Last week, the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Transportation released its long-awaited funding proposal for the Oregon Department of Transportation.

The proposal, which would raise nearly $1 billion a year, includes a slew of ideas, such as higher title and registration fees, a sales tax on vehicles, a road-use charge on delivery vehicles, and gradually moving all electric vehicles into a pay-per-mile program (“Supercharger,” OJP, April 2). It also features a 20-cent-per-gallon gas tax increase, phased in over six years. That would increase the gas tax from 40 cents per gallon to 60 cents, a 50% increase. (California’s current tax is 68 cents; Washington’s is 53 cents.)

A November report ODOT produced in preparation for the funding package, however, shows that the gas tax does not fall equally on all Oregonians.

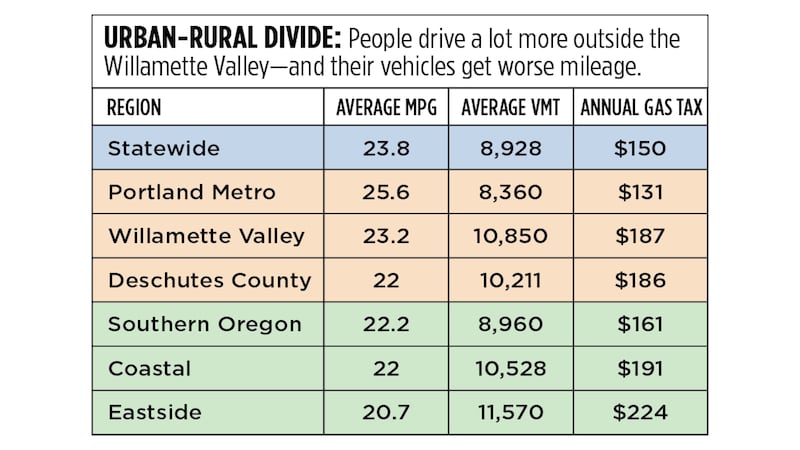

Drivers in rural Oregon, the agency’s data shows, drive far more miles than urban Oregonians and do so in vehicles that travel fewer miles per gallon of gas.

“Rural residents drive farther to get to work, school or shopping,” says state Rep. David Gomberg (D-Otis), whose district includes the central coast and Coast Range. “And we drive less fuel-efficient vehicles. Because the fact is that there are more pickup trucks in Otis than there are in the Pearl District.”

Indeed, ODOT’s numbers show that rural Oregonians pay more in gas taxes than urbanites, with the biggest difference between those living east of the Cascades, who pay 71% more than people in the Portland metro area (see table, below).

Oregon built its gas tax system on a “user pays” principle, although as the Oregon Journalism Project has reported, the Legislature has failed its constitutional duty to equalize payments from passenger vehicle owners, who have underpaid in recent years, and heavy-truck owners, who have overpaid (“Shell Game,” OJP, Feb. 26).

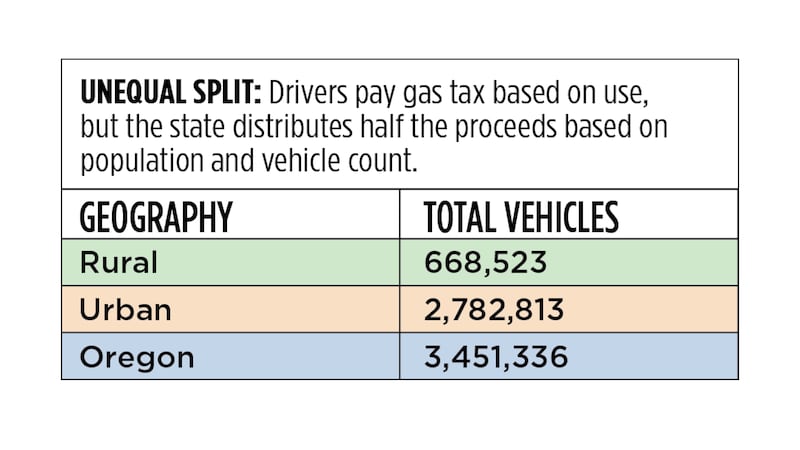

But the formula by which the Legislature distributes gas tax dollars penalizes rural Oregonians (see table, upper right). ODOT gets half the proceeds; 30% gets distributed to Oregon’s 36 counties, based on the number of vehicles registered; and 20% goes to cities, based on population.

“This system ignores that rural drivers pay more in gas taxes yet receive less in return for road funding,” Crook County Commissioner Seth Crawford says. “It’s frustrating.”

The state’s most populous counties, which include its largest cities, get the lion’s share of the money the state distributes, even though their residents drive relatively less. (There are offsetting examples in other areas; income taxes from the Willamette Valley, for instance, subsidize rural residents.)

Gomberg says this legislative session is an opportunity for the Transportation Committee, which also says it hopes to equalize the payment balance between light and heavy vehicles this year, to fix the urban-rural imbalance.

“As long as we’ve had the gas tax, we’ve had this problem,” Gomberg says.

Transportation Committee co-chair Rep. Susan McLain (D-Hillsboro) notes that while rural motorists pay more in taxes, they also benefit more from ODOT plowing and maintenance work. But she and co-chair Sen. Chris Gorsek (D-Gresham) pledge to make the system more equitable. “As part of the ongoing conversations around this package, relief for low-income drivers (especially in rural communities) will be a North Star that we take very seriously,” Gorsek says.

This story was produced by the Oregon Journalism Project, a nonprofit newsroom covering Oregon.