For at least 15 years, Randy Rapaport has been an idiosyncratic developer with a nose for Southeast Portland trends. But since February 2018, he's been racking up city fines.

That's because the former auto body shop he owned in the Montavilla neighborhood is being used as an artists collective—he converted it into artist studios. City officials have fined him more than $13,000 for, among other things, improperly converting a commercial space to a new use.

To express his displeasure with the fines, Rapaport last week lobbed a bomb of an email at City Hall, pledging to evict everybody and mocking the city's commitment to artistic, ethnic and racial diversity.

"I wanted you to know that I'm planning on kicking everyone out of the building—the artists, a purple-haired vegan sticker maker and a blond dude who photographs beautiful people using a digital camera," he emailed the Bureau of Development Services and a city commissioner on July 31. "I will also be removing the small cart pod—which has been there for a very long time—serving the African American and stoner community with Jamaican food, the Mexican community with a taco cart, a Thai cart serving the Thai community, and a Hawaiian cart mostly serving skinny white stoner dudes.

"I will phone your office myself as soon as everyone is out so you may inspect a deserted, soulless place—devoid of life and creativity," he added.

Rapaport says his fury is in response to a sea change in the city. A decade ago, he says, his plan for a temporary artist collective—allowing artists to bivouac there with his permission while he prepared to develop the site as affordable apartments—would have gone off without a hitch. "This could have happened because nobody would have turned you in," Rapaport says.

The number of tenants who could face eviction is small: Five people live in the building and 10 rent artist studios. Rapaport has already made hundreds of thousands of dollars off the property—so he can hardly complain the city is robbing him.

So what's he so upset about?

He's furious the city doesn't think his artist community—and others like it—should be allowed wiggle room around the rules to protect creative spaces that are vanishing amid new development. "I want this to be a case study for city policy to adopt to have exceptions for limited periods of time when there's something that's good for the culture," he says.

But his complaint goes deeper—it taps into the resentments of a generation of Portlanders who once were the city's coolest cats, and now feel its free spirit has been lost to real estate, while its residents haggle over the rules and who gets priority.

His crusade has attracted old-school luminaries of Portland's arts scene.

"I'm with you," emailed Thomas Lauderdale, bandleader of Pink Martini, in response to another Rapaport email to the city about the fines. "This city is barely functioning. When journalists ask me about Portland, I don't answer the question because I can't think of a single thing that is happening in this city that I think is amazing. It's just a series of bumbled, missed opportunities. We've joined the rest of the country, I'm afraid."

Lauderdale, who has previously considered running for mayor, also complained about the closing of a downtown MAX station, blaming "no real leadership from the City Council or from organizations like Travel Portland and Portland Business Alliance, not to mention 'Prosper' Portland."

WW asked Lauderdale to elaborate. "I don't know that I really want to add to the poop-lobbing," he replied via email. "The city is in so much trouble as it is, and unless one has something inspiring to say, I don't think it's actually constructive to fan the fires."

What exactly has been lost is hard to define: Rapaport described a disappointment with City Hall that only adds to the cost of living with increasing red tape. Rising home values made him money but pushed artists out of the city.

For city officials, the issue is much simpler: They told Rapaport he isn't allowed to let tenants live there without making required upgrades.

The city's Bureau of Development Services "has evaluated all information and worked with Mr. Rapaport to the best of our ability to provide a clear path to legalize the current operation and correct the cited violations," says bureau spokeswoman Emily Volpert.

Rapaport, who grew up in Miami, was a school psychologist for six years before turning into a developer. He developed the Belmont Street Lofts, the old Stumptown Coffee location in Sunnyside, and the Clinton Condominiums just off Southeast Division Street, where he still has a home.

Originally, Rapaport planned to develop the former garage at 518 SE 76th Ave. into affordable housing within six months. (He never formally applied to the Portland Housing Bureau for funds, the bureau says.) But the arts collective's life has been extended another two years because Rapaport's project never took off.

In June, he sold to a nearby property owner, but says he would help keep the artist spaces until the end of the year, if the city stopped fining the building.

In decades past, artists would have been allowed to take over the spot until development happened, Rapaport contends. The city wouldn't have noticed, because no one would have complained.

"It's complaint-driven," he says. "That's why they even knew. If they didn't hate us—the minority—we'd be fine."

But neighbors did turn him in—as early as August 2017. Rapaport's property was reported for hosting an illegal Airbnb, city records show, which Rapaport readily admits. But he says it was only once. "We had a gay Parisian chef dude who makes chocolates," says Rapaport. "It was great. He spent one night there."

Once inspectors visited to investigate the Airbnb complaint, the city says they discovered other problems. Along with citations for letting people live on a commercial property, Rapaport was cited by the city for parking on unpaved portions of the property, for having a wall mural without a permit, and for converting the auto body shop into an artist studio without obtaining the required change to occupancy.

An architect hired by Rapaport says the city erred in several of its more technical citations.

"Things have gotten adversarial," says architect Jason W. Kentta. "Relatively inexperienced people [at the Bureau of Development Services] are looking to pick fights."

The city stands by its fines. "BDS never agreed with Mr. Rapaport's position," says Volpert.

Meanwhile, Rapaport has made money. He bought the property for $1.5 million in March 2017 and sold it for $2.1 million in June. He says adjacent property owners were willing to pay extra for a larger parcel to redevelop.

He estimates he made $300,000 in two and a half years. While the rent from the artists has mostly covered his costs for the past six months, it took a while to come together and he's invested in projects and events at the Pegasus Project.

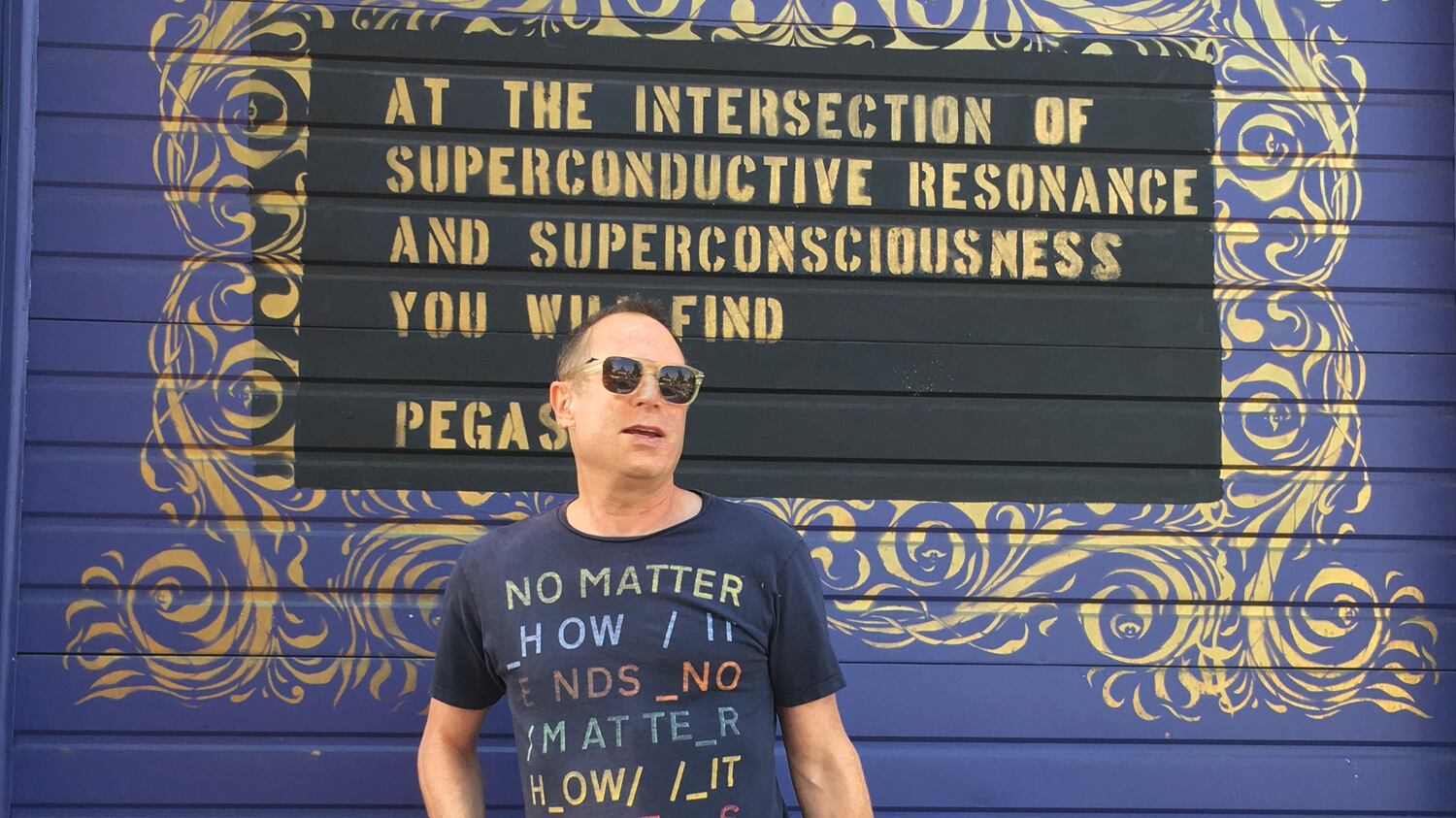

Last week, Rapaport offered a tour of the imperiled space, called the Pegasus Project. (Afterward, he would fly to Las Vegas—where he was to play high-limit roulette to test his extrasensory perception. "It's a controlled-environment art project. Think of it as time-based art with Veuve Clicquot.")

Inside the small purple building at the corner of Southeast Stark Street and 76th Avenue, Pegasus art director Joshua Wallace, who got his start with graffiti under the tag Sasquatch 23, showed off his "hash tag"—a drawing, or "tag," using paint made from hash oil.

Pegasus Project hosts a weekly open-mic night and yoga classes. Classes for kids are planned in the future. A sticker maker has rented one of the studios, a photographer another.

"The neighborhood has been needing a space to be creative," Wallace says, citing an outpouring of interest at a recent street fair. "I wanted people to come here and feel accepted and inspired without any money or capitalistic venture, especially in a time of such political and social disarray. I wanted to create a spot that was safe, welcoming and just really helped people heal. At a time when the world is getting bigger and scarier, you can just come here and be yourself."