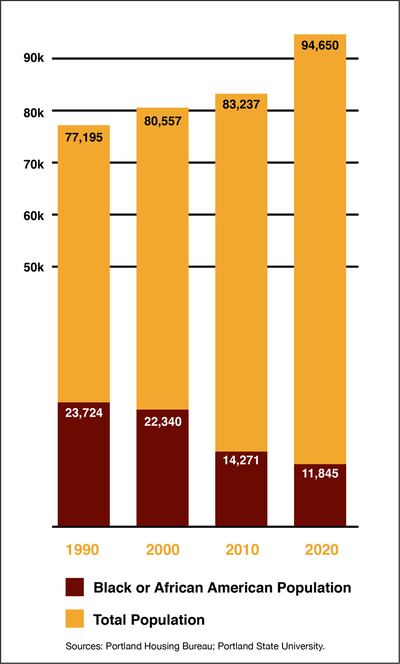

Newly released U.S. Census Bureau data shows Portland’s historically Black neighborhoods continued to see an exodus of Black residents, even as city officials have focused money and energy on reversing that decline.

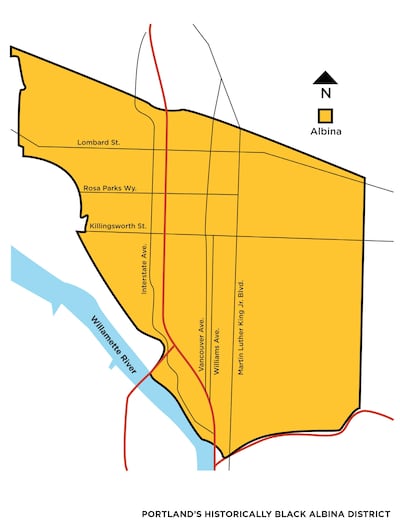

The demographic shift over four decades in the inner North and Northeast Portland neighborhoods of the Albina District is remarkable. In 1970, census data shows, 9 out of 10 Black Portlanders lived in those census tracts. Today, according to new calculations performed for WW by the Portland State University Population Research Center, just over 1 in 5 Black Portlanders live there.

Since 2015, the Portland Housing Bureau has been actively working to slow or reverse the decline, committing $80 million to a program called the North/Northeast Neighborhood Housing Strategy, which includes home repair loans, mortgage assistance and other investments aimed at keeping residents in Albina—or helping families pushed out by gentrification to return.

But that investment did not reverse the trend. In fact, the Black population of Albina shrunk again in the past decade—this time, by 2,500 people. (The previous decade, from 2000 to 2010, saw the same census tracts lose more than 8,000 Black residents.)

Shannon Callahan, director of the Housing Bureau, says she’s disappointed in the decline, which occurred even as Albina overall grew substantially—by 11,400 people. (Portland’s Black population as a percentage of total population remained unchanged from 2010 to 2020 at about 7.9%.)

“It’s unfortunate but not surprising that more Black households left,” Callahan says. “Gentrification is continuing, and pushing BIPOC families out of their homes.”

Charles Rynerson, PSU’s census guru, did note one positive finding in his analysis of the Albina numbers: Unlike in 2010, when every one of the area’s 25 census tracts lost Black population, four census tracts saw small double-digit gains, and a fifth added 335 Black residents.

Callahan says it’s too early to say for sure, but that gain may be the result of Housing Bureau developments, which have added 500 new affordable rental housing units in the area and have given preference to former residents pushed out by gentrification.

In addition to the Housing Bureau’s work, Prosper Portland, the city’s economic development agency, allocated another $32 million to preserve and bolster Black-owned businesses in the Interstate Urban Renewal Area, which includes Albina.

“The [census] numbers are a bit of a surprise to me,” says state Sen. Lew Frederick (D-Portland), who represents Albina in the Oregon Legislature. “I expected them to be worse—to show more folks had been chased out.”

Nkenge Harmon Johnson, CEO of the Urban League of Portland, says anybody who walks the neighborhood near her organization’s North Russell Street headquarters can see and feel the change wrought by developers who’ve gobbled up land along thoroughfares like North Williams Avenue.

Home flippers pepper homeowners with letters and text messages offering cash for homes. Hipster bars, restaurants and coffee joints contribute to jacked-up rents. It’s an onslaught inexorably pricing longtime residents out of their neighborhoods.

Harmon Johnson says the new census numbers show the city is “nibbling around the edges of gentrification” instead of attacking it head on. She wants a bigger commitment to subsidizing homeownership and bolstering financial capacity by helping young professionals with student debt. “Policymakers tend to be interested in the next flashy thing,” she says, “instead of workaday solutions that simply require more dollars.”