Robert Boisseau Pamplin Jr. casts a large shadow over the state of Oregon and beyond.

The Pamplin School of Business at the University of Portland bears his name; so does the athletic center at Lewis & Clark College. In Virginia, there is a $40 million Pamplin Historical Park and a Pamplin School of Business at Virginia Tech.

Pamplin, 80, is president of R.B. Pamplin Corp., a sprawling and family-owned enterprise that includes a string of Southern textile mills and, in Oregon, an 81,000-acre cattle ranch, a vineyard and a 900-acre Yamhill County farm. For many years, Pamplin was a fixture on the Forbes list of the 400 wealthiest Americans. In Portland, his company owns Ross Island, the leafy, crescent-shaped archipelago that splits the Willamette River downtown and is a magnet for kayakers.

Also in the R.B. Pamplin Corp. portfolio: the state’s largest news organization, with 24 papers that include the Portland Tribune.

“No individual in Oregon has done more to support local journalism than Dr. Robert B. Pamplin Jr.,” says Mark Garber, president and publisher of the Pamplin Media Group.

Yet, as the Tribune celebrates its 21st birthday this month, interviews and a review of public records paint a picture of a crumbling empire. That decline, some experts believe, may be jeopardizing the pensions of nearly 2,400 current and former R.B. Pamplin Corp. employees.

A three-month investigation by WW found:

- More than four dozen lawsuits filed in state and federal courts in recent years against Ross Island Sand & Gravel and other R.B. Pamplin Corp. companies for unpaid bills.

- Tax liens filed by federal, state and local governments against three of R.B. Pamplin Corp.’s companies and, briefly, by the state of Oregon against Pamplin himself for failure to pay state income taxes. (Many liens have now been released.)

- The Pamplin companies’ recent and, experts say, highly unusual sales and contributions of his companies’ real estate to his employees’ pension fund. Those transactions appear to shift risk to pensioners and funnel cash to Pamplin operating companies. And, according to pension experts WW spoke with, some of the transactions may violate federal pension law.

One of those experts, Terry Deneen, a fellow at the Washington, D.C.-based Pension Rights Center, examined a number of those real estate transactions and went so far as to say there appears to be a “systematic looting of the pension plan.”

“I can’t believe he’s getting away with it,” Deneen says.

WW reached out to Pamplin on Feb. 2 and, after he declined an interview, submitted written questions on Feb. 6. Two of his top executives, Garber and R.B Pamplin Corp. chief financial officer Andrea Marek, responded to questions about financial issues to say that Pamplin, R.B. Pamplin Corp. and its subsidiaries have acted legally and honorably in all instances, including the real estate transactions.

“During COVID, there was great disruption, not just for us, but for everybody,” the executives say. “We have addressed these issues, and they have been resolved or are being successfully managed. Through hard work and diligence, our companies have emerged stronger and are growing through acquisitions.”

One interested stakeholder: Gary Nordby, a 73-year-old retiree who spent 35 years working for a local R.B. Pamplin Corp. paving company.

Nordby had no idea that Pamplin’s companies transferred real estate to the pension fund.

“This is the first I’ve heard of it, and I don’t like the sound of it,” says Nordby, whose gravelly voice reflects decades of inhaling sulfurous asphalt fumes. “I don’t want to get screwed out of my pension—I worked hard for it.”

Robert Pamplin Jr. was born into a family of extraordinary wealth. From the 1950s through ‘70s, Pamplin’s father, Robert Pamplin Sr., built Georgia Pacific, then headquartered in Portland, into one the nation’s largest publicly traded forest products companies.

The private company he founded, R.B. Pamplin Corp., also bought Oregon companies that included Ross Island Sand & Gravel and built one of the nation’s biggest privately held textile companies, South Carolina-based Mount Vernon Mills.

The elder Pamplin had only one child, Robert Jr., who, after graduating from Lincoln High School and Lewis & Clark College, soon joined the family enterprise.

The younger Pamplin added more businesses to the family holdings: a Christian music company and bookstore chain, farming and ranching operations, radio stations and newspapers.

Today, the front page of every Pamplin newspaper and every online news story features a thumbnail illustration of a smiling Pamplin alongside the caption: “Owner and neighbor, Dr. Robert B. Pamplin, Jr.” (His two doctorates are from an online, for-profit school and Western Seminary on Southeast Hawthorne Boulevard.)

Pamplin’s 10-page résumé includes, in granular detail, a summary of his physical accomplishments (“able to do 500 push-ups, 75 chin-ups, and 1,000 sit-ups”) and offers examples of his adventures: “Escaped Kenya tribal war and killed a charging buffalo.”

Pamplin, an ordained minister who says he’s written 44 books, also produced two feature-length films about his family. He hired Hollywood actors Hal Holbrook and Corbin Bernsen for key roles in A Place Apart, a 1999 biopic of his travails at Virginia Tech (he left after a year of hazing), and also made The Other Shore: An American Journey, which is billed as the “1000-year family saga of the Pamplin family.”

Despite his philanthropy and multimedia interests, Pamplin remains relatively unknown both by employees and by people in his professional and social spheres.

After Pamplin launched the Tribune in 2001, he occasionally wandered through the newsroom, handing out $50 bills. It was an odd, if welcome, gesture. “Anybody born with that much money is going to be a little eccentric,” says former Tribune columnist Phil Stanford.

Stanford and his former colleagues say Pamplin rarely interacted with newsroom employees after 9/11, which accelerated a decline in print advertising.

Others in the community haven’t seen much of the industrialist either.

“I really thought that Pamplin and I would have had something in common to talk about,” says Columbia Sportswear CEO Tim Boyle. “There’s not a lot of apparel manufacturers in Portland.”

Pamplin and Boyle have also supported many of the same nonprofits. No matter. “I tried to reach out to him a few times but never got anywhere,” Boyle says.

Allen Alley, the former CEO of Pixelworks, an Oregon tech company, and two-time candidate for governor, shares interests and geography with Pamplin: Both are Republicans and, for 23 years, were neighbors in an exclusive Lake Oswego Homeowners Association where Pamplin’s $5.5 million home is one of just a dozen residences.

“He and his wife were very nice,” Alley says, “but they didn’t interact with others much.”

Somewhere along the way, the wheels started to fall off the R.B. Pamplin Corp. empire.

The most obvious problem: the implosion of the U.S. textile business. Over the past 40 years, federal figures show, foreign competition and automation have cost the industry 85% of its U.S. jobs.

R.B. Pamplin Corp.’s Mount Vernon Mills subsidiary used to operate 18 plants. Now, according to its website, the company is down to six. The corporation also closed its Christian music and retail businesses, jettisoned radio stations and, in 2019, auctioned off the fleet of 38 yellow-and-black Ross Island cement mixers that used to roar out of the company’s Southeast McLoughlin Boulevard headquarters like a swarm of bumblebees.

The corporation’s Oregon companies exhibited financial troubles well before the pandemic.

In recent years, for example, dozens of lawsuits targeted Ross Island Sand & Gravel for nonpayment of basic obligations.

In addition to vendors who sued for nonpayment, the federal government has come after Ross Island Sand & Gravel, Pamplin Communications companies, and Columbia Empire Farms for unpaid income taxes. Records show current federal tax liens against Pamplin Communications and its subsidiaries of about $900,000 (see “Lien on Me,” page 16).

The income tax liens—which give the government a security interest similar to a mortgage—reflect unpaid withholding taxes before the pandemic began.

“Failure to pay withholding taxes means he’s absolutely in extremis,” Deneen says. “The red light is flashing that the nuclear power plant is melting down.”

Two top R.B. Pamplin executives—Pamplin Media president Garber and CFO Marek—dispute that.

“Both the R.B. Pamplin Corporation and Ross Island are profitable and have ample funds to take care of financial needs, including lease payments, with no distress,” they say.

Three pension lawyers WW interviewed say the most curious aspect of R.B. Pamplin’s Corp.’s financial dealings may be the way that Robert Pamplin, as the trustee or “fiduciary” for the corporation’s $98.4 million pension plan, is using money set aside for pensioners as a source of cash for the companies.

For one thing, companies the size of R.B. Pamplin Corp. often use independent professionals as trustees to safeguard their pension funds. U.S. Department of Labor filings, however, show Robert Pamplin Jr. serves as sole trustee for his employees’ pension fund.

While there is no law preventing the owner of a company from also being the lone guardian of the company’s employee retirement fund, lawyers say that doing so can create conflicts of interest between requirements of the employer (R.B. Pamplin Corp. and its subsidiaries) and the needs of pensioners.

Robert Pamplin wears both hats: He is president of R.B. Pamplin Corp. and its subsidiaries, and trustee of the companies’ pension fund.

More unusual is R.B. Pamplin Corp. and its subsidiaries’ recent practice of contributing and, more frequently, selling real estate to their employees’ pension fund.

Prior to 2018, the pension plan’s written contribution policy called on the parent company (R.B. Pamplin Corp.) to contribute cash every year to fund its pension obligations. In 2018, records show, that policy changed to allow “cash contributions or property contributions.”

That same year, R.B. Pamplin Corp. stopped contributing cash to fund its retirees’ pensions and switched to contributing real estate.

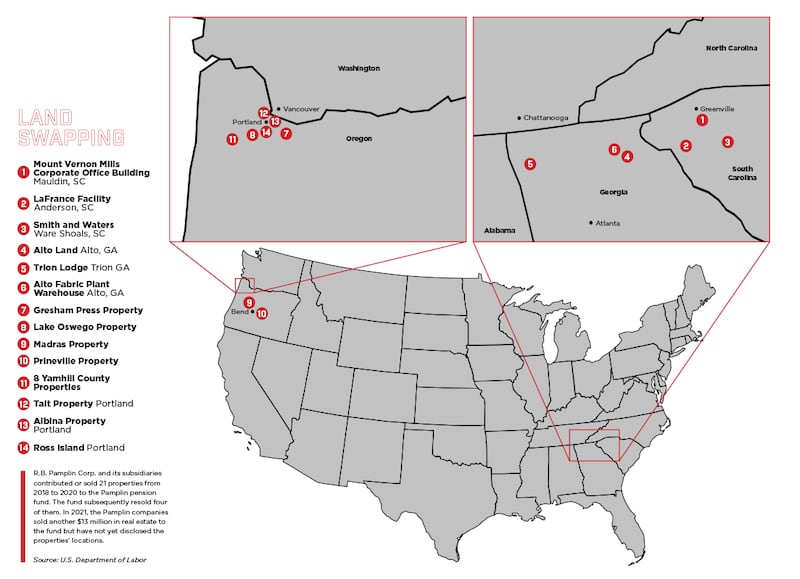

Since then, according to annual filings with the Department of Labor, R.B. Pamplin Corp. and some of its subsidiaries have completed more than 20 real estate transactions with the pension fund, contributing real estate in lieu of annual cash contributions and, more frequently, selling real estate to the fund.

The pension fund now owns two Ross Island Sand & Gravel properties; two former Mount Vernon Mills properties in the South; six winery properties in Yamhill County; and Gresham and Lake Oswego properties formerly owned by Pamplin Communications, among others. (Since the real estate transactions began, filings show, R.B. Pamplin Corp. and subsidiaries have sold $38.3 million worth of property and contributed $10.8 million worth. The pension has resold some $12 million in properties to third parties, leaving $37 million worth of property in the fund, as of Oct. 15, 2021.)

The federal Department of Labor, which regulates pensions, discourages operating companies from doing business with their pension funds.

The selling or contribution of real estate in lieu of required cash contributions to a pension fund by a related party is, according to the Department of Labor, a “prohibited transaction.”

“Plan fiduciaries [such as Robert Pamplin] have an obligation to avoid engaging in ‘prohibited transactions,’ which the statute specifically prohibits, because of the dangers posed by the conflicts of interest associated with such transactions,” says Michael Petersen, a DOL spokesman.

The department does permit such transactions in limited situations, but only if they meet certain criteria and qualify for an exemption.

The accounting firm that prepares R.B. Pamplin Corp.’s annual DOL filings writes, “The Plan Trustee [Pamplin] believes” the property transactions would qualify for DOL exemptions. To qualify, the transactions must represent a fair price and cannot personally benefit the fiduciary.

That belief has never been tested.

“[DOL] has not received an application from nor granted an exemption to the R.B. Pamplin Pension Plan,” Petersen, the DOL spokesman, says.

Garber and Marek insist the real estate transactions are above reproach.

“All of the properties were purchased by or contributed to the plan at fair value, and no personal benefits were received by any plan fiduciary or other person,” they say.

Garber and Marek also note that much of the real estate sold to the pension fund is being leased back by the selling companies at market rates, as the DOL requires.

“The real properties provide an income stream that is greater than the dividends and interest provided from stocks and bonds,” Marek and Garber say. “Also, owner-operated properties used in their business avoids irrational changes in value, and leaseback ensures a steady stream of income.”

Deneen, the pension expert, says the transactions don’t pass the smell test. DOL rules say that no exemption applies unless the fiduciary acts “‘prudently’ and ‘solely in the interest’ of the plan’s participants and beneficiaries.”

For a variety of reasons, Deneen says, the real estate transactions are imprudent.

Real estate, he notes, is illiquid and riskier than bonds and blue chip stocks; industrial property carries environmental liabilities; and the properties are leased back to companies that are shedding jobs and struggling financially.

“It leaves the pension fund with a very high concentration of risk,” he says.

“The domestic textile industry is bust. Print journalism is in terrible shape. His sand and gravel business is mostly closed,” Deneen adds. “He’s sitting on three-legged stool where all the legs have collapsed underneath him.”

One large transaction shows the potential risks that real estate creates for pensioners.

In March 2019, two months after Ross Island Sand & Gravel closed its concrete business, records show, the company sold a closed concrete plant on 2.9 acres at 2611 SE 4th Avenue to the pension fund for $4.8 million cash.

Garber and Marek say the sale was appropriate and legal: “The auditors of the plan and legal experts continue to find no conflict with Dr. Pamplin being trustee and an officer with the R.B. Pamplin Corporation.”

The property, however, was far from the sort of low-risk, blue chip asset the DOL prefers pension funds to own. And the price the pension fund paid to Ross Island Sand & Gravel raised some eyebrows.

The year after RISG sold the plant to the pension fund for $4.8 million, the fund then put the property on the open market at $3.195 million, $1.6 million less than the fund paid RISG for the property.

Even at that price, it didn’t sell.

One prospective buyer, Richard Freimark, tells WW he wanted to buy the property but walked away when he says Pamplin’s broker refused to provide an environmental report or let Freimark do his own environmental testing.

Portland’s industrial waterfront is notoriously polluted, so a buyer would want to know what’s in the dirt after decades of industrial use.

“That was the biggest red flag,” Freimark says. “[The broker] told us they didn’t have the environmental report.”

Garber disputes any information was withheld. “We worked extensively with potential buyers on environmental information,” he says.

The pension fund has now reduced the value of the property in federal filings to $2.5 million. (Garber and Marek attribute the decline in value to a city land use change.)

James Ambrose, a Portland pension lawyer, also reviewed the R.B. Pamplin Corp. pension fund’s 2020 DOL filings, which disclose the sale of the concrete plant and the other property transactions. Ambrose says he found the filings remarkable because the transactions violate settled pension law.

“I am very disheartened that a major company with easy access to sophisticated, competent counsel and accounting expertise has engaged in activity that blatantly disregards the clear rules under which everyone is obliged to comply,” Ambrose says. “One would be hard pressed, to say the least, to even come up with a defensible position to support these actions.”

Another aspect of the R.B. Pamplin Corp. pension fund particularly concerns experts.

Even if the real estate transactions between an employer and its pension fund were to qualify for exemptions, the Department of Labor strictly limits the amount of related-party real estate a pension fund can hold to 10% of the fund’s total assets.

“The purpose of the 10% cap and other limitations is to protect plans from conflicts of interest and from the obvious danger of concentrating too much risk in one company,” the DOL’s Petersen says.

As of the end of 2021, however, federal filings show the R.B. Pamplin Corporation and Subsidiaries Pension Plan and Trust holds real estate it acquired from R.B. Pamplin Corp. and subsidiaries that amounts to nearly 38% of its total assets.

“I don’t see how they could be in compliance with the law,” says professor Norman Stein, who teaches pension law at the Drexel Kline School of Law in Philadelphia.

Petersen, the DOL spokesman, says the consequences for exceeding the 10% cap can include penalties and excise taxes for the trustee and, potentially, undoing the improper transactions.

He declined to comment on specific R.B. Pamplin Corp. pension plan transactions or whether the agency is investigating them.

Garber and Marek say they don’t believe the pension plan’s holdings are improper and insist all of the real estate transactions were legal and prudent and “no monetary penalty is imposed for violation of the 10% real property rule.”

“Most importantly,” they add, “the pension plan has never been late or failed to pay the beneficiaries when due.”

Bill Gallagher, who worked as a radio journalist for Pamplin Communications, is one of the retirees who relies on his monthly Pamplin pension check to make ends meet. He says he hopes his pension is safe.

“I’m counting on the Department of Labor’s rules and regulations,” Gallagher says. “And my belief is that Dr. Pamplin will do the right thing.”

The Sunken Barge

On Oct. 24, 2020, a Ross Island Sand & Gravel dredging barge sank in the San Joaquin River at the Port of Stockton, Calif.

Although Ross Island Sand & Gravel closed Portland concrete operations in 2019, Ross Island remained in the dredging business, deepening navigable waters by scooping material from river bottoms.

For decades, the company has deployed dredging vessels on waters in Oregon and California. But when salvagers raised the sunken Ross Island barge from the bottom of the river, court records show it bore the signs of long-term neglect.

The barge, according to court records, hadn’t been surveyed in almost 25 years, which a specialist who examined it said was highly unusual.

“There apparently had been no inspections or repairs to the hull or internal bulkheads since [1997],” says a complaint filed in federal court in California by the insurance company Starr Indemnity, seeking to recoup $2.6 million in cleanup costs, alleging Ross Island failed to maintain the barge or inform the insurer of its true condition.

Ross Island is contesting the lawsuit, and company officials declined to comment.

No Man Is an Island

Just before Christmas 2021, environmental advocates learned that the state of Oregon had granted Ross Island Sand & Gravel a lengthy extension on its obligation to restore Willamette River habitat damaged by 75 years of mining at Ross Island.

“We were blindsided,” says Bob Sallinger, director of conservation at the Audubon Society of Portland, which pushed for a reclamation plan 20 years ago.

In 2002, Ross Island finalized an agreement with the Oregon Department of State Lands, which regulates river bottoms. That plan followed a blistering Oregonian investigation of Ross Island’s mishandling of contaminated soil the company used to begin refilling the river bottom, which had been mined to a depth of 125 feet.

In a 2001 interview with WW about why his company was getting into the newspaper business, Pamplin groused about the daily’s coverage. “They weren’t balanced,” he said as his company launched the Tribune to compete with The O.

The company told the state it would reclaim the river bottom with clean fill and restore upland habitat.

Two decades later, the work isn’t close to being finished.

“Our expectation was they would complete the reclamation by 2013, but that wasn’t put into permits so couldn’t be enforced,” Sallinger says.

The DSL has now placed an enforceable end date on the company: 2035.

Lien on Me

Over the past four years, various suppliers and one lender have won judgments against certain R.B. Pamplin Corp. subsidiaries. Labor groups successfully sued Ross Island Sand & Gravel dozens of times in federal court for failing to make contractually required payments to union benefit and retirement trusts (both are separate from the R.B. Pamplin Corp. pension fund for nonunion workers).

Nearly all the lawsuits WW reviewed were decided against Pamplin Corp. companies.

In addition to the raft of lawsuits against Ross Island Sand & Gravel, other Pamplin Corp. subsidiaries have struggled to make payments. For instance, Columbia Empire Farms got sued in 2020 for failure to pay Federal Express ($14,500) and a trucking company, Dominion Freight Lines ($41,450).

Long before RISG closed its Portland concrete operations, the company regularly ranked among Multnomah County’s largest property tax nonpayers, running balances in the low to mid-six figures. County records show the company currently owes $440,000.

Multnomah County charges 16% interest on property tax delinquencies. RISG effectively borrowed from the county at that rate, an expensive form of financing.

In 2019, Robert Pamplin briefly failed to pay his quarterly personal income taxes to the Oregon Department of Revenue. The agency filed a lien against him for $138,000 on Sept. 27. He paid it off less than a month later.

The Internal Revenue Service and Oregon Department of Revenue require employers to withhold income taxes from workers’ paychecks and send that money to taxing authorities.

Experts say failure to pay is a sure sign of financial distress.

“You don’t want to screw with the IRS on withholding of employee tax payments,” says Terry Deneen, a fellow at the Pension Rights Center. “It’s not your money; it’s the IRS’s money and the employees’ money.”

In 2020, the IRS filed a total of just over $2 million in tax liens against R.B. Pamplin Corp.’s news businesses; it filed another $500,000 in liens against Ross Island and affiliates, and a $325,000 lien against Columbia Empire Farms.

The companies have now paid off all but $900,000 of those liens.