Given how often Gov. Tina Kotek talks about housing, and how many initiatives she’s rolled out to increase the supply, you’d think she’d raze Mahonia Hall to make way for luxury condos.

In particular, Kotek wants more market-rate houses and apartments, not just affordable ones. It’s a bet that increasing the total inventory will make more of that inventory affordable. On March 6, she and Portland Mayor Keith Wilson convened a group of builders and developers at City Hall to spitball ways to speed up construction of private complexes.

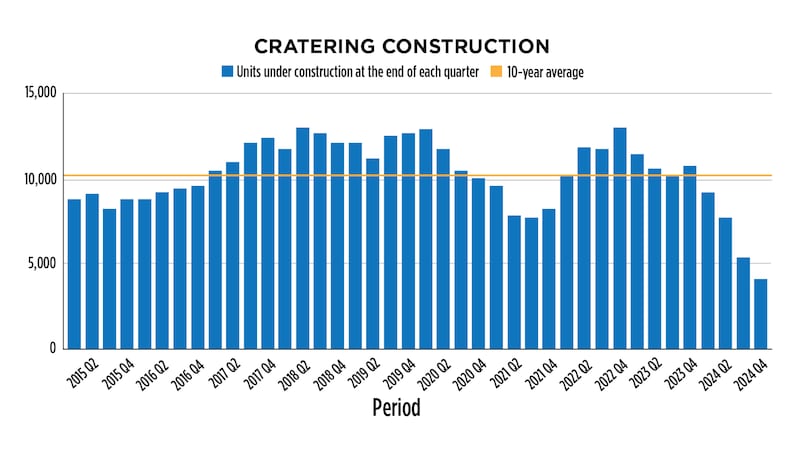

A look at the data shows why they’re lashing the industry to do more. Last year, apartment construction in Portland metro area fell to levels not seen since 2013, according to statistics collected by CoStar, a real estate information firm based in Arlington, Va. (see chart, below).

The number of apartments under construction tumbled every quarter last year, hitting just 4,375 in the final one, far below the 10-year quarterly average of 10,374.

So what’s the problem? Developers who build apartment buildings and brokers who sell them describe an unfortunate confluence of events. The worst one: Interest rates ran up after the pandemic as government cash coursed through the economy and a shrinking supply of workers demanded higher wages to do tough post-COVID jobs, like nursing.

But Portland has some self-inflicted wounds, they say. The city put inclusionary zoning rules in place in 2017, requiring any new apartment building with 20 units or more to set aside 20% of them for people earning 80% of the area median income. Alternatively, developers could reserve 10% of units for renters who make less than 60% of the median.

Whichever adventure they choose, the requirement diminishes the revenue from rent that a building can collect. Developers adapted in a few ways. First, they got approval for buildings before the inclusionary rules went into effect. That’s why we saw so many cranes on the city skyline for several years. Second, they started maxing out buildings at 19 units to avoid the hit to rent.

“We’ve seen a bunch of buildings that are 19 units or fewer,” says Greg Frick, co-founder of HFO Investment Real Estate.

That’s bad, Frick says, because developers are putting just 19 units on parcels of land that could support many more, thereby cutting the new supply that Kotek wants.

“If you want the private sector to build housing, you can’t keep setting up these hurdles,” Frick says. “You’re not making a compelling case to invest here.”

Tom Brenneke, president of Guardian Real Estate Services, agrees. Many apartment complexes are funded by investors from beyond Portland, and Brenneke says they have soured on the city in part because of the changeable nature of its housing policy. A recent one that’s spooking them: Oregon’s move in 2019 to become first state in the nation with statewide rent control.

“Institutional capital stays really far away from rent-controlled states,” Brenneke says.

In terms of completions, CoStar expects to see Portland gain a total of about 5,000 apartments in 2025 and 2026, the weakest two-year stretch since 2012 and 2013.

The upside for developers, according to CoStar: A dearth of new apartments means the vacancy rate, running about 7.5%, has likely peaked. But that’s bad news for tenants: CoStar forecasts that year-over-year increases in rents could approach 3% by the end of this year. Portland hasn’t seen annual growth above 2% since early 2023, CoStar says.