It wasn't hard for prosecutors to identify Edward Thomas Schinzing.

On May 29, 2020—the first night of civil unrest in Portland following the killing of George Floyd—about 30 people entered the Multnomah County Justice Center through smashed windows.

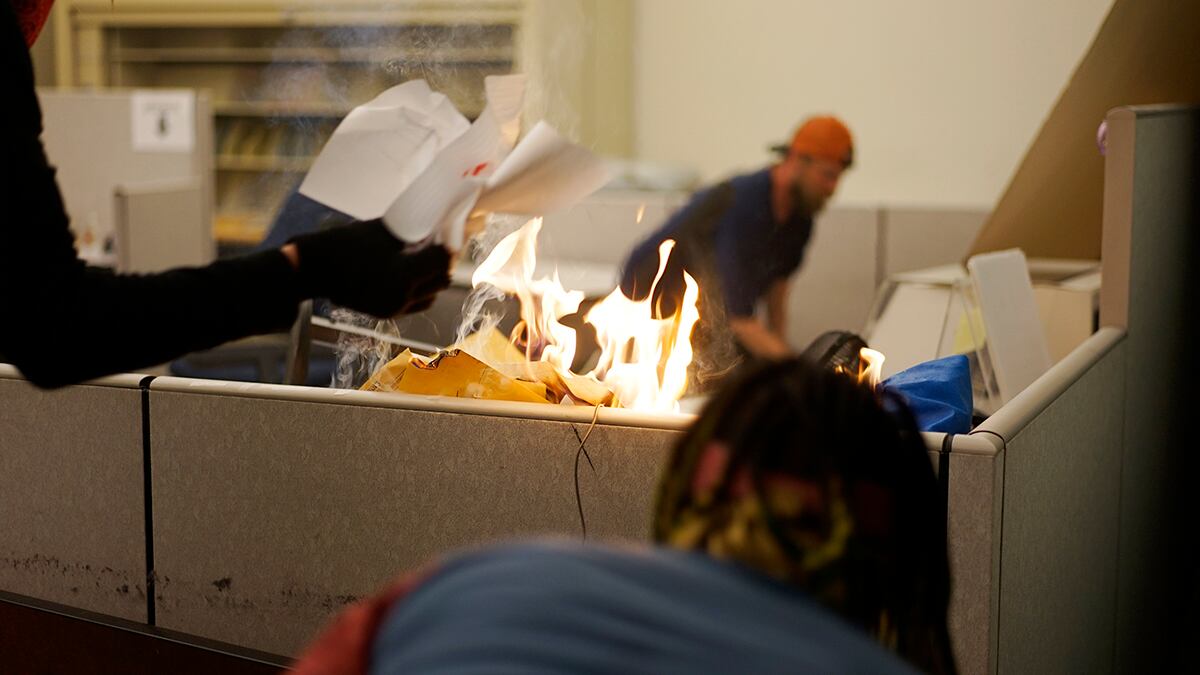

One of them was a 5-foot-8 white man who prosecutors say set fire to an office cubicle. Shirtless and sporting a backward orange baseball cap, the man was easily identifiable by a large tattoo inked across his upper back in large letters: "SCHINZING," it read—his last name.

Multiple video cameras inside the Justice Center recorded Schinzing, 32, as he "spread a fire near the front of the office by lighting additional papers on fire and moving flaming papers into a drawer of a separate cubicle," prosecutors say.

It was a slam-dunk case for the Multnomah County District Attorney's Office: the destruction of county property caught on camera. And county prosecutors are pursuing indictments for 47 people on felony charges related to protests this year.

Schinzing was indicted July 28 on arson charges. But the county isn't bringing the charges.

Instead, he's being prosecuted by the U.S. attorney for Oregon—that is, the feds. He's one of at least two protesters whose cases originated in the district attorney's office that have now been taken up in federal court, according to Multnomah County Senior Deputy District Attorney Nathan Vasquez.

That's remarkable because the destruction occurred on property owned by Multnomah County and the city of Portland. And the state of Oregon has harsher criminal penalties for arson than those levied by the federal government (the minimum sentence for arson is seven and a half years in state court and five years in federal court).

What also raises eyebrows among Portland lawyers is the feds' rationale for claiming jurisdiction: Because Portland and Multnomah County are recipients of federal aid, including COVID relief funding, the federal government has authority to prosecute crimes on those properties.

Charging Edward Schinzing in federal court isn't as dramatic as federal police seizing protesters in unmarked rental vans. But it marks an intrusion into the local criminal justice system that longtime observers say may prove even more consequential—because federal prosecutors may seek to make an example of more Portland protesters amid President Donald Trump's reelection campaign.

"I believe that Portland is Trump's petri dish," says Sean Riddell, a former Multnomah County prosecutor. "His people know, 'When we test a controversial policy out, we test it in Portland and see how it plays.' I think they're gonna see how this plays."

Members of the criminal justice bar say Schinzing's prosecution by the feds also reflects a schism in the local law enforcement community as newly elected Multnomah County District Attorney Mike Schmidt takes office.

When Schmidt ran against Assistant U.S. Attorney Ethan Knight in the first contested DA's race in Multnomah County in more than 30 years, it was a referendum on criminal justice reform.

Knight got $25,000 from the Multnomah County Prosecuting Attorneys Association, which added a withering attack on Schmidt, saying "because he has never personally tried to a court or jury any felony-level assault, sexual assault, domestic violence, child abuse or homicide case, he will be ill-equipped to set policies on how these offenses should be handled."

The region's law-and-order prosecutors and the Portland Police Association, which chipped in $20,000, strongly endorsed Knight. Schmidt beat him 75% to 25%. In the face of such a repudiation of the status quo, District Attorney Rod Underhill announced he'd leave office six months early.

Last month, Schmidt told WW he was still crafting a plan for prosecuting protesters, adding that change in America sometimes "took some property damage." On Aug. 11, Schmidt announced a policy of only pursuing charges against protesters who deliberately destroyed property, used force against another person, or threatened to do so.

But that didn't mean U.S. Attorney Billy Williams, who has been outspoken in his desire to see federal police on Portland streets, had folded his hand.

The timing of the charges caught the attention of several observers: The U.S. Attorney's Office announced it had indicted Schinzing just four days before Schmidt assumed his post on Aug. 1.

Schmidt tells WW he isn't familiar enough with the details of Schinzing's case to say whether he supports the indictment, and the U.S. Attorney's Office has not spoken to him about it.

"I haven't had conversations with [the feds] at all about this," Schmidt says. "I've outlined this policy [of] what I think is the right way to handle those cases. The fact that the feds are going in a different way is concerning to me."

During an Aug. 11 press conference, Schmidt did not dispute the feds' authority to determine they had jurisdiction in the Schinzing case.

Former Multnomah County Chief Deputy District Attorney Norm Frink, who had a tough-on-crime reputation as a prosecutor, says it would typically be odd for the federal government to prosecute someone for starting a small fire in a county building.

"Yeah, it's unusual. But the circumstances are even more unusual," Frink tells WW. "It's unusual that for 70-plus days, people have been permitted, with minimal law enforcement interference, to break the criminal laws over political animus. That's highly unusual. It's unsurprising to me that the only adult left in the room would exercise federal jurisdiction when he can."

Edward Schinzing allegedly started the fire more than a month before President Trump dispatched federal agents to Portland. And the damage occurred in a building owned jointly by the county and the city of Portland.

In a probable cause affidavit, federal officials offer two reasons why they can bring the case.

First, on May 29—the date of the fire—22 of the 289 inmates held in the Justice Center faced federal charges. Some of their paperwork was stored in the building.

The second argument the feds make for jurisdiction is that Portland and Multnomah County are recipients of federal funding, namely from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act, passed by Congress in March.

Special Agent Cynthia M. Chang of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives wrote in the affidavit that "Schinzing maliciously damaged and destroyed…by means of fire a building and other personal property belonging to Multnomah County and the City of Portland, which are both institutions and organizations receiving federal financial assistance."

Portland lawyers find that argument unusual.

"Based on that rationale, federal authority would exist anywhere in Portland," says Jason Kafoury, a Portland civil rights lawyer. "It's also a scary precedent, because it's opening the door for federal authorities to arrest Portlanders anywhere, anytime."

Schinzing's attorney, public defender Ryan Costello, declined to comment on the case. Oregon Public Defender Lisa Hay says she can't comment on any specific case, but speaking generally, she says it's important for the federal government to mind jurisdiction when prosecuting cases.

"We always look to hold the federal government to act within its authority," Hay says, "and to only bring prosecution where they have jurisdiction."

The timing of the indictment also raises questions whether employees in Schmidt's office helped take the case out of their new boss's hands.

Emails obtained by WW via a public records request show that the DA's office helped investigate Schinzing before the U.S. attorney took the case. In emails, a DA's spokesman thanked the U.S. Attorney's Office for mentioning Multnomah County in the press release because "our office did contribute to the investigation."

But neither agency will say who exactly referred the case to the feds or why.

Kevin Sonoff, spokesman for the U.S. Attorney Williams, declined to comment. "The U.S. Attorney's Office coordinates with district attorney's offices throughout Oregon on cases in which both jurisdictions could bring charges," Sonoff wrote.

Kenneth Kreuscher, a criminal defense lawyer in Portland, says the feds probably took the initiative to prosecute Schinzing.

"I would be highly surprised if the Multnomah County district attorney asked the feds to step in on a case involving a fire at the Justice Center. I would be shocked," Kreuscher says. "The Trump administration has spilt gallons of ink and made a lot of statements saying people involved in these protests need to be punished."

It's unlikely Portlanders will feel much pity for Schinzing. He remains in custody at the Multnomah County Jail, where he's been held since July 2 following an arrest for violating parole after being convicted of assault this spring for attacking his domestic partner and her child.

But Kreuscher says the timing of the case bears watching, as the president remains fixated on making an example of Portland and liberal leaders like Schmidt.

"It's not surprising to me that they are trying to get involved for political reasons in what I think are local and state cases," Kreuscher says. "The cases in Portland and the uprisings in Portland have become a political football that's being used by the Trump administration."