In 2010, I worked inside the Red Cross, in the cafeteria. Yes, Mom was a whole-ass cafeteria cook back in the day. Once I was on the news, ’cuz my soup was so good.

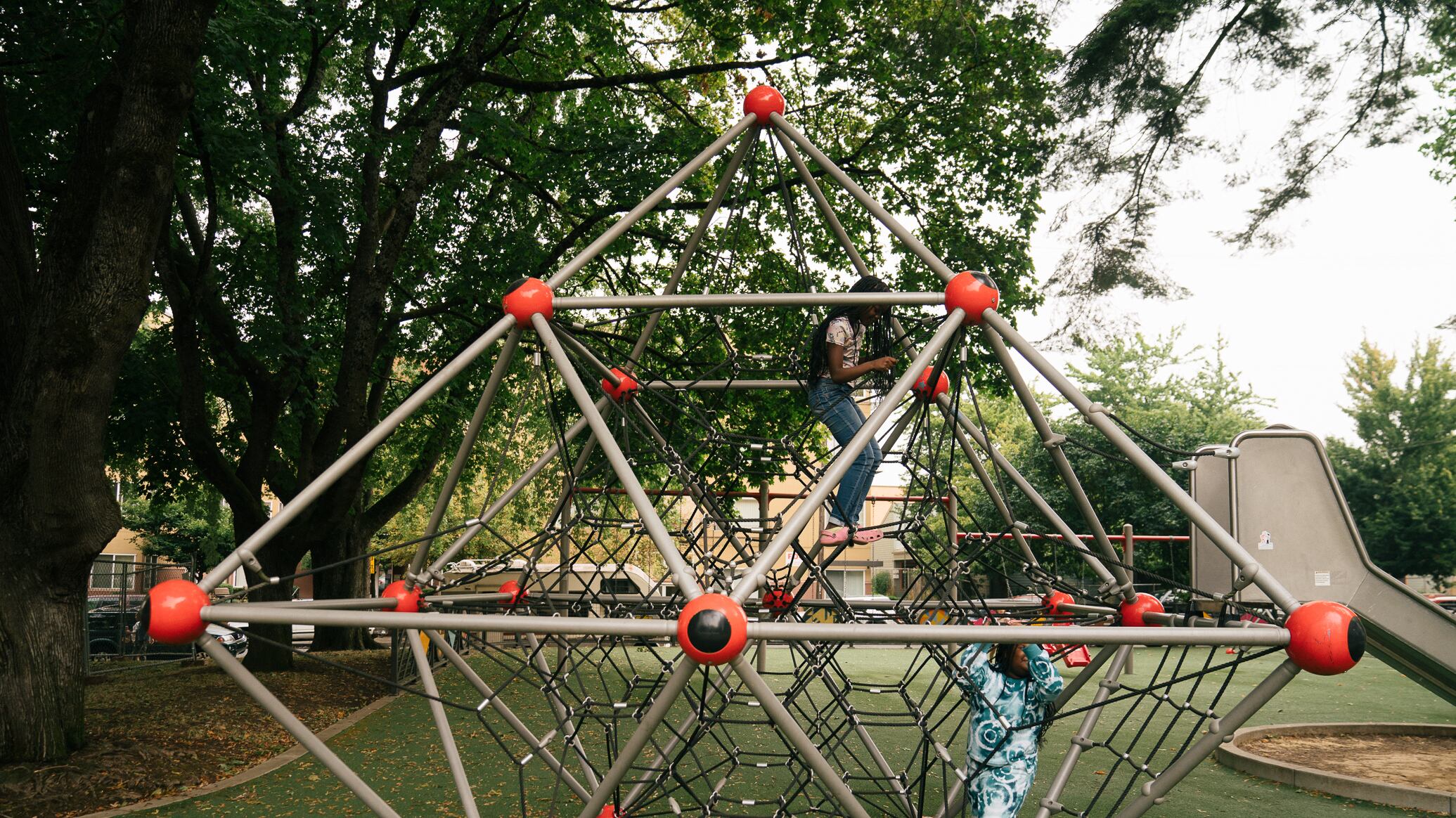

Anyway: I spent many sunny day lunch breaks in Dawson Park either playing on the swings or writing soup recipes in my sketchbook. Six years later, my kid would visit the children’s clinic across the street and afterward we would play on those same swings.

I have an affinity for the place because—unlike the parks in my neighborhood that slowly filled with white faces as development ramped up and Black and Brown families were displaced—Dawson Park has, for our lifetime anyway, always been a meeting place for Black community.

Now, against a pandemic, a decriminalization of drugs, the shifting landscape of gentrification and the magnifying glass that rightfully stays trained on the Portland Police Bureau, the historically Black neighborhood surrounding the park is experiencing upticks in violence and open drug abuse. This week’s cover story examines why.

Today, I welcome Sophie Peel to chat not only about how she and Lucas Manfield put together their in-depth look at Dawson Park in a post-George Floyd, post-Measure 110 Portland. I’ll also ask Sophie about the divergence in police response to downtown and response in the neighborhood around the park, and how lines can be drawn between the desertion of downtown and police response and the foreclosure of some of Portland’s large hotels.