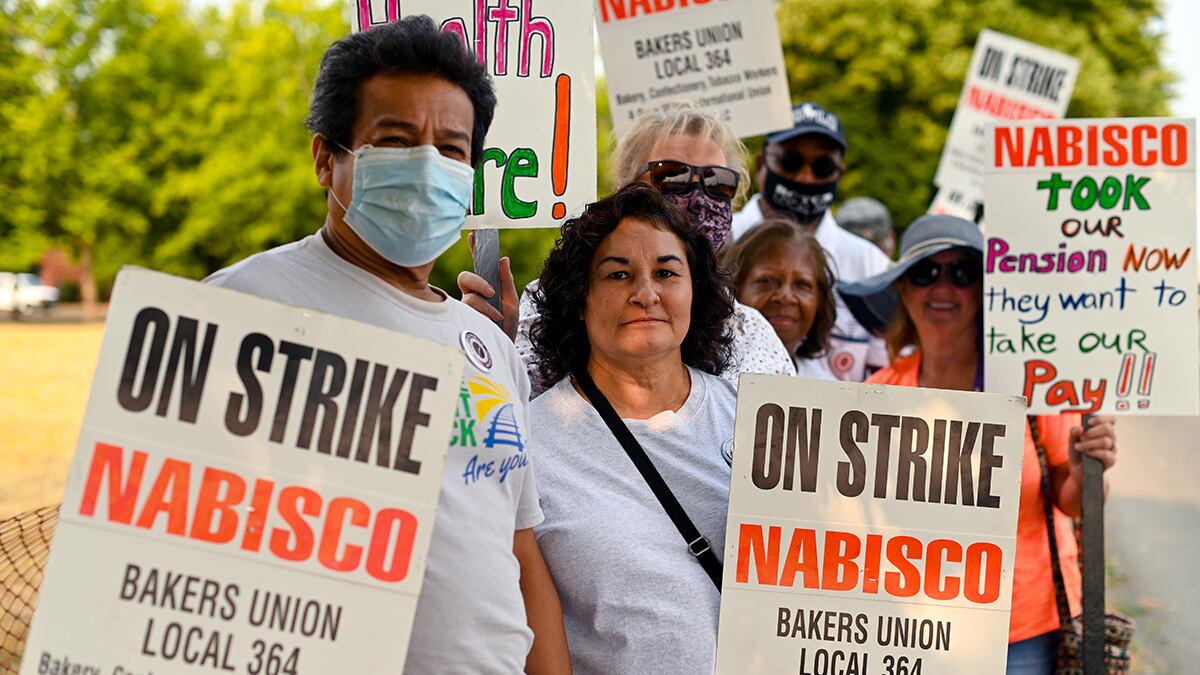

Last week, more than 200 Nabisco workers in Northeast Portland walked out of their cookie and cracker factory and onto a picket line—launching a strike that has since gone national.

WHO WENT ON STRIKE

The 200 workers are part of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers’ International Union Local 364. On Wednesday, about 15 union members held signs that read “Nabisco: Killing America’s Middle Class” and “Oreo is on strike.”

WHAT THEY MAKE

The Nabisco bakery along Northeast Columbia Boulevard—tucked behind several fast-food restaurants at the intersection with Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard—produces Oreo and Chips Ahoy! cookies and Ritz, Premium saltine and Chicken in a Biskit crackers. It occasionally fills the nearby Woodlawn neighborhood with the smell of melting chocolate. It is owned by Chicago snack giant Mondelez International.

Union vice president Mike Burlingham says nothing new is being produced at the bakery during the strike, but cookies and crackers already packaged are still being loaded onto trucks. “At this time, there aren’t any lines running,” Burlingham says.

But Mondelez begs to differ, telling WW it has a contingency plan to produce Oreos during a strike. “We have activated that plan and are committed to continuing to supply our delicious snacks to retailers and consumers,” a company representative said. The company did not share the details of that contingency plan.

WHAT THEY WANT

The workers plan to strike until the company agrees to negotiate a new contract, says Burlingham.

One of the issues is a proposal by Mondelez to eliminate overtime pay for working on the weekends by altering the schedule to incorporate weekends into the 40-hour work week.

Donna Marks has worked at this facility for 17 years in environmental health services. She says after the Nabisco brand was absorbed by Mondelez in 2012 after Kraft Foods split into two entities, one being Mondelez, “the environment changed.”

“I used to enjoy this job, it used to be like a family to me. Now, they want us to work more and pay us less, and everything that we have, we have because we negotiated,” Marks says. “They want to take away what we fought for with no negotiation. They act as if they gave us something.”

WHY IT MATTERS

Portland was the first of Nabisco’s facilities across the country to strike. Since then, workers at a bakery in Richmond, Va., and a sales center in Aurora, Colo., have gone on strike, too. (Other unions in the Portland facility—including the machinists, electricians and operating engineers—are honoring the picket line.)

The labor dispute follows years of Mondelez cutting employee pensions and halving its unionized workforce by closing bakeries in New Jersey and Atlanta. That leaves just three Nabisco bakeries operating in the U.S.: in Portland, Chicago and Richmond.

So what happens on this Northeast Portland sidewalk has significant implications for who will make Ritz crackers in the coming decades.

On Aug. 13, the company fenced off the entire property with orange vinyl fencing, pushing the strikers closer to Columbia Boulevard, a thoroughfare for big trucks and speeding cars.

“It’s definitely an intimidation thing,” says Burlingham. “We’re getting sandblasted on the sidewalk as truckers blow by.”