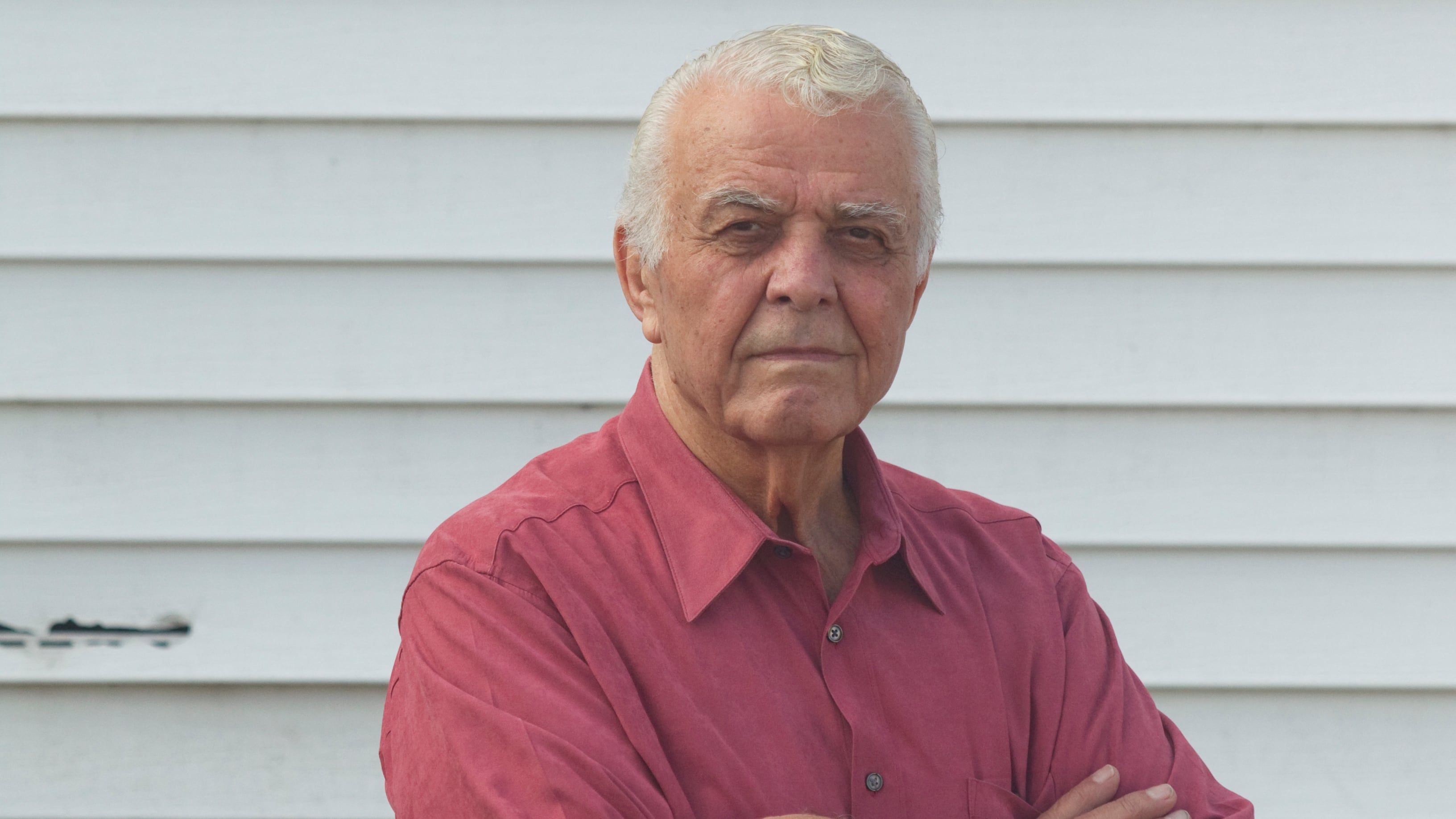

Theodosios “Saki” Tzantarmas, a Greek immigrant who built a nightlife empire at the edge of Portland and for decades resisted city efforts to gentrify his neighborhood, is dead at 81.

Friends and family confirmed Tzantarmas’ death this morning. The cause was not announced.

Tzantarmas purchased a bar on Southeast Foster Road in 1972 and named it the New Copper Penny. Over four decades it grew to take up a full city block, encompassing a banquet hall, off-track horse betting parlor, a nightclub and a family restaurant.

The Penny’s huge neon sign became the most iconic landmark in East Portland. But the bar was at times a bane to neighbors and police, who described it as a magnet for violence.

For at least a decade, Tzantarmas negotiated with the Portland Development Commission (now Prosper Portland) over redevelopment plans for the Lents neighborhood. Those plans sometimes included a revamped New Copper Penny, and at other times hinged on Tzantarmas closing up shop, at a multi-million dollar price. (Negotiations often turned hostile: At one juncture, Tzantarmas claimed a city official had called his family “terrorists holding the neighborhood hostage.”)

Last year, Tzantarmas sold to a real-estate developer who plans to turn it into an apartment building. He later tried to open a new edition of his bar, across the street.

Here’s how WW described Tzantarmas in a 2014 cover profile.

"This man," says daily patron Nick Raptor, stretching out his arms, "his heart is this big."

Tzantarmas has the long, dangling arms of a former prizefighter, and a pugilist's face: deep bags under his eyes, a pug nose and toothy grin. He wears bright pastel sweaters and gray slacks, and talks in a thick Macedonian accent.

The New Copper Penny is a sprawling enterprise. One wing has a dance floor, another a room with television screens showing horse races. On the east side is a recently remodeled restaurant with a stainless-steel counter. When Saki first bought the place in 1972, he served gyros 22 hours a day. Now the restaurant has 22 taps of Northwest craft beers.

At breakfast, Tzantarmas holds court, busting the chops of whoever's sitting nearest. When he teases, his deep-lined face breaks into a huge, mischievous smile. "He has this thing now where he tells me he only loves me on Tuesdays," says Nikki Tzantarmas, his 23-year-old daughter, who tends the New Copper Penny's bar. "I'll say, 'I love you,' and he'll say, 'I don't.' He'll never get old. Ever."

Nikki shows a faded photograph of her father folk dancing, holding aloft a table—covered with a cloth and cluttered with bottles of wine and ouzo—with his teeth.

"You don't want him to bite you," Raptor says.

The legend of Saki is passed down orally and in writing—on the old plastic menus the New Copper Penny only recently replaced.

It tells how Tzantarmas' father, a Greek army officer in Thessaloniki, was killed by Communists in the 1950s ("they chopped him up," Tzantarmas says, sliding a finger across his throat) and how the son spent three years in an orphanage and a year at sea before jumping ship in Philadelphia with five pennies in his pocket.

He arrived in Portland as a heavyweight boxer, with a gold medal he claims is from the 1959 European Championships. In a 1965 bout, The Oregonian billed him as "the Golden Greek of Portland." (He lost on a technical knockout in the third round.)

After six years he says he spent working as a folk dancer, Tzantarmas purchased a run-down pub called the Copper Penny in Lents, his home neighborhood. He soon bought all the properties on the block. A hardware store became the nightclub, a doctor's office the restaurant, and a shuttered movie theater the Parthenon.

The New Copper Penny became East Portland’s go-to spot for nightlife: bikini contests with cash prizes on Thursdays, Top 40 dance nights with a fog machine, and, on Sundays, “Greek Nights” when Tzantarmas can still be found sitting at the central table, singing along to the folk songs and showering a belly dancer from a stack of $1 bills.