As backlash grows against the city toughening its rules for unreinforced masonry buildings, a rumble of rumors can be heard—most of them from disgruntled property owners who think the safety requirements are a conspiracy. WW examined four of those claims.

Other places in Portland besides unreinforced masonry buildings will be dangerous in the event of an earthquake.

True but misleading.

According to some URM owners, City Hall should have higher priorities than making them upgrade their brick buildings. What about buildings in the liquefaction zone—the area mostly near rivers where the soil could become soft during the Big One? What about the fuel tanks in Linnton? What about the bridges?

It's true only one bridge in the city is up to seismic standards: the new Sellwood Bridge. (Westiders hoping to evacuate via bike over the Tilikum Bridge are out of luck: TriMet did not build the approaches to the car-free bridge to withstand liquefaction.)

Yes, the fuel tanks are a problem. Yes, in the Big One, soil around rivers may become so soft as to topple buildings not fastened to the bedrock.

But none of that makes URMs any less dangerous. In fact, URM buildings can collapse even without an earthquake strong enough to cause liquefaction, say the city's engineers.

"If we could make a list of the safety issues we're going to deal with in natural disasters, we're going to pick one and work on it and then work on the next one," says Courtney Patterson, interim director of the Portland Bureau of Emergency Management. "And URMs have taken the bandwidth for five years."

The city is requiring the upgrades because the mayor got campaign contributions from developers who could benefit from stricter seismic requirements.

Unlikely.

In the past six months, Mayor Ted Wheeler has received contributions from multiple real estate developers, including Jim Mark ($5,000), Vanessa Sturgeon ($3,000) and Greg Goodman's Downtown Development Group ($2,325). All of these are deep-pocketed investors who, a number of critics allege, have an incentive to push for tighter seismic rules because, the argument goes, URMs would drop in value if the rules are in place, thus creating a buying opportunity.

In reality, developers donate to politicians for a variety of reasons, and Wheeler has actually watered down the recommended proposals since taking office. He's been an agent of compromise on this issue, not the tip of the spear.

And the idea has been dismissed out of hand by two of the least developer-friendly members of the council, Commissioners Jo Ann Hardesty and Chloe Eudaly.

"There is really not a hidden agenda here," Eudaly told the council Feb. 27. "I've really been disappointed by the misinformation by opponents."

"That's so far from the truth," says Goodman, who supports finding tax breaks or other public support for URM building owners. Goodman also says his donation to Wheeler is because they share similar politics. "He's doing a reasonable job," he adds.

The city's list of URMs is inaccurate.

Mostly false.

In the 1990s, the city conducted a visual scan of buildings to find URMs. From that list, city engineers in 2014 reviewed photos, Google map images, and property records to create a database of 1,650 buildings.

Since then, the Bureau of Development Services has put in place an appeals process for removing buildings from the list. Of the 45 buildings whose owners have appealed, 20 have been removed. (A handful, like Crystal Ballroom, were removed because they had completed upgrades.)

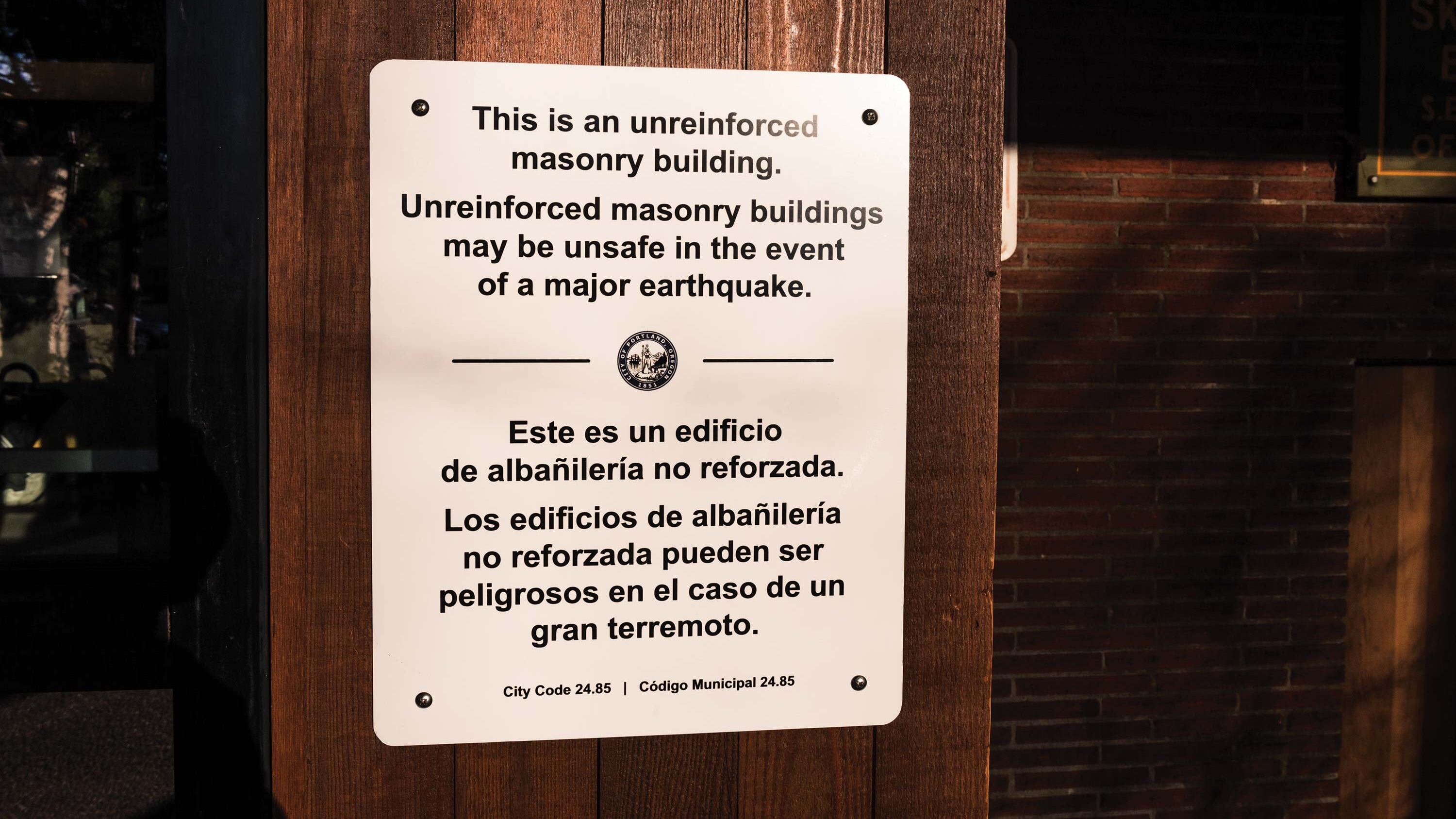

The accuracy of the list is also part of a federal lawsuit filed by lawyer John DiLorenzo on behalf of owners to permanently halt the placarding requirement. The lawsuit argues the warnings violate the free speech rights of the owners.

The proposed placards would be misleading, because they would be required even on buildings that have done partial seismic upgrades.

Not necessarily.

The city says it has told business owners they may add information to the required placard—including, for example, public schools telling parents that only the gym of a school is a URM.

The concern, of course, is that retail businesses and rental properties operating in URMs might lose customers confronted with a sign warning a building could fall down in a quake.

The counterargument is that people should get to make an informed choice.

To an informed observer, the fear is already there.

"I actually get a little bit nervous coming to Portland," testified Oregon State University geologist Chris Goldfinger, the pre-eminent scholar on the Cascadia subduction zone, in a hearing before the City Council on May 9. "I look around and see a lot of URM buildings. When I head down I-5 toward Corvallis, I can relax a little bit."

Read WW's cover story on the earthquake-preparation backlash.