Three years is a long time in the course of someone’s health. Leave tuberculosis untreated and it will kill you in three years. Ignore asthma for that long and it can create permanent lung damage. Ignore diabetes for three years and you risk kidney damage and heart disease.

Three years makes a big difference for hospital systems, too.

In May 2022, the board at Legacy Health, a Portland-based company with six hospitals and more than 14,000 employees, decided it would be wise to team up with another player. It’s easy, in retrospect, to see why. The hyper-infectious Omicron variant of COVID-19 was sending more very sick people to hospitals, raising their costs, and delaying far more profitable surgeries.

Crosstown rival Oregon Health & Science University got wind of Legacy’s urge to merge and pitched Legacy’s board on a combination in December 2022, according to a timeline of the transaction submitted to state regulators. In August 2023, the institutions signed a nonbinding letter of intent for OHSU to purchase Legacy and announced their intentions to the world.

A merger would make OHSU, already the biggest employer in Portland, even bigger, with 32,000 doctors, nurses and nonmedical staff, 12 hospitals, and 3 million patient visits a year. Unlike Legacy, Kaiser or Providence, OHSU is a chimeric “public corporation” that collects government money ($136 million in the last biennium) and enjoys protection from large medical negligence suits. The governor appoints members to OHSU’s board, the state Senate confirms them. The board hires the university’s president, who runs the place like any other hospital chief executive.

As part of the purchase, OHSU said it would raise $1 billion in the bond market and plow desperately needed cash into Legacy’s aging hospitals. It seemed a smart move. Legacy lost $172 million from operations in the fiscal year that ended March 31, 2023. Legacy said in its pitch to regulators that if OHSU didn’t buy it, a rapacious, cost-cutting private equity firm would.

In an interview last week, OHSU interim president Steve Stadum told WW that a deal remains necessary to keep Legacy from getting picked off—and picked over. Among the many upsides: A purchase by OHSU would bring Legacy under the state statute that requires the university to hold open meetings and undergo state audits.

“This will bring more daylight to health care decision-making than Oregon has ever seen,” Stadum said. “OHSU is a big entity that has screwed up at different times, but we are accountable and we answer to the public. That isn’t going to happen at Legacy if it’s acquired by an out-of-state company or a private equity firm.”

Stadum, a lawyer by training, drove the development of the South Waterfront and the Portland Aerial Tram. By all accounts, he has righted OHSU’s ship after a stormy six-year voyage under former president Dr. Danny Jacobs.

But the hundreds of pages of documents describing the Legacy deal, and interviews with health care experts and OHSU insiders, reveal the picture looks different today than it did three years ago.

OHSU, once the solvent, respected savior, has been tarnished by mismanagement, the pandemic, and Donald Trump. Marquee scientists have left their posts. Top executives have departed under clouds. The Trump administration is trying to strip away millions in research funding. And animal rights activists are drawing powerful allies into their fight to close OHSU’s Oregon National Primate Research Center.

People who know health care have come out against the deal. John Kitzhaber, the medical doctor and three-and-a-half-term governor who freed OHSU from a good deal of state control by making it an autonomous public corporation in 1995, says the team that cooked up this deal hasn’t made a case for it.

“There has been no clear articulation of why this transaction will be in the public interest,” Kitzhaber wrote on his blog in November. “Not only in the interest of Oregon consumers, but also in terms of addressing the larger challenges facing Oregon’s health care system.” Among them, Kitzhaber wrote: rising insurance premiums and a crisis in primary care.

Teresa Goodell agrees. A trauma nurse who earned a Ph.D. at OHSU in 2004 and taught there for eight years, she served on a community review board advising state regulators on the merger. She and her colleagues unanimously rejected it in a vote on April 7.

“Prices will inevitably increase,” Goodell said after the vote. “All the literature shows that’s what happens. Increasing prices reduce access and, therefore, affect equity.”

Two Oregon agencies must bless the deal before it can happen. The Oregon Health Authority can approve the merger, approve it with conditions, or reject it. The Charitable Activities section of the Oregon Department of Justice is scrutinizing the deal, too.

From a health care perspective and an economic one, the proposed merger is a matter of huge importance. Which is why we are providing this list of eight things we think you should know about the biggest health care deal in Oregon history.

1. Legacy Health is in better shape than it lets on.

If you think brain surgery is complicated, try making sense of Legacy’s financial statements.

In a filing with the state, OHSU says Legacy lost $96 million in the fiscal year that ended March 31, 2024. But in the audited figures Legacy makes public, it says it turned a profit from operations of $16.5 million, just one year after losing $171.7 million. (It’s possible that the difference could be explained by Legacy getting a one-time cash bump of $98.3 million from selling its laboratory operations. But even then, the figures don’t match. Neither Legacy nor OHSU could explain the discrepancy.)

Bottom line aside, Legacy said its “patient service revenue,” something that is very unlikely to include one-time gains, rose 8% to $2.6 billion.

That turnaround is important because OHSU, Legacy and its labor unions have argued that if this deal doesn’t go through, Legacy could attract a greedier suitor.

“Simply put, Legacy Health must find a strategic partner to achieve financial sustainability, and OHSU is the best possible partner for Legacy Health,” OHSU said in the 60-page description of the deal it sent to OHA’s Health Care Market Oversight program in September.

It’s correct that Legacy suffered during the pandemic because people stopped coming in for expensive elective surgeries and delayed necessary ones that weren’t urgent. So did OHSU, which has recorded losses recently, too.

Costs went up because hospitals had to pay more to keep nurses, many of whom quit after taking lip, or worse, from angry, sick, entitled patients. But Legacy, a nonprofit hospital system, has shown an operating loss in just one of the past six years: 2023, when it lost that $171.7 million.

Recently, two big bond-rating agencies have issued upbeat reports on Legacy’s ability to pay interest on its debt. Moody’s affirmed in December the hospital system’s “A1” investment grade rating, asserting that Legacy would continue to benefit from “good market share in metro Portland, Oregon; good organizational size and footprint; a strong network of clinics and relationships; and very strong clinical offerings.” S&P Global Ratings followed suit April 11.

Rebound aside, OHSU says, Legacy must also spend as much as $750 million on capital improvements, and it has $25 million in deferred maintenance.

Hayden Rooke-Ley, a fellow at the Brown University School of Public Health in Providence, R.I. (and a native of Eugene), thinks OHSU and Legacy are crying wolf. Legacy has a healthy 187 days of cash on hand, according to S&P. Its pension plan is overfunded. Long-term debt is falling from a peak in fiscal 2023, and it has an investment portfolio worth $1.3 billion.

“The parties are presenting the acquisition as a binary choice: either the state approves the OHSU acquisition, or Legacy is sold to an out-of-state, for-profit owner,” Rooke-Ley and three colleagues from Brown and the University of California wrote in a public comment to HCMO. “Legacy appears to have recovered from the pandemic and to be on sound financial footing.”

2. In the past three years, the administration at OHSU has been anything but stable.

Danny Jacobs was at the helm when OHSU proposed buying Legacy back in August 2023. He’s gone now. So is OHSU board chair Wayne Monfries. Neither man is missed, according to most OHSU leaders and, especially, rank-and-file workers.

Trouble had been brewing on Pill Hill for a while, but one of the first documented signs of discontent emerged in the summer of 2023, when OHSU polled its 19,369 employees. One of the questions: Would you stay at OHSU if offered a similar position elsewhere? Just 54% said they would. Worse yet, 44% said they had no confidence in senior management. About a third were neutral on that question, and another third had “unfavorable” opinions.

Heads started rolling soon after. In June 2024, a series of management blunders prompted Jacobs to push out the human resources chief he had brought in 20 months before to fix discrimination, harassment and bullying described in the $6.5 million Covington Report, commissioned after a resident with a huge following on TikTok sent a female colleague a photo of his penis and crept up behind her with an erection.

Jacobs himself resigned four months later after irking staff with a plan to pay top managers cash bonuses untethered to performance, excluding union workers, and collecting for himself an extra $700,000 in retirement money (approved by Monfries alone) while cutting staff.

Then in December, Dr. Brian Druker, the rock-star Oregon scientist who put OHSU on the map by basically curing leukemia, left his post atop the Knight Cancer Institute, a $1 billion enterprise funded by Nike founder Phil Knight and his wife, Penny, with matching funds from the state and other donors. OHSU had “forgotten” its mission, Druker said on the way out, and was no longer a place to do cutting-edge research.

Legacy lost its merger-boosting CEO, too, when Kathryn Correia retired. Board chairman Charles Wilhoite is still there. He’s the biggest proponent of selling Legacy, according to two people familiar with the matter who declined to be named. He’s the “dealmaker,” one said.

Wilhoite didn’t return a message sent on LinkedIn.

3. The Trump administration wants to gut OHSU’s research budget.

If OHSU was once the richer partner in this marriage, that’s no longer so obvious. After struggling through the pandemic, the university got word in February of more money woes.

In the world of scientific research, in addition to grants for medical studies, there are grants for “indirect costs.” This is extra money the National Institutes of Health and foundations pay, alongside grants, to cover overhead: things like heat, electricity, and paperwork for enrolling patients in clinical trials.

Each academic medical center negotiates its own matching rate for indirect costs, based on what kind of research it’s doing. “Wet” research, which involves people and animals, has higher indirect costs than research done by crunching data on a computer. OHSU’s matching rate for indirect costs is on the high side, at 56%.

In February, the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency, led by space billionaire Elon Musk, announced it was cutting coverage of indirect costs to 15% for all institutions. OHSU says that would be a death sentence for most of its research.

The university got $277 million from the NIH last year. At the 56% matching rate, about $177 million of that figure went to direct costs, and about $100 million came in for indirect ones. At 15%, grants for indirect costs would bring in just $27 million, a loss of about $73 million, OHSU has said.

“Even at 56%, indirect costs do not cover the full cost of supporting each research grant,” President Stadum wrote in a letter to staff in February.

State attorneys general, including Oregon’s Dan Rayfield, took the administration to federal court in Massachusetts and won a permanent injunction against the cuts, but the litigious Trump team is expected to appeal.

4. The politics of the primate center have never been more divisive.

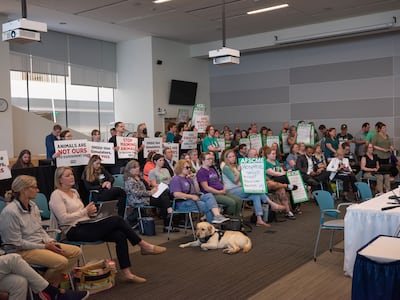

Animal rights activists have been pressing OHSU to close its primate research center in Hillsboro for years. They amped up their efforts this year with a media campaign, betting that regulators might lean on OHSU to stop primate testing as it seeks to buy Legacy.

On March 27, Gov. Tina Kotek told WW she wanted to close the Oregon National Primate Research Center after years of citations for maiming and killing macaques and other primates there, never mind the 900 euthanized each year in the course of legitimate research.

Quality of life for monkeys isn’t one of HCMO’s criteria for approving health care mergers, but the furor over the primate center tarnishes OHSU’s image as it seeks to gobble up a competitor.

The primate center brings in about $56 million in NIH grants every year and employs about 400 people, including 170 union members, a key constituency for Kotek and, by extension, OHSU. The more union staff there is at the university, the more pull its unions have in Salem.

Activists have kept up the pressure. Last week, a staffer at People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals wrote to the National Institutes of Health, urging it to investigate violations of rules that allegedly led to the Oct. 2 death of a macaque at the center.

More threatening than PETA is the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, run by Robert F. Kennedy, a skeptic of vaccines and a man with a keen interest in animals. Kennedy’s deputy at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is Johns Hopkins University surgical oncologist Martin Makary, who said this month the FDA would phase out requirements for animal testing on some drugs, replacing them with computer models.

5. Even proposing a merger has been good for the unions.

Legacy was never much of a union shop, unlike OHSU, whose doctors, nurses and staff are represented by two large unions and their affiliates. But when the proposed takeover was announced, the Oregon Nurses Association and Northwest Medicine United stepped up organizing at Legacy, talking about the need for protection from layoffs that would be an inevitable result of the merger. Now, unions represent 37% of Legacy’s 14,000 workers, including doctors, who are new to the labor movement, up from 10% before.

“Legacy has a history of not treating their front-line health care workers with the respect they deserve,” says Kathryn Geren, a nurse in Legacy Emanuel’s cardiovascular intensive care unit.

OHSU, by contrast, has gone to great lengths to keep the unions happy. Not long after the merger announcement, Jacobs promised all union workers 12 months of guaranteed employment if the deal closed. Nonunion workers got just a six-month guarantee, according to a September email obtained by WW at the time, which caused further turmoil.

The upshot? Labor costs are likely heading up.

6. If regulators approve the deal, at least two experts think, the cost to remove your gallbladder could rise by 6% the first year.

OHSU says the Legacy deal won’t boost medical bills any more than if no transaction were to occur, even though care would be concentrated in fewer hands, a proven recipe for price increases. And OHSU says pointing to other mergers is not useful.

Because of the university’s status as a public corporation with a different mandate than other hospital systems, “OHSU’s proposal to integrate with Legacy is different than any other health care merger in the state or country, and it is impossible to draw conclusions about the effects of the OHSU-Legacy integration based on general findings from national research about typical health care mergers,” OHSU and Legacy said in a letter to OHA in January.

Martin Gaynor, a professor at Carnegie Mellon, and Barak Richman, a professor at George Washington University, who produce national research on trends in health care mergers, say otherwise.

“The parties’ this-time-is-different argument seems to rest on the notion that OHSU is a quasi-public institution and therefore will not abuse its market power,” Gaynor and Richman write. “But there is overwhelming evidence that consolidation reduces competition and increases costs—whether or not the consolidating parties are for-profit or not.”

Based on national averages, Gaynor and Richman say the result will likely be a 6% spike in costs in a year, “with continual price increases for at least two years post-merger.”

7. There is a reason trial lawyers don’t like the merger.

Being a quasi-governmental agency like OHSU has its rewards. One of them is that damages for medical negligence in one of its operating rooms are capped by state law.

As part of OHSU, Legacy would enjoy the same protections. Like every hospital system, Legacy faces countless negligence suits every year. It faces a gigantic one now.

The parents of Legacy Good Samaritan security guard Bobby Smallwood sued the hospital for negligence, seeking $35 million, in November, saying Legacy endangered him by ignoring its own violence protocols. Smallwood was shot and killed in 2023 by PoniaX Kane Calles, who had threatened hospital staff repeatedly in the days before the shooting.

If it were part of OHSU, the maximum Legacy would pay in negligence cases is $2.6 million because damages against state agencies are capped by Oregon law.

Trial lawyers, who most often get paid out of settlements and judgments, say damage caps discourage them from even filing because the cases are expensive to pursue. They also skew the legal system in favor of medical providers and away from judges and juries, lawyers say.

“Caps take the power away from juries to decide on a case-by-case the merits of the case,” the Oregon Trial Lawyers Association said in a comment filed with HCMO.

Worse yet for patients, at OHSU they must file notice that they plan to sue within 180 days of an injury, or within a year after a death. At Legacy, patients have two years.

Whatever the reason, OHSU faced only four medical negligence claims in Multnomah County Circuit Court in 2024, compared with 30 for Legacy Health.

8. Federal antitrust regulators get no say on the deal.

OHSU was a state university until 1995, when it became a “public corporation,” a public-private entity that gets money from the state but also has considerable autonomy from it.

The odd status has benefits. The U.S. Supreme Court has held that federal antitrust laws don’t override state laws. In the case of public entities like OHSU, state legislatures can inoculate public entities from federal review by expressing their intent to protect them. The Oregon Legislature did just that in 1995 with a gumbo of legalese.

As a result, even if there are legitimate antitrust concerns, that would not prevent a merger.

That leaves just two regulators examining OHSU’s purchase of Legacy: HCMO and the Charitable Activities section of the Oregon Department of Justice. Though both examinations could raise red flags about market power, neither are expressly aimed at stopping a monopoly in Portland’s health care market, according to Rooke-Ley and his team at Brown University.

The mission of HCMO, set up in 2022, is to make sure deals like this one lead to more health equity, lower costs, increased access, and better care. DOJ’s Charitable Activities, which began its 60-day review on April 1, must determine only whether the merger serves the public interest.

The DOJ is also looking at a related transaction: Legacy seeks to transfer its 50% stake in insurer PacificSource to the Legacy Health Foundation, which would be spun off as an independent entity. Legacy would also transfer a portion of its cash to the foundation, according to a formula described in a document that is completely redacted, save for a title and one paragraph. Legacy says the amount is expected to be about $350 million.

Dr. John Santa, an Oregon health policy expert who trained at Legacy’s Good Samaritan Hospital and worked for both OHSU and Legacy, says the public needs more information on the transfer, and why two hospital systems that are strapped for cash are making it.

“Follow the money—at least to the degree the information allows you to,” Santa wrote in a comment to HCMO. “You will see hundreds of millions of dollars moving around. I think figuring out where all the money goes in the middle of this deal is next to impossible.”

So far, OHSU is striking out with regulators. On April 7, a community review board comprising Oregon citizens to advise HCMO recommended by a unanimous vote rejecting the Legacy deal. The review board has no power to block the merger, but HCMO is supposed to take its opinion into account.

It’s clear who has the final say at the DOJ. That’s Attorney General Dan Rayfield. At OHA, it took several inquiries, and more than one read of the legislation that created HCMO, to determine who makes the call. That would be OHA director Dr. Sejal Hathi, who reports to Kotek.

“When we can’t figure out who is actually making a decision, there is something wrong with a government program,” Santa says.

Both Kotek and Rayfield relied heavily on labor money and union endorsements to secure their offices in recent elections. The unions really want this deal, in part because Legacy would become part of a very union-friendly OHSU.

Kotek spokesman Lucas Bezerra says his boss “has no statutory authority on the final decision” but “has closely watched the merger review process.” The governor has not said whether regulators should approve the deal or not.