In a memo sent to the Oregon Legislature last week, the Oregon Parent Teacher Association offered a competing narrative to data from Georgetown University that showed increased education spending had not resulted in better outcomes for Oregon students.

The data from the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown, which WW first reported on Wednesday, mapped increased spending alongside student outcomes from the Oregon Statewide Assessment. While education spending increased by 80% between 2013 and 2023—up to $17,100 per student—results have flatlined since pandemic lows. On the statewide exam, 42.5% of students demonstrated proficiency in English and language arts, and 31% in math. Those scores are lower for Black and Hispanic students.

Dr. Marguerite Roza, director of the Edunomics Lab, told WW the data indicates Oregon does not spend effectively, and needs to track its outcomes more closely. But state legislators on the Joint Ways and Means subcommittee on education were skeptical of the data, raising concerns about test scores as a measure of outcomes.

They have backup from the PTA. In a 10-page memo shared with WW, the association says the Edunomics presentation “included some statements, graphs and data that we believe require context and in some cases corrections.”

The document offers several objections to the Edunomics presentation. First, it argues that parts of the Edunomics charts miss context. For example, the PTA notes that Oregon experienced a dramatic increase in funding between 2013 and 2023 because the state was coming off the 2008 recession in its 2011-13 biennium, and spent less on education than it had in 2007-08. “By starting the chart in 2013, Edunomics Lab has chosen a particular low point in school funding as a starting point,” it notes.

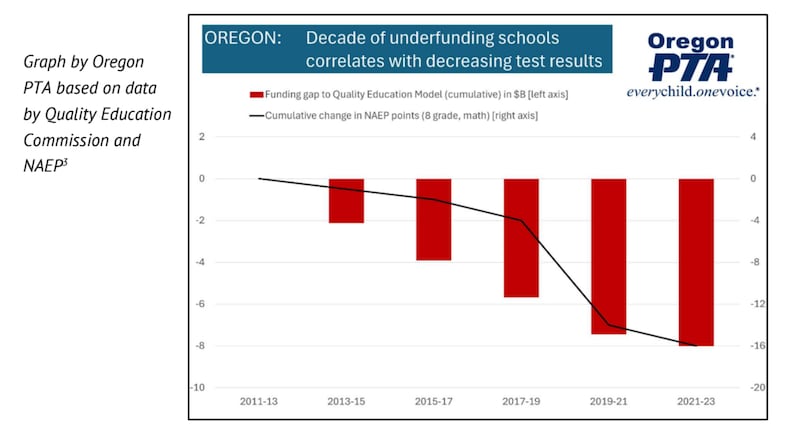

The statement also suggests that inflation growth is not the best comparison with increased spending (Edunomics found education spending had far outpaced inflation in the state). Instead, the PTA wrote a better comparison would be the Quality Education Model. That’s a state model that produces a number for the amount of money needed to fund a quality education, though the Legislature repeatedly falls short of providing it.

From 2011 to 2013, the gap increased by $8 billion, the PTA says, and eighth grade math scores on a nationwide exam went with them, down 16 points between 2021 and 2023.

The association added that even as Oregon’s school staffing has increased over the years, the state has lost 700 teachers since 2019. That could explain the decline in outcomes even as staff generally has risen, the PTA contends.

It also argues that without increased funding, test scores could have been worse. “We don’t know what test scores would be like if expenditures hadn’t increased,” the document reads. “It could be postulated that without the additional funding the drop in test scores might have been worse.”

“While we are not seeing the recovery and progress we would like to see, this might not be caused by district investing inefficiently as Edunomics Labs suggests, but simply a reflection of the depth of the crisis we are seeing with our students where the increase in needs outstrips the increase in funding,” it continues.

Roza, the Edunomics Lab director, tells WW that the lab has not suggested that money doesn’t matter, or that increased spending can’t correlate with better results. “We agree that no one can know what might have happened without the funding that did get delivered,” she says. “Of course, there are lots of variables that matter.”

“That said, when comparing Oregon to other states, it is hard to ignore that other states have been more successful in leveraging incremental dollars to drive progress for students,” she says. “We’re not suggesting that the state roll back funding gains. Rather, going forward, the challenge for the school system is to reflect on existing investments to explore whether there are ways to ensure more success with students going forward.”

The PTA argued that Oregon has started making steps in the right direction, and that systemic change takes time. It pointed out that some student groups who have been targeted with money from early literacy funding or high school career technical education are not yet evaluated in state exams. (Most students who benefit from early literacy funding have not yet reached third grade, the first year for state testing.)

The PTA’s memo largely left unaddressed the question of why other states saw stronger results with their increased spending. (“There is an important ongoing debate about which pandemic responses have, in hindsight, proven to be more effective than others,” the memo noted, “and Oregon PTA and our members continue to welcome opportunities to review state and district spending.”) The Oregon PTA did not immediately respond to additional requests for comment from WW.

Roza said the PTA’s message seemed to defend the status quo.

“We’re disheartened by the suggestion that patience is needed as ‘systemic change takes time,’” Roza said. “Today’s students don’t have time. Are we certain that if we stay the course, scores will turn around? I’d argue that more urgency, not patience, is needed to ensure that today’s students have a chance at the future we all want for them.”