A Feb. 26 joint hearing in the Oregon Legislature on school funding and student outcomes saw a rare moment of bipartisanship. Reps. Emily McIntire (R-Eagle Point) and Ricki Ruiz (D-Gresham) shared a laugh when Ruiz said McIntire had stolen his question about whether the high rate at which Oregon students opt out of testing was reflected in poor student outcomes.

After asking if students were allowed to opt out of a national assessment, McIntire asked presenters: “Would you say that it’s a real accurate report of where each state stands?”

The researchers, for their part, said the data they were presenting was accurate, but the exchange raises deeper questions about how Oregon measures up to other states when so many students here skip the tests.

In 2015, then-Gov. Kate Brown signed House Bill 2655, which requires districts to send out notices to parents and allow them to opt their children out of state exams. For years since, Oregon has not hit the federally mandated 95% testing opt-in rate.

But this legislative cycle—amid a push from Gov. Tina Kotek for school funding to be paired with accountability—those opt-outs have been magnified.

Oregon’s outcomes are dismal, and education experts who spoke to WW say high opt-out rates aren’t an excuse for low achievement. But they might have other consequences.

“There’s no question Oregon’s opt-out policy poses a real challenge to building an effective and trusted K–12 improvement plan and accountability system,” says Louis Wheatley, a spokesman for education accountability nonprofit Foundations for a Better Oregon.

Here are two key points:

THE DATA’S STILL GOOD: Sarah Pope, executive director of Stand for Children Oregon, a nonprofit that advocates for public education, says she’s concerned that some legislators have used opt-out rates as excuses for poor performance in Oregon schools.

“We have a statistically significant percentage of kids taking [state standardized tests],” Pope says. “I get worried people use that as an excuse.”

Participation rates have also risen for most students between 2022 and 2024. Students in grades 3 through 5 posted participation rates of about 93.5%, with middle schoolers closer to the 90% mark. Rates only dip in 11th grade, which can influence total student averages. Oregon Department of Education spokesman Peter Rudy says participation rates at or above an 80% threshold should be sufficient to indicate student performance at schools and districts.

And even if lawmakers are test-score averse, Pope adds most indicators of education system health in Oregon trend in the same negative direction. The state is still struggling with chronic absenteeism and low on-track graduation rates.

“We have 94% of third graders and fourth graders taking these tests, and yet the literacy rates in the state are among some of the worst in the country,” says Jessica Cobian, Stand for Oregon’s policy and government affairs manager. “By facing that, we’re going to be able to get answers and get solutions.”

BUT IT’S HARDER TO PUT IT IN CONTEXT: One of the more widely anticipated education studies, the Education Recovery Scorecard, released its results Feb. 11. The research project, conducted as a joint effort between Harvard and Stanford universities, assesses how states have recovered from learning loss during the COVID-19 pandemic. It received national coverage because of its findings: Most states are still experiencing disappointingly slow recovery, especially ones that were locked down for longer.

But Oregon wasn’t part of the study this year, which compared recovery based on student testing data from 2019, 2022 and 2024. That’s because it didn’t meet the federal guidelines of 95% participation, says Sam Stockwell, a spokesman for the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard.

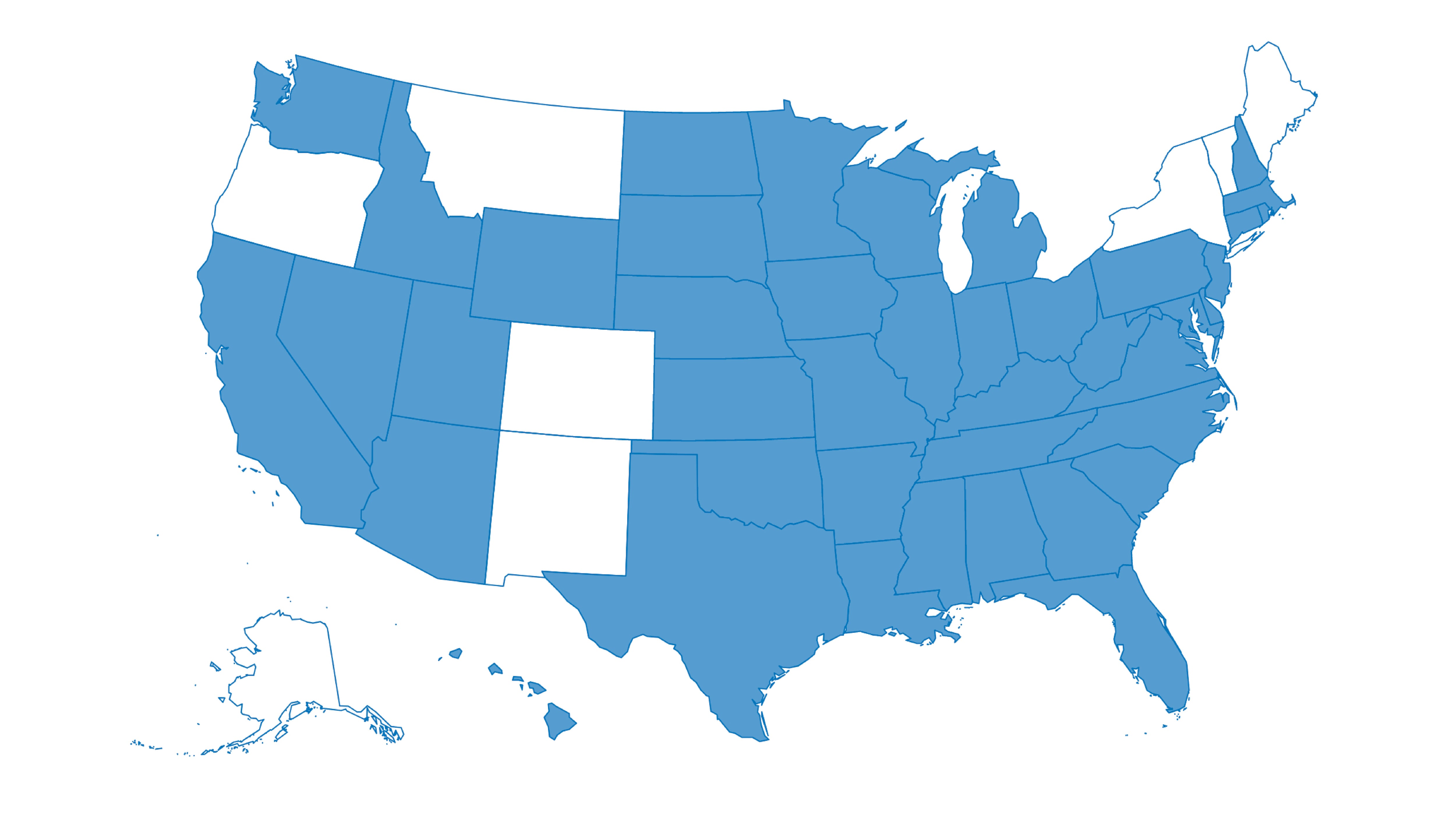

Oregon is one of just eight states that didn’t meet the threshold, including three other Western states: Colorado, New Mexico and Montana (see map above).

“Low statewide participation limits our ability to put Oregon estimates on a common scale for comparison with other states,” Stockwell says.

That’s bad news for the Oregon Department of Education, which says it’s trying to make accountability its top priority. Last year, the Recovery Scorecard made waves because it showed that Oregon was the only state out of 30 studied between 2022 and 2023 that did not improve its math achievement and was among a few states that lost additional ground in reading.

Rudy, the ODE spokesman, says the opt-out legislation “has had substantial, negative effects on student participation in Oregon’s state summative tests.” The department has met with school districts struggling to increase participation, and tried to encourage testing, he says.

“ODE is most concerned about being able to leverage our state assessment system to meet its intended purposes,” Rudy tells WW. But until the state hits the golden 95%, it will miss out on some independent analyses.

“When we just compare ourselves to ourselves, we don’t really get a good picture,” Pope says. “These national comparisons are really important.”