During Portland’s record-breaking heat wave, the pavement at the intersection of Southeast Woodstock Boulevard and 92nd Avenue registered 180 degrees. That’s hot enough to slow cook a pot roast.

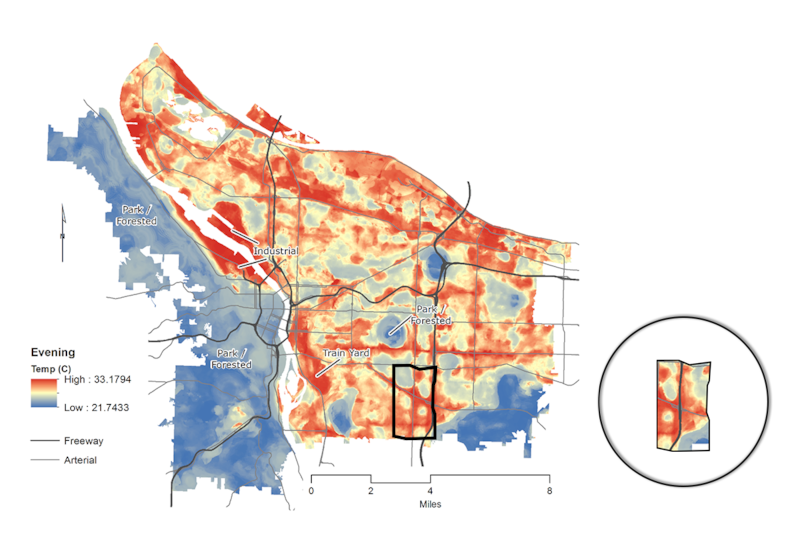

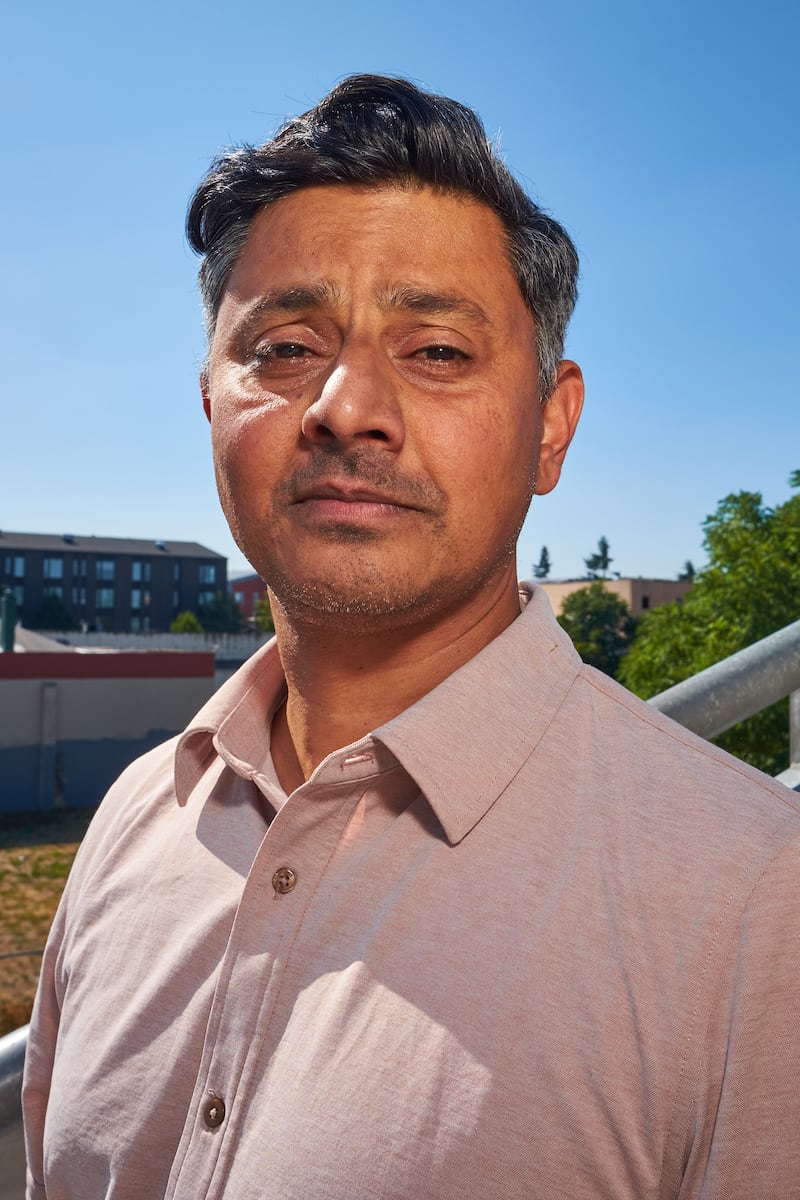

On June 28, Dr. Vivek Shandas drove his Toyota Prius across the city. He and his 11-year-old son, Suhail, used a thermal camera to measure the temperature in neighborhoods from the Pearl District to Gresham.

No place was hotter than that intersection, next to a Planet Fitness in Lents Town Center.

At about 4 pm, the temperature in the air was 124 degrees. That was 9 degrees hotter than the city’s average, and 25 degrees higher than what Shandas measured in Northwest Portland.

And the sidewalk was superheated to 180 degrees. Walking on it barefoot would give you third-degree burns.

Shandas felt a blast of blistering air as soon as he opened the Prius door.

“The first thing I felt was my eyes were burning, like my sockets,” Shandas says. “My skin was on fire. It just feels like you’re melting.”

Shandas isn’t engaged in an eccentric hobby. A Portland State University professor who studies climate change and how to address its implications, he understands that certain neighborhoods have the ingredients for lethal heat that other neighborhoods do not. Principally: few trees and lots of concrete.

And, as Shandas points out, at this intersection, 10 miles east of downtown, the pavement runs three lanes wide. A large parking lot with dark asphalt borders the road. A cluster of tall, dark buildings blocks any breeze.

And looming over the scene is more asphalt: the eight lanes of the Interstate 205 overpass. The dry, brown grass looks like the high plains, broken only by a handful of spindly trees topped with little tufts of green.

When the “heat dome” descended on Portland two weeks ago, these elements turned neighborhoods like Lents and Foster-Powell into an oven.

Four ZIP codes east of 42nd Avenue, lined by major arterial roads or interstate highways, had four deaths apiece. That’s the second-highest number in the city, exceeded only by downtown. These four ZIP codes accounted for nearly a quarter of Portland’s heat deaths.

That comes as no surprise to Shandas: He’s been warning Portland about just how severe these hot areas of the city are for a decade.

“To see folks that have died? We had so much evidence to show this was a likely outcome,” Shandas says. “Without direct mitigation of these places that are often 15, 20 degrees hotter, we’re going to continue seeing people die.”

The 71 people killed by extreme heat in Multnomah County last month were arguably Portland’s first deaths from climate change. They were also victims of one of the largest natural disasters in civic history.

In three days, more people died in Multnomah County than were killed by COVID-19 in nine days at the height of the pandemic. The heat killed more people than the Vanport Flood (15 people), a 2014 landslide that wiped out Oso, Wash. (41 people), or the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens (57 people).

Portland’s heat deaths—54 of them officially confirmed as hyperthermia—haven’t had a similar impact on the public imagination. They were all but invisible. People died in their own homes, and county and state medical examiners declined to release the names or addresses of the deceased. The victims died anonymously, their circumstances a secret.

Yet make no mistake: They were victims of a natural disaster, and their deaths were hastened by where they lived, as surely as if they had stood in the eruption path of a volcano.

Shandas points out that the burden of climate change does not fall equally. Instead, it has killed people living without air conditioning, amid vast swaths of concrete, and with few trees to provide shade. We also know most of them were found alone, indicating that social isolation was a primary factor in their deaths.

And the next time the mercury rises, these neighborhoods will become death traps again.

“Now we’re seeing this East Portland perfect storm coming together,” Shandas says. “The way we’ve gone about building our city and the design of the roads, the buildings, the amount of green space—that combined with people who often don’t have easy ways to cool off, that comes together to increase the likelihood of deaths.”

Shandas predicted three years ago what Lents would feel like in an extreme heat wave.

In a 2018 study he co-authored at Portland State University, he warned that those with underlying health issues and low-income and homeless people were at greatest risk of having their safety compromised by these heat islands. And he pinpointed the places at greatest risk: neighborhoods in East Portland along arterial highways and I-205.

“Nonwhite, minimally educated, or poor English speakers, as well as those living in affordable housing, experience higher temperatures than their wealthy, white, educated, English-speaking counterparts,” the study concluded.

Why are Lents, Hazelwood and Parkrose so at the mercy of the thermometer? Three factors.

First, the materials they are built from. Dark buildings made of metal, brick and other dense materials absorb the heat. Cars whizzing along roads emit fumes and more heat. Highways and parking lots trap and absorb the sun’s heat and then re-emit it slowly over time.

Tom Armstong, a supervising planner for the city’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, says East Portland was developed after World War II under zoning that was “more auto oriented than inner Portland.”

The second factor of heat islands is breeze—or the lack of it.

At this Lents intersection, where the freeway stands above the four-lane road and five-story, mixed-use buildings are clustered together, the air stagnates.

“With the big buildings stuck together,” Shandas says, “there’s no way for the air to move around and create that cooling current that you tend to find in wealthier, leafier neighborhoods.”

Third, trees. They offer shade, drastically reducing temperatures under their cover, and greenery pulls up water from the ground and expels it into the air.

And the tree canopy disparity in Portland is stark. West of the Willamette River, 46% of the city has a tree canopy. East of the river, where 80% of Portlanders live, 20% is canopied.

“One of the defining natural features in East Portland were the Douglas fir groves,” Armstrong says. “And when development happened, that’s what came down. That urban form contributes a lot to the heat island we’re seeing out there.”

Shandas wrote his first report—warning about urban heat islands and whom they might hurt—in 2009. In a series of reports, he warned that through neglect, local governments were in essence creating neighborhoods that could kill.

He doesn’t feel local officials took it seriously enough. “Our climate system is intimate with our infrastructure systems,” Shandas says, “yet decision-making bodies don’t treat it as such.”

In 2017, Multnomah County released its five-year plan for reducing natural hazards. It acknowledged that extreme heat events were becoming more common—Portland had just seen 105-degree highs the previous summer—and that heat islands increased those risks.

It also defined heat islands as its top climate concern in its 2013 climate change preparation plan, and acknowledged the various factors that made certain areas more vulnerable.

But it offered no plan for how to tailor response efforts to different neighborhoods.

Instead, the county affirmed its support for the city’s long-term climate goals and pledged to keep discussing what to do.

The county has a standard operating procedure for severe weather, but it’s a general blueprint that’s modeled after federal and state forms, says Chris Voss, director of the county’s Emergency Management Department. It urges its nonprofit partners to check in with their elderly and disabled clients on hot days.

Multnomah County Chair Deborah Kafoury says the county has been following Shandas’ work and adding heat islands to its emergency response plans.

“In the short term, the county has prioritized the distribution of box fans to populations most likely to live without air conditioning in heat islands, and heat islands are a consideration in the location of cooling centers,” Kafoury tells WW in a statement. “But mitigating urban heat islands is a long-term task that requires collaboration.”

When the heat descended on Lents, it was overwhelming. A bakery owner, Michelle Vernier, said the outdoors felt like an oven. Michael Ta, who owns the Lents 1 Stop Market, closed early all three days during the heat wave—even with air conditioning, it was too hot to continue business.

“Oh, man, it felt like the air was burning,” Ta says. “I go down to California and Nevada a lot, and I like the heat, but not that hot.”

In the days before the heat wave arrived, county officials raced to identify places where people might die from overheating. They assembled a list of 67 apartment buildings and called big community development corporations with multiple buildings.

Staff cold-called the managers with an urgent message: Your residents are incredibly vulnerable. Please do what you can to keep them alive.

That didn’t always work. More than 12 residents of low-income housing told WW they never received a knock on the door.

“They did nothing to inform or prepare residents,” says Kelly Ralph, who lives in Peaceful Villa, a Home Forward complex for older tenants, most with disabilities, in the Richmond neighborhood—part of a ZIP code that saw four deaths. “They could have left the air-conditioned community room open as a cooling center. They could have offered bottles of water. They did absolutely nothing.”

Related: What’s it like to die from the heat?

While the limited data released by county and state officials about heat deaths doesn’t offer a full portrait of what killed people, it’s clear that living in a heat island wasn’t a death sentence. Thousands of Lents residents lived to tell tales about the sweatiest day of their lives.

Instead, the way Portland is designed left vulnerable people hoping their thin protections would be enough: insulation, a box fan, a window-mounted air conditioning unit. Those who died simply experienced a little bad luck.

The day before Eugene Anderson died, his AC broke.

Anderson lived in a trailer in the Flavel RV Park, in the same ZIP code as Portland’s hottest intersection—14 blocks away.

His long, white Allegro Bay trailer is sandwiched between two others, with no shade, fully exposed to the sun by noon. It’s a hunk of metal, plastic sheathing and rubber tires. Shandas takes one look at Anderson’s home and declares it a tinder box.

Anderson, a man of few words and little movement, walked like it hurt, neighbors said. He drove his RV to the grocery store, and then would carefully back it into its parking space on top of gravel and concrete.

Sandy Botkins, a resident whose trailer is parked about 200 feet from Anderson’s, says these trailers fail to keep out both heat and cold.

“This is like a tin can,” she says. “If I didn’t have an AC here, I could be melting even if it’s cool outside,” Botkins says. “We get sun morning, afternoon and evening. And these things get hot. You’ve only got skin, a quarter inch of air, and inside wall. And there’s no insulation in the ceiling.”

Related: The first heat deaths in Portland were nearly invisible. Here are two of the people killed.

Shandas imagines a solution tailored to the places suffering the most. The next time a heat wave strikes, he says, a squad of neighbors should be knocking on the doors of people like Anderson.

“I love these plans,” Shandas says, “because they could really resonate with Portland and its long history of neighborhoods.” He calls it a climate association.

Shandas is not shy about ideas for easing the burden of heat in East Portland. He thinks we should insert more gardens and trees into new developments. “There are design options where you can almost surgically insert green space,” he says.

City code does currently mandate trees for new developments. Those requirements were written in 2015. And the city also charges developers for cutting down trees: For every inch in diameter for trees over 20 inches wide, developers have to hand over $450. For a medium-sized, 20-inch-thick tree, that’s about $9,000.

But heavy industrial developments are exempt from the tree code, even though they border some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. And in 2016, the Portland City Council passed an exemption for affordable housing developers to forgo paying the tree-whacking fee.

“The rationale for that was, at what point does the housing not become affordable?” says Ken Ray, a spokesperson for the Bureau of Development Services, of the exemption crafted by late Commissioner Nick Fish. “At some point, the developers are going to say,

‘This doesn’t pencil.’”

But that means people living in low-income apartments don’t benefit from the same rules requiring shade. That outrages Shandas: “It creates a real inequity just in and of itself: Lower-income communities don’t get the privilege of green spaces.”

While trees are growing, Shandas has another simple fix to keep buildings cooler: Paint the rooftops white.

“Let’s bounce the heat back,” Shandas says. “We have bureaus that are able to institute different codes and standards to enable lighter-colored surfaces and surfaces that deflect the heat better.”

Portland City Hall will have a hard time saying it doesn’t have money to address such challenges—it’s sitting in the Portland Clean Energy Fund, a tax on the city’s biggest retailers that voters passed in 2018. So far, it has raised $115 million and distributed $8 million in grants. This fall, $64 million more will go out the door.

It’s not clear how much of that money will go to directly retrofit housing to be more climate resilient. Sam Baraso, the fund’s program manager, says 17 of the organizations receiving money are embarking on energy-efficiency projects and 11 are focusing on planting greenery or regenerative farming, or planning to do one of those two things.

Shandas says he’s encouraged PCEF to use most of its funds for creating climate-prepared buildings.

“I think it’s a direct means by which we safeguard from the heat. It’s like nothing else in the country—we can get ahead of the rising temperatures really quickly,” Shandas says. “It’s hard to say whether it’s enough. I generally think it’s never enough.”

City Commissioner Carmen Rubio agrees with Shandas: Portland isn’t moving fast enough to cool its hottest neighborhoods.

She says city leaders “must be aggressive, accelerated and nimble to disrupt climate change, and to decrease heat inequities in East Portland specifically. For me, this is not a ‘nice to have.’ It’s about saving lives.”