Nobody wants to think about children being hurt or killed during an earthquake. It’s not my idea of pleasure reading, and it surely isn’t yours, either. If you’re opening this story on the bus or over morning tea, you may be tempted to close the paper and go back to doomscrolling.

But the truth is that our earthquake is coming, whether we think about it or not. The Cascadia subduction zone earthquake is a tectonic inevitability, thanks to plates in the earth’s crust that lie beneath the Pacific Ocean just off the Oregon Coast, leaving Portland vulnerable to what could be one of the worst natural disasters in the history of North America.

It’s this simple: If we don’t understand the risk, we cannot prepare. And there’s no risk as important to think about, no matter how unpleasant, than our brick school buildings.

I started writing a novel about the “Big One” in 2019 because I found myself lying in bed at night, overwhelmed with anxiety about the earthquake. How bad would it be? What would our city look like after? How long would we have to wait for help? During my research, I was horrified to learn that we have nearly 20 schools (and hundreds more churches, apartments, and office buildings) in Portland that could collapse during an earthquake.

I became obsessed with the topic—how dangerous are these schools and what can be done about it?—and I have spent years researching. I’ve done dozens of interviews, attended an earthquake drill at Sabin Elementary, met with structural engineers, and dug into hundreds of pages of Portland Public Schools documents obtained through public records requests. This led me to continue pushing the school district for answers, and ultimately to PPS releasing its latest seismic assessment to WW (see “Shake Shacks”).

In the following pages, I examine the issue of how dangerous these unreinforced masonry schools are from two angles, fictional and reported, in the hopes of bringing clarity, if not much consolation.

In my novel, Tilt, the earthquake strikes in the late morning, on a weekday. My protagonist, Annie, 37 weeks pregnant, is shopping at IKEA for a crib. By sunset, she has completed a crosstown walk to the Buckman neighborhood in the company of Taylor, a young mother desperately trying to find her 5-year-old daughter.

This excerpt takes place at a fictional URM school—Columbus Elementary—which I placed at Revolution Hall. In other words, it is not a real school, but it does provide my best understanding of what will happen to a brick school after a large earthquake. This scene is based on interviews I did with first responders who have been on site at collapsed schools and members of the Portland Neighborhood Emergency Team, along with first-person accounts from past earthquakes.

The decision to run this excerpt is one that the team at Willamette Week and I spoke about at length. Ultimately, we decided that the need to be informed must come before the desire to be comfortable. As a journalist, a Portlander, and the mother of two kids headed into PPS this fall, I ask you not to look away.

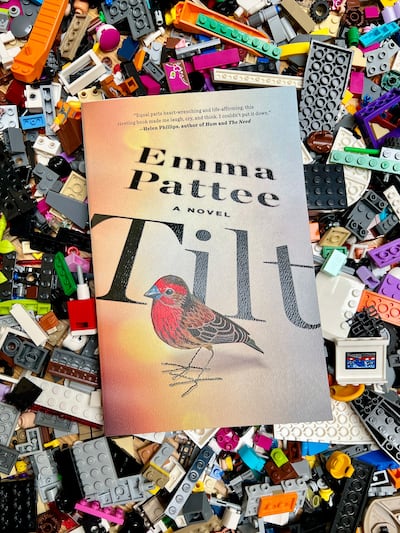

Excerpted from Tilt. Copyright © 2025 by Emma Pattee. Excerpted by permission of Marysue Rucci Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The south side of the school is flattened, as if a giant foot had come along and stepped down, pressing the entire structure into the ground. A blanket of bricks spread across the lawn. People are standing in clumps in the street and on the sidewalk. Adults crying, holding each other. Worried faces turned towards the building. Like a scene from a school shooting, how everyone gathers in the parking lot and waits.

Taylor has disappeared into the mass of people swirling around the school steps and lawn. A banner floats along the school gates, advertising free lunches. The north half of the school is still standing but tilted, looming over us all.

A woman stands at the top of the school steps, her shoulders visible above the crowd. Dirt on her face, on her shirt. She has glasses on a chain and she’s holding a radio in her hand and yelling something about staying calm, but I can’t hear it over the crowd. The noise hits me in the face, pushing me backward, parents yelling the names of their children, kids crying, everyone talking over everyone all at once.

Piles of debris and brick all over the lawn. Jungle gym: uprooted. The slide hovering in the air. Kids everywhere I look, sitting on the debris of the building and standing by the fence, staring off into the distance. Crying. Their faces and hair coated in dust. Blood that shows up black on gray limbs. A boy with zebra print glasses. A man wearing a safety vest leans over a child. A girl rocking back and forth on a swing set, her legs dragging on the ground. Behind her, a shape on the grass. A tiny shape covered in a blanket.

All over the field, sheets of colored paper. I pick one up. A shaky outline drawing of a stick figure with a little speech bubble, in a child’s awkward scrawl: Oops I slep on a bananana peel.

Everything is too bright, too sunny. There’s sweat stinging my eyes. Whatever is about to happen, I don’t want to live it. A yellow shirt. There she is. Taylor. When she sees me, she starts sobbing, bent over, her back heaving.

“Oh my god oh my god oh my god,” she is saying.

“Just breathe,” I say. Or maybe my lips are moving, but no words come out.

“I can’t find her...,” Taylor says, nostrils flaring. She looks crazed.

“It’s gonna be okay,” I say. “We’re gonna find her.” My own mouth can barely form the words, that’s how stupid I sound.

A man walks by us holding the hand of the boy with the zebra glasses. The man and I meet eyes, and he looks away, guilty.

I scan the field looking for a blonde head. She’s gotta be here somewhere. The kids blend into a mass of bodies and noise.

“What’s she wearing?” I ask.

“Shorts, blue shorts. Pink sneakers,” Taylor says, running her hands through her hair. “And a shirt with a, a rainbow, and a necklace from Moana.” She cups her hand to show me. “It lights up, it’s a little plastic shell.”

We start walking in wild patterns through the field. Tripping on bricks and lunch boxes. Taylor locked onto my arm. Kids everywhere, and both of us looking around frantically for a face.

I mean, what did I think? That the kids would be lined up in little rows wearing name tags? I’m so stupid, so fucking stupid. Tears in my eyes, breath caught in my throat, heart caught in my chest, body caught suspended in this horrible moment.

The woman with the radio is screaming at everyone to stay calm. “It’s been hours!” someone yells from the back of the crowd. Then all the voices are overlapping, faster and louder.

A man wearing a helmet breaks through the crowd, grabbing his head. “This is fucking crazy,” he yells. “My kid is inside there!” Hitting the sides of his face. “My kid!” He crouches in the grass and rocks back and forth on his heels.

“We need to wait for the search and rescue team,” the woman with the radio yells. “They have sensors and hydraulic...” She looks terrified, the muscles in her throat bulging. “Please, trust me,” she says, her hands steepled in prayer around the radio.

“What, are we gonna leave them in there all night?” a woman in a baseball cap screams.

Taylor starts rocking back and forth and making these soft little groans. What did that earthquake guy say? That it could be days before rescue teams can reach people.

Taylor starts talking fast and quiet, almost under her breath, and I have to lean close to her to hear what she’s saying, “Children have always died, you know. People think that’s so crazy, a kid dying, such bad luck, couldn’t ever happen to me, but they are such fucking fools. Kids die all the time. Just like it’s no big deal. Just like that. No big deal.” Taylor’s nails dig into my arm so hard I have to will myself not to pull away.

“She’s in there,” she says, nodding towards the collapsed building. “They’re never going to find her. She likes to hide. She’s very small.” Her voice breaks on the last word. “Her wrists are like this.” She holds two of her fingers an inch apart. We both stare at her nails, little pink daggers, shaking in the air.

I can hear someone wailing.

“We’re gonna find her,” I say.

“I have to go get her,” she says, turning towards the part of the building that is still standing.

I grab her arm. “No, you can’t go in there. You heard that lady.”

She presses her palms to her eye sockets and moans. “This can’t be real,” she whimpers. “This can’t be happening.” She walks away from me and rests her forehead against a tree trunk. I can see her mouth moving, but I can’t hear what she’s saying.

This is the worst place on earth.

I close my eyes, just for a moment, just for a moment. Even with my eyes shut, the tears slip out and drift down to my mouth, my chin, my sweaty neck.

“What is that?” A girl is standing in front of me, pointing at the green caterpillar, which is poking out of my pocket. She has red hair and her wrist is covered in friendship bracelets with those little white letters.

I pull it out to show her.

“Caterpillars have exoskeletons.”

I am really not sure what to say. “Cool.”

“I’m waiting for my mom.”

I try to look reassuring. “I bet she’s almost here.”

“She works in a bank.” Her eyes fill with tears.

“Listen.” I pull the caterpillar apart and it starts to play its quiet little melody. The girl stands there blinking, listening, and then reaches out and puts her hand on my leg. The warmth of her hand through my romper.

When the song is done, I hold the caterpillar out to her.

“You can hold on to it if you want. Until your mom gets here.”

She considers this, and then she reaches out and takes it, pulls on its head and tail until its plastic spine is stretched as far as it will go.

“An exoskeleton means your skeleton is outside of your skin,” she says.

I want her to keep talking. I like how her words appear sure and solid out of her mouth. As long as she’s okay, I’m okay. “What else do you know,” I ask, “about exoskeletons?”

But the girl is not listening to me; she is watching someone walk across the lawn, a woman with red hair in black slacks and a blazer, sunglasses covering her face. “Mom,” the girl calls. Her voice shrill and sharp like a siren, cutting through the noise. “Mom!” And a dozen heads turn instantly. “Mom,” she yells again. The woman does not hear her.

The girl starts to run across the grass field, the caterpillar a green blur in her hand. And now the woman in sunglasses sees her and cries out and starts running too, and when they meet, the woman falls down to her knees, almost knocks the little girl over, makes sounds that have no words. The other parents look away, look down. One woman plugs her ears.

“Mom mom mom mom.” The girl says. “Mom mom mom.”

Whatever was keeping her calm all these hours is gone, and she is crying, and the two of them fit together perfectly, hands to lips, cheek to hair. They exist together in a universe, just the two of them.

I turn to Taylor.

She’s gone.

I turn in a full circle. Where did she go?

And then I see her. Her back is to me, but I know it’s her; her yellow shirt shining like a tiny sun. She’s standing with a group of parents, by a side entrance to the building. The door warped and hanging off its hinges. Through the open doorway, I can see a dark hallway covered in debris, shadowed and narrow like a cave underground. The man who was yelling earlier is saying something to Taylor. He has the door propped open and he’s holding a flashlight. He’s not wearing his helmet any more. “There’s too much rubble to go through,” he says. “The space is small, less than two feet. You’re gonna have to crawl.”

When she turns around, I see that she is holding the man’s helmet.

Oh no no no no.

“They need someone small,” she says. Her eyes are dark and calm. If Taylor goes into that building, she is never coming out. This I know, don’t ask me how. I know I just know.

“She’s still alive,” she says. “I can feel it.” And the tears run towards her mouth and rest in the curves there and she does not wipe them away.

How do I explain to her that I have nobody else? That if she goes inside that school, I will be standing alone in a field.

But that red-haired girl with her mother. How they fit together, body into body. The sun catching the red shine of their hair.

Taylor puts her forehead against my forehead, just like earlier, and I feel her body shaking and we say nothing because there is nothing else to say. She puts the helmet on her head and clicks the straps together under her chin.

The man who gave her the helmet leans down and says something in her ear, and she nods. Then she turns and walks through the doorway. The circle of parents move silently to let her pass through. I watch her until I can’t see her anymore, her yellow shirt fading into the dark hallway as if into the mouth of a great and terrible beast.