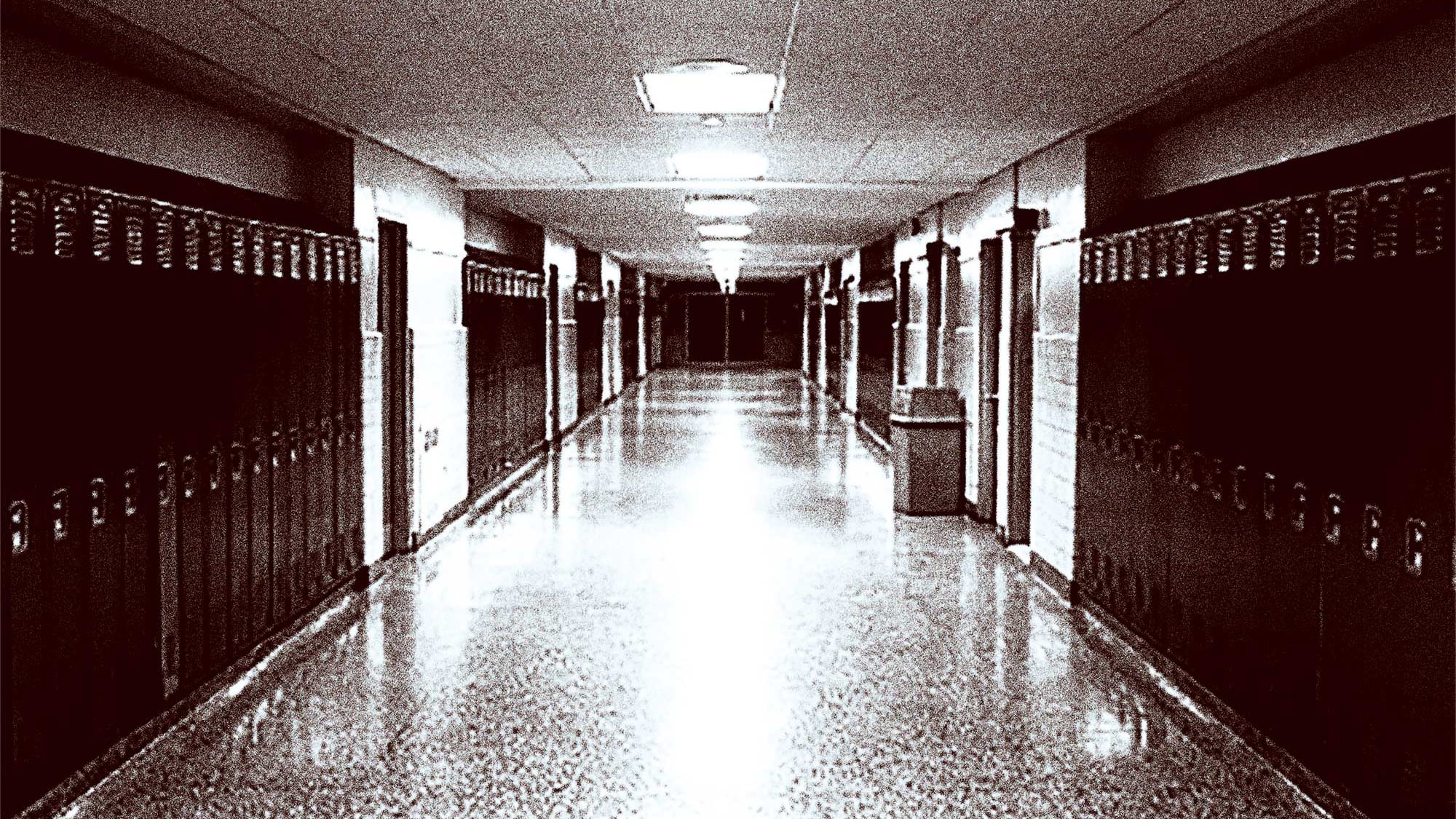

Nine times in the past 13 months, students in Portland Public Schools have been told to gather in classrooms and sit silently in the dark—because the school was in immediate danger.

Each time, it was a false alarm.

The unnecessary school lockdowns, which parents and teachers describe as frightening and stressful, have already happened twice this school year: once at Buckman Elementary School on Sept. 30, and once at Roseway Heights Middle School on Oct. 2. The Roseway Heights incident resulted from a communication error between staff, while Buckman's was caused by the accidental tripping of the school phone's emergency system.

In both cases, students were instructed to remain completely silent. If they weren't already in a classroom, they knew either to find one to duck into or leave the school entirely. Meanwhile, teachers knew to bring students into their classrooms, lock the doors, cover the windows and turn off the lights.

Suzanne Cohen, president of the Portland Association of Teachers, says the mistakes can be terrifying. Students across the state regularly engage in planned lockdowns, sometimes called active shooter drills (along with fire drills and other emergency preparations). "Even the drills, when you know they're drills, are super-emotional and powerful," she says.

But when a school goes into lockdown by mistake, students and teachers believe it's real.

"You're very scared and you question everything. Every move you make is for your safety and the safety of the students," Cohen tells WW. "And then finding out it was an accident? I guess it's better than finding out it was real."

It's unclear whether the false alarms are occurring at a higher rate than in past years, because PPS would not release data prior to 2018.

But the pattern raises questions about how the school district should handle the dystopian reality of gun violence in America.

Amanda Russell, a parent of a Buckman student and co-president of the school's PTA chapter, says lockdowns are more disturbing than other emergency procedures. "Just the thought of children hiding and doors being locked," she says, "it just sounds stressful to me."

Russell says she didn't realize how often it was happening districtwide: "I wish the number of false alarms had been communicated to us, because that's troubling. Lockdown drills are already stressful enough, and now false ones are occurring? At some point, something needs to be fixed."

Portland Public Schools argues quick access to lockdown alarms for school staff is a priority because it would help students survive an active shooter at a school.

"We do understand that an inadvertent lockdown can cause trauma," says district spokeswoman Karen Werstein, "and our mental health services team works closely with our security team to provide trauma-informed resources to schools to help support students when needed. No system is perfect, and it's regrettable that there is ever a situation where an inadvertent lockdown could happen."

The district tells WW that lockdowns are initiated when a staff member dials certain numbers into a district phone. Staff are trained how to do it, but it's designed to be easy in case of an emergency.

"Because safety is our first priority at PPS, we want to make sure that all staff and rooms in a PPS school have the ability to activate a lockdown," Werstein wrote in an email to WW. Because of that, she says, every phone in the district can activate a lockdown message.

The district wants to make activating a lockdown "as accessible as a fire alarm," Werstein says, so every phone in the district can send a lockdown message, and it doesn't require entering a passcode. (It does include a prompt asking if the staffer really wants to activate a lockdown.)

That could explain the main cause of accidental lockdowns, she adds. "Typically, an accidental lockdown occurs when a staff person presses the wrong series of buttons on a phone."

Lockdowns became commonplace in U.S. schools following the 1998 Thurston High School shooting in Springfield, Ore., and the 1999 Columbine High School shooting in Colorado. They are designed to secure students and staff when there's a threat inside the building. That can include an active shooter, a student posting something threatening online, or a bomb threat.

An Oregon law passed in response to the 2012 shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Conn., requires public schools to conduct two lockdown drills a year. At PPS schools, they're practiced each year in the spring and fall.

But some of the lockdowns regularly occurring at PPS campuses aren't drills—they're false alarms. Cohen of the teachers' union says when a lockdown is activated, a teacher probably figures it may be for an active shooter.

"When we're locking down the entire school, there's a threat inside the building. You can try to imagine another scenario—it could be someone else who's violent with a weapon," Cohen says. "But given the timing of when we started doing these drills, the purpose is clear."

Some parents say the psychological toll of false alarms is too high to justify.

Mingus Mapps, another Buckman parent, says his youngest son, Coltrane, 9, had a strong emotional response to the school's accidental lockdown in September. His son hadn't understood the lockdown was an accident—he thought an intruder had entered the building.

"He was super freaked out. He was traumatized," says Mapps. "It was one of those moments where as a parent, you're freaked out, your heart skips not one beat but, like, three beats."

According to Mapps, a candidate for Portland City Council, lockdowns are frightening because of their association with school shootings.

He wonders if the system is proving counterproductive.

"I do think it contributes to a culture where our kids do kind of expect to get shot in their classrooms," Mapps says. "And that's not a good thing at all. It was a situation where technology failed us and, at a broader level, society's kind of failed us."

For Cohen, the accidental lockdowns are troubling, but she thinks the more important issue is gun control.

"There shouldn't be any need to have this practice or the skills it's teaching us at all. The notion that we have to be prepared for such incidents is outrageous," Cohen says. "This isn't something that happens in schools in every nation. This is a unique-to-America problem."