canopy is lacking. Urban Forestry told BES in 2016 it could no longer plant trees in planting strips that were less than 3 feet wide; many of the planting strips in the neighborhoods barest of trees east of the Willamette River are 2½ feet wide. One neighborhood where the policy would’ve brought street tree planting to an almost complete halt: Woodlawn.

“Those were a lot of the open locations that needed trees,” says Kelly Koetsier, a former Urban Forestry inspector who left the program in 2019. “But for Urban Forestry, it was a hard no.”

BES director Mike Jordan appealed UF’s order, noting in his June 15, 2016, appeal letter: “It is our responsibility to identify and challenge policies that reinforce inequitable treatment and institutional racism. The planting ban is such a policy.” Jordan added that 96% of the 20,000 available planting spaces that would be affected by the rule change were in “low-canopy, low-income areas and communities of color.” Hoping to keep the disagreement out of the public appeals process, the offices of Commissioners Amanda Fritz and Nick Fish brokered a last-minute deal.

But Jordan’s appeal only managed to delay the UF order. In 2019, Cairo’s rule change went into effect, ending a longtime exception for BES’s program and reverting to what was written in the Tree Code.

UF defends its decision, saying that “smaller spaces reduce tree longevity and productivity and are more likely to damage adjacent sidewalks and other infrastructure which can increase maintenance costs for property owners.”

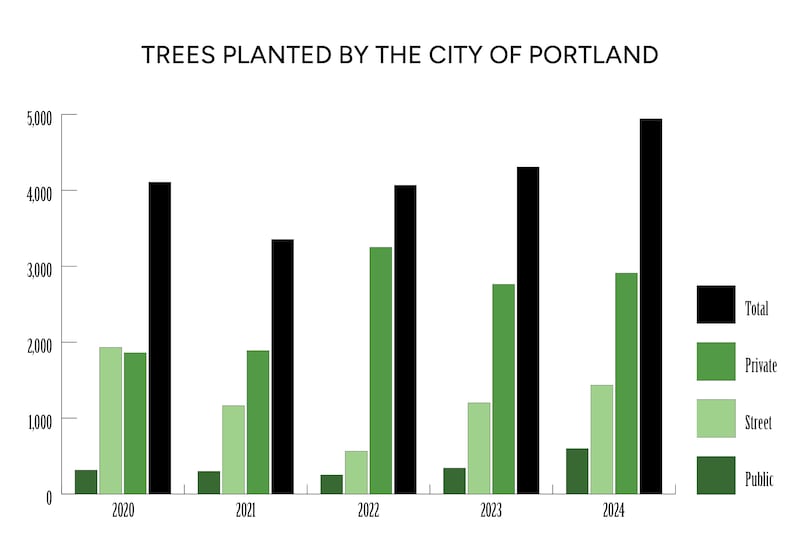

Data provided by the parks bureau appears to support BES’s assertions that street tree planting suffered in recent years. In 2020, the city planted 1,932 street trees. In 2022, that number dipped to 565 street trees. The total appears to be creeping back up: The city planted 1,434 street trees in 2024 (see graph above).

Parks spokesman Mark Ross argues, however, that the data does not represent what matters most: where trees were planted (with a stronger focus on East Portland neighborhoods) and what types of trees—bigger ones that will offer more shade.

Data also shows the city has increased the number of trees distributed for planting on private property in recent years, though critics respond that Urban Forestry didn’t actually plant most of those trees but instead simply handed the saplings to homeowners.