On a warm Sunday afternoon, Gateway Discovery Park looks like a postcard.

It’s easy to miss the park while driving along Northeast Halsey Street, the Hazelwood neighborhood version of Main Street, lined with a True Value hardware store, the former King’s Omelets family restaurant and a nearly finished low-income apartment building, christened the Nick Fish.

Behind that building sits the park, a $10.2 million oasis the city built in 2018 to give residents of Portland’s easternmost neighborhoods the kind of communal space they’d long been denied.

Children climb on a hill of green artificial turf, bang out notes on a metal xylophone and pedal Huffy bikes along paths painted blue. Moms spread a plastic Spider-Man tablecloth across picnic tables and inflate red birthday balloons. Heshers split a six-pack of Hamm’s next to the concrete skate bowl.

But all is not well at Gateway Discovery Park.

Adalia lives across the street from the park. It’s a place her family avoids after dusk. That’s when they tend to hear gunshots.

On a recent night, she says, dozens of people shot at each other. Even during the day, Adalia, who asked not to use her real name, can’t sit in the park without feeling edgy.

“You never know what’s going to happen, but we can’t just stay at home all the time,” Adalia says in Spanish. “Some weeks there are shootings every other day and sometimes just every weekend. We always hear sirens outside our home.”

Last August, Gateway Discovery Park was the scene of a mass shooting. A few minutes after sunset on Aug. 27, someone shot four people. One died: 16-year-old Jaelin James Scott. His father, Cash Carter, says the boy exchanged texts with his grandmother minutes before he died.

“He was outside and then she texted him and was like, ‘Can you go get me a soda from the store?’” Carter says. “And the last text she got from him was, ‘I’ll get you a soda after I come back from the park.’”

For the past year, gunfire has torn through this city at a rate Portland hasn’t seen in at least a quarter century. The number of shootings citywide more than doubled in a year—from 393 in 2019 to 890 in 2020.

The brunt of the violence is borne by Black Portlanders, like Jaelin Scott.

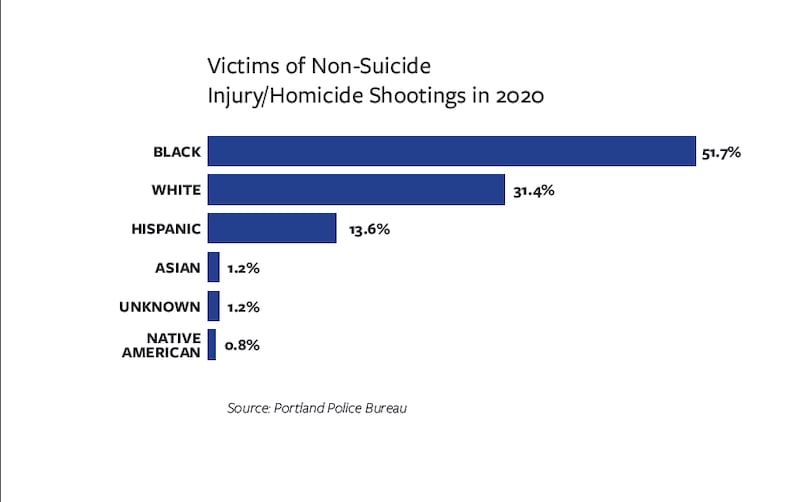

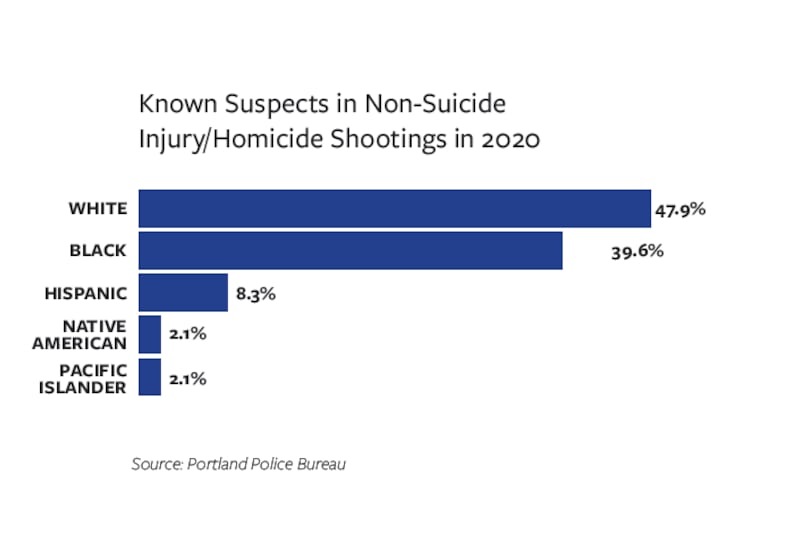

WW has exclusively obtained Portland Police Bureau records that show, for the first time, the racial demographics of all known suspects and victims of non-suicide shootings in 2020.

Black people made up 39.6% of suspects and 51.7% of the victims. That means Black Portlanders were injured and killed at a rate eight times higher than their share of the population.

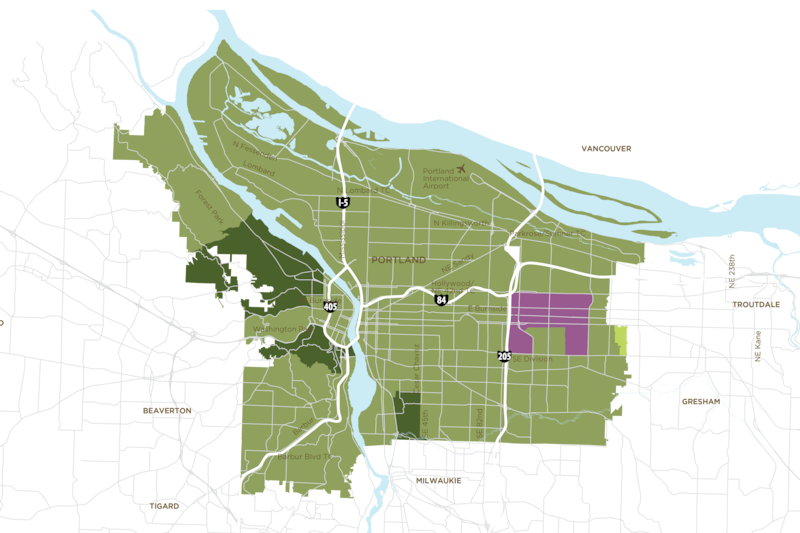

No place in Portland has endured gun violence like Hazelwood, the neighborhood with the fourth-highest number of Black residents in the city.

For the past three calendar years, it is the neighborhood where bullets fly more often than anywhere else in Portland. Last year, 1 in 13 of the city’s shootings happened here. Yet only 1 in 25 Portlanders call Hazelwood home.

Hazelwood’s 4.1 square miles stretch from 102nd Avenue to 148th. In between stand enormous fir and hazelwood trees, vast car lots and pastel-painted former fast-food franchises now serving food from around the globe. Tightly packed wooden apartment buildings sit next to a nearly vacant mall, a hospital campus and the only Portland outpost of Pig ‘N Pancake.

And it is a place where, as the COVID pandemic subsides, many residents still feel the need to stay inside.

In the past month, we sat down for conversations with people in or near Hazelwood who have endured and survived the violence firsthand.

A Black mom says she can’t find a safe or supportive environment for her son. A food cart owner says he wants to move his truck out of the area. A longtime resident moved to Beaverton a year ago to keep his family safe. And a county commissioner says she’s worried every time her teenage daughter leaves the house to go to the park across the street.

City Hall is now locked in an intense debate over whether the 2020 removal of a police unit focused on gun violence helped cause the rise in deaths of Black Portlanders. The people we spoke to in Hazelwood were keenly aware of a reduced police presence. Some said police could help reduce lawlessness. But few of them felt that was the fundamental problem—or the sole solution.

Instead, they described a disproportionate number of single-parent homes and lack of positive Black male influences for young boys. They talked of teenagers with little to no school or mentorship being manipulated and raised by seasoned gang members. And they pointed to the grief and fear of watching friends and relatives die that never gets processed—leading to gun violence as a last resort.

“While they’re writing laws, we’re writing obituaries,” says Lionel Irving, founder of nonprofit PDX Love Over Hate and a gang veteran who now counsels young men not to pull the trigger. “Something has got to be done. If we wait, we’re going to keep getting kids in the grave.”

Here is how eight people have survived in Hazelwood. And here is how they think the shootings could stop.

Cash Carter

The night Cash Carter’s son died, he drove from hospital to hospital trying to find him. For nearly three hours, Carter didn’t know whether his son, Jaelin James Scott, had survived the gunshots at Gateway Discovery Park.

“At one point in time at [Legacy] Emanuel, before we left, I could swear I heard him say, ‘Dad,’” Carter says. “I swear. I know his voice.”

Scott, 16, died from his wounds.

In the months before the Aug. 27 shooting, Carter, 40, had been running for Portland mayor. His platform included reform of the juvenile justice system, which Scott had entered. Carter also wanted to set an example for his son by seeking office.

In May, Carter finished ninth among a 19-candidate field. But Scott slipped further into gang involvement.

“He got messed up in the wrong crowd. By the time that I’m showing him positive things, he’s already in it,” Carter says. “I’m doing something positive, running for mayor, you’re winning—and then boom. You’re losing. Then you’re at the lowest of the lows.”

Carter sports a red, black and white sweatsuit that has roses on it, and wears a pair of dark sunglasses. He’s proud of how close he was to his son; it gives him comfort that Scott viewed him as his best friend.

Scott struggled to stay out of trouble even with mentors and probation officers who Carter says could’ve held his son more accountable when he fell out of line. But Carter remembers Scott as a boy with enormous potential: effortlessly funny, charismatic, and able to offer advice beyond his 16 years.

“Everybody liked him. He could light up a room. He was a good big brother, a loyal friend,” Carter says. “He was a natural at music ever since he was a little kid. I wrote this hook for him when he was 4 or 5, and he just killed it.”

Scott is survived by his younger brother, who is just 8 years old. “He handles it right now better than I do,” says Carter, who is attending weekly grief counseling sessions.

Carter says it wasn’t just gangs that killed his son. He believes social media platforms fueled violence on the streets of Hazelwood. Carter saw Scott caught up in feuds between young men that started with insults delivered on Snapchat.

But Carter thinks that social media could become part of the solution: Snapchat advertisements could help spread the word to this younger generation with messages that Carter suggests could say something like, “Think before you Snap,” or “Don’t end up like this person.”

“They’re on their phones all the time,” he says, “so put it on their phones.”

Isaiah Bostic and Armando Fernandez

Armando Fernandez thought the popping sounds at Food Cart Heaven were fireworks.

It was around the Fourth of July, and the co-owner of Mando’s was dishing out his signature burgers—each named after a neighborhood, like Alameda, Laurelhurst and the Pearl District—out of a blindingly red converted mail truck. “We looked outside and everyone was down ducking on the ground,” Fernandez recalls.

The noise was gunshots. One of the bullets shattered the rear window of Isaiah Bostic’s car. Most days, that’s where his daughter and niece sit and play while he’s dipping corn dogs at his cart, Batter on Deck.

“One day they both said they didn’t want to come,” Bostic says. “Any other day, the girls were sitting in the car.”

Gun violence doesn’t stop at a neighborhood line. Food Cart Heaven sits nine blocks east of Hazelwood on Northeast Glisan Street, in a neighborhood called Glenfair. You can see Gresham from Fernandez’s truck.

The cart pod is a tightly packed ring of rainbow-painted food wagons circling green picnic tables under huge Douglas firs. The carts serve tacos, fish on a stick, and a whole roasted chicken for $14. Bostic specializes in whole potatoes, spiral cut and fried, also on a stick.

The parking lot has been the scene of two shootings in a year, Fernandez says. The most recent was last month, when two cars pulled up in front of the adjacent, pale green office building, where tenants include a Farmers Insurance office, a dog groomer and an OnlyFans agent. Parked outside the office, the drivers began firing at each other.

Fernandez is considering moving locations after three years in the pod.

“There’s a lot of gang activity going on, and I think that has to do with a lot of it, and then drugs, of course,” Fernandez says. “Some new customers, you can tell they’re a little intimidated and scared out here.”

Bostic, who opened Batter on Deck in May of last year, has already moved his family out of Hazelwood. He commutes to the cart from Beaverton each day it’s open.

“I don’t live over here anymore,” Bostic says. “If I have to do that to keep my kids safe, it’s what I have to do.”

Bostic thinks that one thing young Black men on the streets really need are jobs. So he recently hired 24-year-old Laron Barrow.

“Jobs can definitely change a person—I know it changed me. A person that’s broke don’t have nothing to live for. A person that’s got something to do and money, he’s not going to jeopardize that,” Bostic says. “If [Barrow] wasn’t here, I know what kind of person he would be and what he would be doing and who he would be hanging with.”

Laron Barrow

Barrow, 24, says one of his favorite parts of living in Hazelwood is the number of Black people who also live there. Yet for much of the past year, he avoided leaving home because of the spike in shootings.

On New Year’s Eve, a friend persuaded him to make an exception and go to a house party.

“My homie begged me to go out. I had just got there and had been there for 30 minutes when a girl fell on me when she got shot,” Barrow says.

The woman survived. Barrow says that’s the new normal in Hazelwood.

“You kind of get used to it after a while,” he says. “You’re traumatized by it, but it’s a normal thing.”

As Barrow talks, he shakes the short dreads from the front of his face, which features sharp cheek and jawbones. He’s the single father of a 7-year-old son who is the reason Barrow stays indoors when he isn’t dipping corn dogs at Batter on Deck. He wants his son to have a father—unlike him.

“They took our fathers away, so we don’t have people to mold us into a woman or a man to know what the hell is coming up in life,” Barrow says. “They’re taking away our fathers, they’re taking away our mothers and making us figure it out on our own.”

For parents like Barrow who have to work and raise children, the closure of schools during COVID-19 was a calamity. Those children, Barrow says, were left to fend for themselves—or to be raised by other children.

“They’ve got their nephews watching their kids who are 13 or 14, and they have friends over who are gang banging, so what do you think their nephew is going to do?” Barrow says. “We’re losing that parent figure in our homes.”

Barrow’s main priority each day is to make it home unharmed so his son can grow up with a father.

“I’m trying to make it home,” he says. “That’s the biggest thing for me right now, to make it home. It’s fucked up, messed up, but I guess that’s just what Portland is now.”

Kenneth Combs

Combs, 39, was shopping in a Walmart on Southeast 82nd Avenue last month when a fight broke out. The woman he was talking to heard the discord. She dropped her shopping basket and walked out of the store.

That reaction, he says, is what a year of shootings did. “It makes you more cautious. You have to look around,” he says. “There’s so much fear here that it’s pushing people away from wanting to do things.”

It is a bleak irony of a shooting wave amid a pandemic that the places where people can still gather—outdoor spaces, like parks and food cart pods—are the places where people can get caught in a crossfire. Combs understands this: He too runs a food cart just outside Hazelwood, a barbecue ribs and catfish joint named Verajames, after his grandparents.

He doesn’t feel safe bringing his two children to work anymore. Last summer, shots sounded from the strip club a block west on Southeast Division Street. “We just all kind of hid behind the cart,” he recalls. “You knew what happened.”

Combs was born and raised in Portland; his grandfather’s name adorns James Lee Combs Field at the Riverside Little League. He says something in the neighborhood has changed.

“Laws have been really loose around here,” he says. “A lot of people went out and got a car and got a gun. As the crime goes up, you want to protect yourself.”

He worked for two years as a pawnbroker before starting Verajames. Now he wonders: Who’s selling the guns to teenagers? Who’s talking to them? Why aren’t elected officials in the streets of Hazelwood, demanding something better than this?

“It’s not the police’s job to raise your kids,” he says. “There’s got to be a change and it’s got to be soon. We lose time, we’re losing a kid.”

Jessica Vega Pederson

Elected officials live in Hazelwood, too. Oregon’s newest state representative, Andrea Valderrama (D-East Portland), calls the neighborhood home. U.S. Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) has a home one block outside Hazelwood, in Mill Park.

Last August, Multnomah County Commissioner Jessica Vega Pederson was playing Minecraft in the family room with her husband and daughter when she saw a man pull out his gun and fire shots toward the park across the street.

She remembers the focus in the man’s eyes. He was shooting as if he had no awareness of his surroundings.

Now Vega Pederson fears for her 13-year-old daughter each time she leaves the house. “Our only outlet have been walking or biking around the neighborhood,” Vega Pederson says. “That’s something my daughter does on a regular basis. It’s something I think about.”

This month, Vega Pederson tacked an amendment onto the county budget: $300,000 for life coaching and grief support groups for teenagers who are considered high risk to pull the trigger.

Ashley Slaughter

In May, Slaughter went on Facebook in search of a big brother figure for her 16-year-old son, Jawuan. She had received a call from his track coach at David Douglas High School about his dwindling motivation.

Jawuan has been missing a positive father figure in his life ever since Slaughter’s fiancé was killed in a shooting six years ago. She feels that Jawuan’s biological father isn’t a positive role model.

“Being a Black woman and raising my son by myself—it’s been tough,” says Slaughter, 37. “I feel bad for him when he misses that dad part of his life, when he tells me he feels lonely and depressed because he doesn’t have a guy around to talk to, and I don’t know what to do on that part and that’s when I have to reach out.”

Her son loves to play sports: swimming, golf, gymnastics and others. He also volunteers by helping out his grandmother’s nonprofit, PDX People of Color Outdoors, but Slaughter says he also spends a lot of time alone at home while she’s at work as a deputy CFO for a technology academy.

Juwuan has been even more isolated since they moved to the Hazelwood neighborhood from North Portland.

“In New Columbia, it’s safe for the kids to walk around by themselves. Now I don’t like our area,” Slaughter says. “We hear firing all the time, and I don’t feel comfortable with him walking around—and he feels restricted because of that.”

Slaughter, who wears blue acrylic nails and dons a colorful cardigan sweater on an unseasonably chilly June afternoon, loves the outdoors, especially canoeing. As a year alone stretches into two, and one pandemic bleeds into another, she’s already considering moving out of the Hazelwood neighborhood, after just six months here.

She wishes the city would provide programs for single-parent families that were culturally-specific and would allow teenagers of color to associate with supervision, instead of just wandering around.

“He’s pretty used to being around a lot of people of color and a lot of other kids,” she says. “I feel like it’s something that a lot of boys need. I shouldn’t have to jump through hoops and work so hard to get information on how to help your kid feel supported.”

Jawuan has excelled at everything, she says. But this year feels like a turning point.

“I can only do so much as his mom. I am always going to be there, but I can’t relate to certain things that he may be feeling,” Slaughter says. “I know when they don’t have connections, sometimes they can look for that in the streets. I don’t want him to, and I don’t think he will. But no one ever thinks that their child will.”

Lionel Irving

Irving expects a deadly summer.

“Last year and last summer you can’t even compare to what’s going on right now. No one has witnessed this amount of shooters and young men dying,” he says. “We watch the whole generation come down. And there’s anger from not knowing who did it and the lack of the support from the community.”

Portland hasn’t seen shooting numbers like this since the 1990s. Except this time it’s worse, says Irving.

He would know. Three years ago, he finished a prison sentence of 14 years and eight months for crimes committed while a Portland gang member. His job now? Counseling young men, kids not so different from himself, trying to get them to forswear violence.

“I got lucky—not everyone gets a second chance like I did,” he says. “But there are so many men in prison who are just like me, if not better, who would have a lot of knowledge to offer the community.”

Irving is a confident, powerful presence, with a sharp intelligence. He only purchases clothing made by Black people or other people of color. Today, as he visits a food cart pod, that’s a dark yellow sweatshirt from Black Mannequin and a matching black and yellow Blazers cap.

He lives in the Piedmont neighborhood. But he spends many of his days in Hazelwood. That’s where the kids are shooting each other, he says.

“We have a pandemic in our community,” he says. “All the men are in prison. The mother is trying her hardest to provide. The streets is going to be his father. It’s creating a cycle.”

Irving thinks local leaders are making a mistake by labeling Portland’s shootings as mainly gang violence. Some of it is, he says. Some isn’t. And the legacy of gang affiliation is too closely interwoven into neighborhoods like Hazelwood to easily categorize it.

“It’s intercommunity violence—it’s not all gang violence,” Irving says. “Of course, it’s also gang violence but that’s a loaded word. It’s really a stereotype. They’ve been saying that since I was a child. They don’t have to be gang members retaliating. That’s just a concept people have. Some of these guys are their older brothers or their cousins.”

He thinks that incarcerating Black men—including by adding additional time to sentences for people believed to be in gangs—will only leave a larger vacuum for teenagers.

“You think about how malleable a 19-year-old mind is,” Irving says. “So are we going to let somebody else mold that mind? Continue to put that poison in there? Or are we going to interject some positive fruitful thoughts that can grow?”

He’s thinking of one 19-year-old in particular. Irving encountered that young man a few weeks ago, in the aftermath of a shooting. The Black teenager was visibly distressed. His friend had just been killed.

Irving hugged him. He told him: The friend left behind two young sons, so now it’s your job to fill the hole that was just made in their lives.

“Nonsense,” the young man said.

“Is it nonsense to raise your partner’s son so he don’t get put in a casket?” Irving replied. “That’s nonsense to you?”

The young man looked at Irving. “Man, that’s not nonsense, but I can’t even wrap my mind around that.”

The admission moved Irving. It was so honest: The violence in Portland had simply overwhelmed the young man’s ability to understand it. The deaths were too many. The hole is too big.

“That was such a powerful statement,” Irving says. “I know that in my heart, I believe, he’s going to be one of those guys that’s going to be there for them young men.”

Reporting for East Portland

This story is the result of a yearlong partnership with Report for America, a national service that places journalists in newsrooms around the country. For the past year, Latisha Jensen has covered East Portland and examined the racial disparities that underlie much of daily life in this city. Perhaps no disparity is as stark as the gun violence that fills Hazelwood residents with daily worry.

To find out how you can contribute to more WW coverage like this, visit wweek.com/fund.