A Portland Public Schools initiative to bring students living in outer East Portland back to schools in North and Northeast saw almost no applications this academic year.

PPS’s Right to Return transfer program is modeled after a similar housing program administered by the city of Portland, which invites families to move back into areas where they once lived before high prices drove them out. (Most of the families are people of color, but the program does not select applicants based on race.) In 2023, after years of work with Black community leaders, PPS developed a plan of its own to work with David Douglas, Reynolds and Parkrose school districts to allow students to come back to 19 of its schools.

In its first year, the program struggled to gain traction, with 24 applicants of whom 23 students were accepted (one was denied for lack of space). In its second year, this academic year, the numbers were even lower. Just six students applied for Right to Return, and two were turned away for lack of space.

That’s a total of 27 students accepted over two school years. According to a district memo from Judy Brennan, PPS’s enrollment director, one student has since graduated and four have unenrolled, meaning 22 students currently enroll in the program.

That’s far fewer students than the district projected attracting. Back in 2023, WW reported, the district anticipated 50 to 100 kids would apply that year. This time around, district representatives did not offer comment.

Ron Herndon, executive director of Albina Head Start and a longtime Portland education advocate, says the program’s low numbers don’t surprise him at all. Since Black leaders first conceptualized the program in 2017, Herndon says the pandemic, turnover in district leadership, and the teachers’ strike all hindered movement on the project.

“I don’t think there’s been a sustained effort to implement the policy,” he says. “There’s no effort. It’s lucky that six people are aware of it.”

The news about Right to Return’s declining numbers comes as the district faces steeply declining enrollment, which is contributing in part to a projected $40 million budget deficit for the upcoming 2025-26 school year.

Valerie Feder, a district spokeswoman, said in March that the district would launch a Recruitment, Retention and Recovery enrollment campaign, a “data-driven effort” to build family trust and bolster enrollment. “We’re focused on areas with the most significant declines, using marketing, outreach and engagement to bring families back,” Feder said.

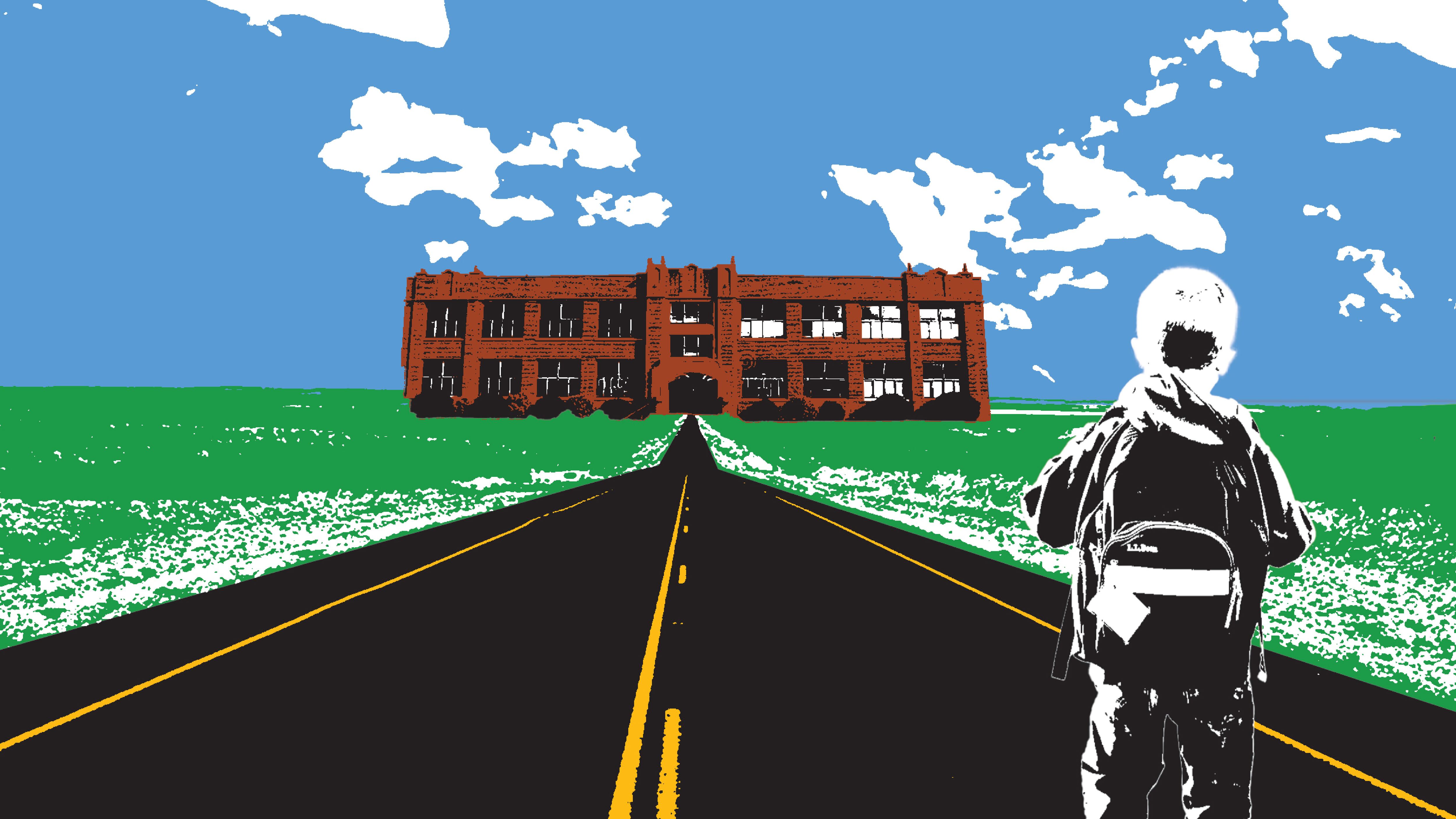

Boosting enrollment is especially important for one of the schools Right to Return targeted: Jefferson High School. The North Portland school, once the only majority-Black high school in Oregon, enrolls just 459 students. The district is planning to modernize the high school with $458 million to $466 million pooled from its 2020 bond and upcoming May 2025 bond.

Herndon says if district officials want to push forward with a new enrollment campaign, they must learn from the mistakes of Right to Return. He says he didn’t hear of sustained efforts to distribute flyers or raise awareness about the programming. For any enrollment campaign, Herndon says the district engage community partners and keep consistent tabs on the program.

“It requires concentrated effort; they need someone to be responsible for it,” Herndon says. “If it needs to be changed, then you do that. But that’s not going to happen unless you actually have somebody who is responsible for the effort.”