On Saturdays, Ramzy Farouki often rides the MAX Red Line into downtown. He uses the ride to clear his mind before he stands in Terry Schrunk Plaza to talk about the plight of a country he can no longer visit to anyone who will listen.

Farouki, 35, is a Palestinian raised by parents who immigrated to St. Louis. He moved to Northeast Portland in 2010 and works construction and landscaping jobs.

He cannot go home to Palestine. So he brings Palestine to downtown Portland.

“I see how much culture and heritage is lost in each generation, and that’s why I try to educate,” he says. “It’s my love for my heritage in the face of seeing its erasure.”

He isn’t the only immigrant activist in Portland feeling sick about home. For many, protesting downtown is a way to feel they are doing something for their homelands, many of which are now under siege.

In the national imagination, Portland’s protest scene is 25 furious teenagers in black ski masks demanding police abolition around a dumpster fire.

But for much of this spring, Portlanders strolling along the Willamette River or near City Hall have instead encountered a very different sight: first- and second-generation immigrants carrying the flags of their homelands and sometimes potluck meals.

Portland is not diverse compared with most American cities. But to the casual observer, this spring has witnessed a blooming of small communities, in groups of 20 to 200, who gather downtown each weekend amid rain clouds and cherry blossoms, sharing with the rest of us the unthinkable bloodshed they see occurring in their home countries.

In Myanmar, where over 805 pro-democracy protesters have been killed by government forces as the nation teeters on the brink of civil war.

In Gaza, where a fragile cease-fire between Israel and Hamas occurred only after Israeli military forces killed 248 people in two weeks.

In Colombia, where local law enforcement has engaged in extrajudicial killings of dozens of protesters.

For many, the violence has effectively locked them out of their homelands. “I don’t think I can go home until this is all over, because it is too dangerous,” says Tori, an Oregon State University student who hasn’t seen her family in Myanmar in two years.

And so, from the small Palestinian, Colombian and Myanmar communities that live in Oregon has emerged a passionate, peaceful and distinctive kind of protest.

They defy the common conception of what a Portland protester looks like. They ask that a city weary of marches and unrest pay attention to injustices that don’t feature cops or Donald Trump. They found inspiration in the methods and message of the Black Lives Matter movement and now they ask that people listen to their story, see what they see, and consider the role our elected officials can play—and have played—on a larger, global stage.

On three recent weekends, we mingled with three movements spearheaded by first- and second-generation immigrant organizers. We found Portlanders of all ages taking to the streets to protest the injustices closest to their hearts yet happening thousands of miles away.

Myanmar Revolution Day

Saturday, March 27, at Pioneer Courthouse Square

On a bright, cold day in March, a golden peacock on a crimson background flew proudly in the wind.

That’s the symbol of the National League for Democracy, the political party overthrown Feb. 1 by a military coup in Myanmar.

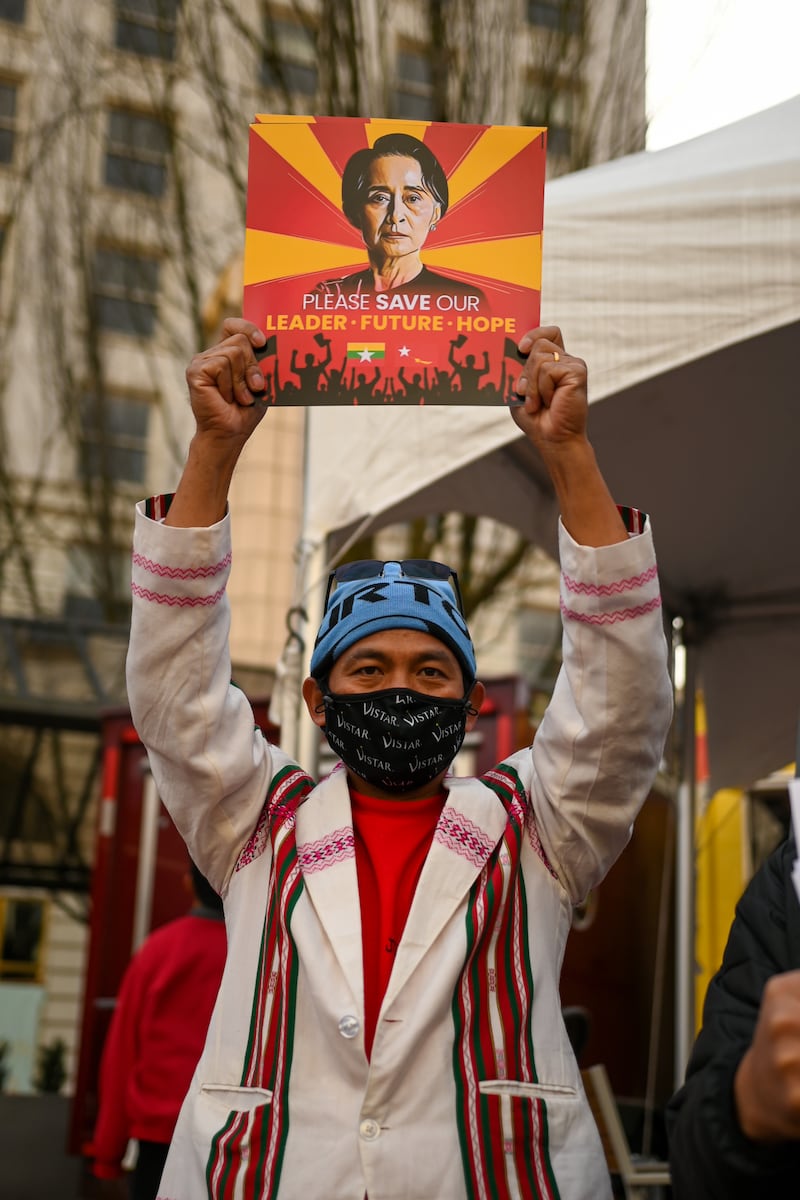

Portland’s Burmese community was gathered beneath the brilliant flags, representing the Shan, Zomi, Kachin, Kayah and Rohingya—all ethnic minorities in Myanmar. (The country was once called Burma, and the name remains in dispute.) They stood together on Pioneer Square’s curved brick stairs, speaking out against Myanmar’s new military dictatorship.

This was the fifth gathering in Pioneer Courthouse Square since Myanmar’s military arrested its president and assumed control over the government on the first of February.

In Pioneer Courthouse Square, a line of college-age immigrants led chants.

“Free our president!” one yelled.

“Aung San Suu Kyi!” the crowd responded—the name of the imprisoned leader.

They simultaneously threw up a three-finger salute, a gesture originating in the Hunger Games movies but now used by protesters in streets across Southeast Asia.

One of the hundred hands raised belonged to Tori, an 18-year-old international student at Oregon State University. She’s in her second year of a pre-medical program and juggles her studies and activism quite well. Her grades are up. “But my friends have been telling me to take a break since I have no time for them,” she admits later in an interview.

She came to the U.S. on a merit scholarship to OSU. She was born and raised in Yangon, the capital of Myanmar. “I did not see democracy growing up,” she says. “That is something I don’t want for my younger siblings.”

Her family still lives in Yangon—the heart of the unrest.

“My parents don’t know that I am involved in the activism here. I didn’t tell them because I don’t want them to worry,” she says. “I miss them a lot.”

Increasing overreach surveillance on social media platforms by Burmese authorities creates new risks for returning Burmese citizens. Those engaged in activism overseas face possible arrest and detention, according to Amnesty International. Tori says she’s too worried to go back to Myanmar, despite having deleted much of her online social media presence.

For Tori, this fight is not only for a democratic future in Myanmar, but also for her right to return home. “We can’t lose,” she says. “We can only lose if we give up.”

Oregon has one of the largest immigrant populations from Myanmar on the West Coast. The most recent census data, from a decade ago, said just over 1,400 Burmese lived in the Portland area.

Yin Oberg says the number is much higher: About 10,000 in the growing Burmese community currently live in Portland. “Anywhere from 122nd Avenue to 160th Avenue all the way down Division Street, there are a lot of Burmese people. Many came as refugees in 2005-2006,” Oberg tells WW. “These refugees have been in the refugee camps for more than decades on the border of Thailand and Burma. Some kids were born at the camp and have never lived outside of barbed-wire refugee camps.”

Oberg would know: She helped resettle many of them, while working for Lutheran Church Charities.

Oberg is a mother of three, the daughter of a United Nations diplomat who made Portland home more than 33 years ago. She now works for Multnomah County’s developmental disability services in downtown Portland. On weekends, she attends the weekly Myanmar pro-democracy marches in downtown Portland, where students raise money to send home through apps that are difficult for the Myanmar government to trace.

On a sunny May weekend, Oberg was one of several vendors selling shirts and food in Lents Park. She stood behind a plastic folding table laden with a large inventory of Myanmar pro-democracy T-shirts, many emblazoned with symbols of the Federal Army of Myanmar, a rebel group currently resisting the military regime.

“I spent about $2,000 out of pocket to buy the shirts,” she says. “I see dead bodies on social media every day. Kids, 15,16,17. I have three kids of my own. I think of how lucky they are.”

Oberg managed to donate $280 to the cause after a day of sales of T-shirts and her homemade goat curry.

“I can act like nothing’s happening,” she says. “I am settled here, my children are safe here, but I feel heavy in my heart if I do.”

Nakba Day Call to Action

Saturday, May 15, at Terry Schrunk Plaza

“Free Palestine! Free Palestine!” a crowd of 400 people chanted. They filled Terry Schrunk Plaza and then some, spilling back into the trees and shrubs. That’s nearly as many Portlanders who listed Palestinian as their ancestry in 2019 census data.

Ramzy Farouki joined them briefly in the chant, before opening the rally by comparing the Pacific Northwest land he was standing on to his own. Both, he said, were stolen.

“Remember, as Palestinians, we will always stand with you and your struggle for decolonization,” he declared.

The May 15 rally was the second pro-Palestine rally in Portland since Israeli military actions in East Jerusalem on April 11 sparked a rapidly escalating war in Gaza. It was also Nakba Day: the globally observed anniversary remembering the mass exodus of upward of 800,000 Palestinians who were displaced after the creation of the state of Israel.

Throughout the rally—between speakers—Farouki read a fraction of the names of the 400 villages the Palestinian people fled in 1947 to 1949. He ran out of time to read them all.

Farouki is founder and director of the Center for Study and Preservation of Palestine, a tiny educational center in Northeast Portland. “Personally, I think just being a Palestinian places me into the activism sphere,” he says. “It shouldn’t be activism to be for the human rights of your people, to be against ethnic cleansing and genocide, to be against the occupation of your homeland.”

Far more than most rallies by immigrants, the Palestinian cause interlocks closely with the city’s leftist politics. Efforts to divest from companies doing business with Israel’s government have regularly been a contentious issue in City Hall and a mainstay of campus politics at Portland State University.

That—along with the horrifying images emerging from Gaza City over the past two weeks—may explain why the crowds at Palestinian protests are larger than those at other immigrant rallies.

Despite a May 21 cease-fire in Gaza, the crowds returned a week later, gathering in front of City Hall to chant slogans and march through Portland’s downtown. This time, 250 people joined in.

“A cease-fire has been announced. We all know that’s bullshit!” Willamette University student Abdul Ali shouted into a stranger’s megaphone. Ali said his grandparents fled Palestinian villages and he grew up as a refugee in Jordan.

“Boycott Israel!” he demanded. “Your workspace. Your campus. Get that shit out of there!”

At a downtown rally a week later, Olivia Katbi-Smith held a petition for such divestment. It asked Portland City Hall not to renew a security contract with the Florida-based corporation G4S, due to that company’s ties to Israel.

Katbi-Smith is co-chair of the local chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America. Katbi-Smith is of Jordanian descent, but the organization she coordinates for Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions is Palestinian-led and was founded by Palestinians in 2005.

After a failed attempt to get the hundreds sitting on the plaza’s steps to sign the petition, another young activist, an Oregon Health & Science University nursing student who asked WW to use only her first name, Maysa, walked to the center with a bullhorn.

“If you have your phone, hold it up,” she says. “We’re all going to go sign the petition together!”

Maysa’s family is from Iran, but she and a number of the other organizers are part of a Muslim activist organization called Hurriyah Collective. Their focus is on mutual aid—projects like toy drives and serving hot meals to the houseless.

“Always fight for the oppressed and the marginalized,” she says. “That’s a very big thing in Islam.”

If some of this sounds familiar from other protests, it should. “We have to give a lot of credit to the Black Lives Matter movement,” Ali points out later. “They set the foundation for really widespread knowledge being passed on via social media. And engaging the younger population to become a part of these movements. We owe that turnout today to all the people who’ve been putting in work before us.”

Colombia Peaceful Protest Rally

Saturday, May 8, at Tom McCall Waterfront Park

Next to the sophisticated activism of Palestine’s supporters, Portland’s Colombian community is just getting warmed up. On an overcast day in Tom McCall Waterfront Park, 150 gathered—most decked out in the vivid yellow, red and blue of the Colombian flag.

They marched on downtown sidewalks to Pioneer Courthouse Square and briefly cumbia-danced before speeches began: charged calls to action or denouncements of the violence Colombia’s police and military forces have meted out to protesters.

Dia Murillo, a therapist who grew up in Cali, Colombia, led the group in a meditation where they held tea lights and sent good wishes to Colombia.

About 150 Colombians were at the event, 15% of the population of Colombians living in the Portland area, according to the 2010 census.

“One of the goals of the march was just to see Colombians in the city,” Murillo says in a later interview. “Who are they? Who would come? We wanted to have Colombia present in our hearts, but not specifically engage in conversations—who is on the right, who is on the left, who is for and against the government. You might be surprised how many different views there were in that crowd.”

Unlike Palestinian protesters, who are united in their outrage toward Israel, this group of Colombians is mixed in its attitudes toward the Colombian government, which is locked in a violent struggle with protesters. Protests in Bogotá started April 28, in response to a proposed tax change that would fall heaviest on low- and middle-income communities.

“Basic foods like eggs, basic needs like tampons would be taxed at 19%,” Murillo says. Colombia’s militarized police came down heavily on the demonstrations, firing live ammunition into crowds of peaceful protesters.

Murillo says some Colombian immigrants, fairly conservative in their politics, still attended the march. “They like the government, but don’t think people should be shot for protesting. Their attendance was really brave and humble.”

Murillo’s mother still lives in Cali, and Murillo describes the past two weeks as spent “hiding under tables” for portions of the day. “Shootings. Gunfire. She can see buses of police coming into the neighborhood. It isn’t the most safe neighborhood, but she’s never seen anything like this.”

All of the Colombians WW interviewed had people back in Colombia whom they worry about. But not many were worried for themselves, outside of the nagging concern that activism could somehow lead to deportation. “I was very afraid of being taken or deported,” Murillo admits.

Even though the Colombia solidarity march, which she helped plan, walked on city sidewalks instead of marching in the street, she looked around for police. Murillo didn’t know who in the crowd might be undocumented, and she worried about her residency status if she faced legal problems. “I was very afraid of the cops showing up,” she says.

More than one protester described to this reporter the psychological toll of being so far away and feeling so helpless.

“There are some moments where I’ve been so paralyzed,” Juliana said. She requested that WW use only her first name. Much of Juliana’s every day is consumed with making social media posts about the situation in Colombia or calling attention to other social justice causes. But there are days when she says she can’t bear to look at anything online. “Yesterday I went fishing and I think that all that frustration made me catch a 22-inch fish!”

Murillo, on the other hand, views her online activism as a way to care for herself. “People have to see, people have to be informed. I normally take 10 minutes of my day to talk about it or educate people. Not just marches, but the war on drugs. The ’91 constitution. Changing how people see Colombia.”

For now, the future of this slowly coalescing community is focused on mutual aid rather than marches. Angela Barrios, an environmental science major at Portland State, says the volunteering she did during the 2020 wildfires taught her the simple value of sending money to people who need it, no strings attached.

She’s planning a Colombian food pop-up fundraiser. “Families are having a hard time getting access to food, water and medical supplies,” Barrios says. “They’re still in a pandemic. They haven’t had any assistance. If I can send them some money by sharing a bunch of food that I grew up eating, it’s the least I can do.”